California’s Yosemite National Park has been scarred by several big fires in recent years—the latest contained less than two months ago. But new research affirms that this crown jewel among national parks is likely to have even more fire in its future.

In late August, when fire crews attacked the Big Meadow Fire in Yosemite, it was hard to blame nature for the 74-hundred acres lost. That was a “prescribed burn” that got out of hand (or “escaped,” as the official report puts it). But nine out of ten wildland fires in the Sierra start with a lightning strike. Newly published work suggests that as California’s climate changes, the combination of warmer temperatures, less snow and more lightning strikes could mean 20% more fires by mid-century.

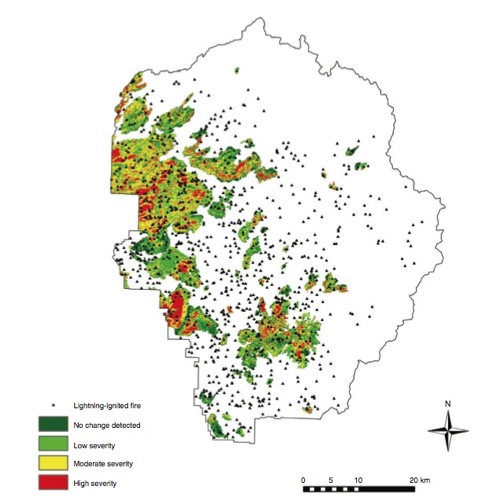

USGS research forester emeritus Jan van Wagtendonk co-authored the study with James Lutz at the University of Washington. He says they studied 20 years of Yosemite fire data to identify a trend. The mechanism starts with the oft-cited warming scenario, causing more rain and less snow at upper elevations.

“What happens in the mountains is that, as snow recedes in the spring the moisture in the fuels follows,” says van Wagtendonk. “The fuel starts drying out earlier and we extend the fire season by having more days available for fires to burn.”

But there’s another wildcard in the deck: lightning. Separate studies suggest that higher concentrations of atmospheric carbon dioxide will set the stage for more lightning strikes.

The study assumes a 17% reduction in snowpack by 2050—under the relatively modest B1 warming scenario, drawn from IPCC models. The results are in line with other climate studies that imply not just more fires, but more intense fires as the climate warms. It’s a trend, says van Wagtendonk, that has already started:

“We were able to trace, through satellite imagery, the change that we’ve seen in the severity of those fires just over the past 20 years, so it’s been obvious to us from those data that whatever temperature trends are occurring today are already having an effect on increased severity.”

“We see more of the same,” said the forester, “and a continued increase in both size, number and severity of fires.”

Scott Stephens, an associate professor of fire science at UC Berkeley, says lightning is changing the landscape in more ways than one.

Stephens recently told KQED’s Central Valley Bureau Chief, Sasha Khokha: “In Yosemite and Sequoia-Kings Canyon, they manage quite a few lighting fires in the wilderness area, away from people, and they allow these things to burn for months and months and months to try to allow that lighting fire to begin to shape the landscape again like it did 100 or 200 yrs ago. Those types of events probably increased the resiliency of the forest to deal with climate change and other impacts.”

The article is published in the current issue (10/27) of the International Journal of Wildland Fire.

KQED’s Central Valley Bureau Chief, Sasha Khokha, contributed to this post, as well as to the radio report.