But hope persists that we can blunt the worst impacts, if not slow down the warming

Granted, it’s been a relatively cool summer in many parts of California. But state officials are saying, “Don’t get used to it.” How would you like to see the number of “extremely hot” days (105 or hotter) in Sacramento increase fivefold in the next few decades? That’s just one of many new projections from the state’s latest official climate assessment.

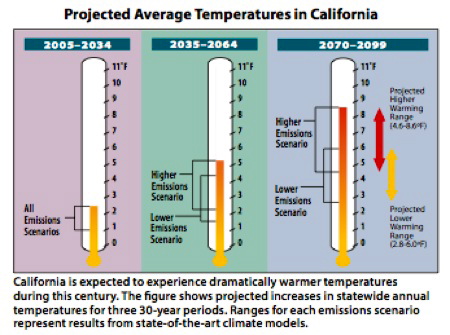

One hundred-twenty scientists worked on the report, entitled California’s Changing Climate (PDF). Funded by the California Energy Commission, it’s actually a portfolio of studies and contains some of the most specific warnings we’ve seen. For instance, it projects that going forward, average temperatures in the state will warm at three times last century’s pace. It’ll mean heat waves happening more often and lasting longer.

And there’s new evidence from a refined set of models that the state will be drying out. “By mid-century, already we’re seeing a drying trend which could be up to ten percent drier by the end of the century, says Susanne Moser, identified as the principal researcher for the report, “and that is significant for a lot of people.” Especially if you live in say, the San Joaquin Valley, where the report projects that the frequency of “dry years” could increase by about a third in the “latter half of this century,” compared to the late 20th century.

And authors expect the weird weather to get worse, projecting that as soon as 2050, what’s now considered a 100-year storm could become ‘an annual event.”

State officials nearly fell over each other to say that it’s not too late to blunt some of the worst effects, however, with astute planning and aggressive action to reduce global warming emissions. Ken Alex, who heads Governor Jerry Brown’s Office of Planning & Research, characterized the mounting climate threats as, “a series of plagues,” but added that, “we’re not helpless. We need to adapt and we need to understand what that adaptation requires.”

Some interesting numbers from the study:

- 1.7: increase in statewide average temp from 1895 to 2011, in degrees Fahrenheit

- 2.7: likely increase by 2050, compared to 2000

- 20: Number of days per year that the temp could reach 105 in Sacramento by 2050 (versus four, historically)

- 10-18: Likely range of additional sea rise along California by 2050 (v. 2000)

- 23: Number of San Francisco fire stations that would likely be inaccessible with 16 inches of additional sea rise (considered likely by 2050)

The study suggests that temperatures will rise more in the summer and inland, with springtime warming “particularly pronounced” and fewer cold nights. Farmers depend on chilly nights to produce some high-value crops, such as stone fruits. Officials at the Energy Commission expressed concern about potential impacts that rising temperatures will have on the state’s power grid, some of which we addressed in a previous post.

As for reducing emissions enough to make a tangible difference, Moser concedes that’s not a job that California can do alone. But she said this report is the first to target findings to the kinds of questions that officials and planners have been asking (like the aforementioned matter of how many triple-digit days they can expect–and how soon).

4 thoughts on “No Relief in Latest California Climate Assessment”

Comments are closed.

Craig, link for the report, California’s Changing Climate, in 2nd PP does not work. This seems to be correct:

http://www.energy.ca.gov/2012publications/CEC-500-2012-007/CEC-500-2012-007.pdf

Thanks, Wes. I was trying to circumvent the PDF link but they may have taken that other page down. I’ve replaced the original link with the PDF download.

I think it would interesting to compare the projections here with those used in the BDCP documents. It is not quite obvious, since they don’t use the same baseline and one talks of 2050 while the other talks of 2100. Hope I get the time to do this.

What was the “cutting-edge science” used to determine that California is threatened by global warming – Regional Climate Models?

• Studies from the third assessment used projections from six global climate models, all run with two emissions one lower (B1) and one higher (A2)

• Global modeling results were then “scaled down” using two different methods to obtain regional and local information.

However, there is growing evidence that down scaled models are useless.

Kevin E. Trenberth who leads the Climate Analysis Section at the USA National Center for Atmospheric Research wrote an essay in Nature entitled Predictions of climate In his essay, Trenberth wrote: “…..we do not have reliable or regional predictions of climate.”

Pielke Sr., R.A., and R.L. Wilby, in a paper on Regional climate downscaling – what’s the point? , Eos Forum, listed a set of reasons that regional downscaling of multi-decadal models are not skillful. . . “It is therefore inappropriate to present …. multi-decadal climate prediction….results to the impacts community as reflecting more than a subset of possible future climate risks.”

Dr Pielke summarizes an number of peer reviewed studies in a post on his blog Climate Science and concludes that Kevin Trenberth, on the issue of regional down scaling, is correct.

“The significance is that multi-decadal regional impact studies, based on predictions of changes in climate statistics, are not only a waste of time and money, but are misleading policymakers.”

Today we have the Third Assessment Report for California policy makers that uses useless models to drive the mitigation of California warming that is not happening and cannot be effectively predicted in the future. A clear waste of our tax dollars by a state that is broke.