How many gallons to run that microwave?

We hear a lot about how green our energy is in California. Instead of using coal, the state runs on natural gas and increasingly, renewable power.

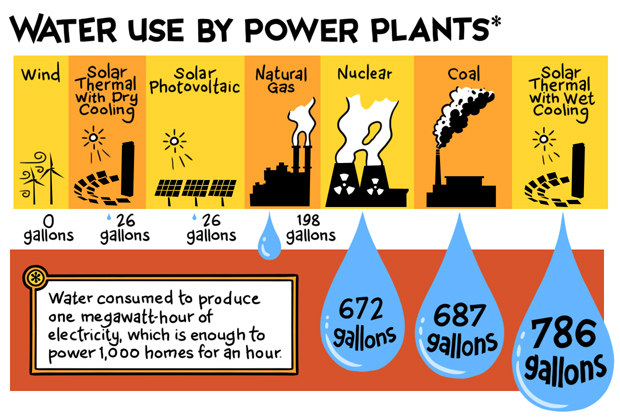

But there’s a hidden cost to our energy supply: water use. In fact, every time you turn on a light, it’s like turning on your faucet. It’s been calculated that it takes 1.5 gallons of water to run a 100-watt light bulb for 10 hours.

The way water and power work together is a lot like a tea kettle. Steam drives the power industry.

How Power Needs Water

You can see it at the Gateway Generating Station, a natural gas power plant in the northeast Bay Area. The plant looks complicated but making power is pretty simple. Step number one: burn natural gas. That produces a lot of heat.

“You’ve got 1,700-degree exhaust energy, or waste heat,” says Steve Royall of PG&E, who is giving me a tour through the maze of pipes and compartments. The heat hits pipes that are filled with water and the water is boiled off to create steam. That’s step number two: make steam to turn a steam turbine, which is attached to a generator. It’s the water that’s making the power.

But water has another job in power plants. That steam, even after it makes power, is still hot. So, most power plants use water to cool it down. “You’ve got to have the ability to cool everything down so the cycle can continue and your equipment doesn’t overheat,” says Royall. (Learn more about how power needs water in this illustration).

Nuclear plants and coals plants use water the same way, in some cases, millions of gallons a year. In fact, nationwide, power plants need more freshwater than farms do, according to a U.S. Geological Survey study.

Newer power plants reuse water, but a lot of it is lost to evaporation, which means it has to be replenished. “Typically water has been the most abundant resource available,” says Royall, “but as water resources become more valuable, it’s extremely important that we think about water use.”

Future of Water Scarcity

“There is a general understanding that the era of abundance is over,” agrees Heather Cooley of the Pacific Institute, an Oakland-based think tank focused on water issues.

“Water resources are limited and there is a growing demand. We have growing population in the West. We have a growing economy.”

And then there’s the climate – which is changing. “The climate models suggest that water availability will be more variable. So we’ll have wetter years, we’ll have drier years. We’ll have a smaller snowpack,” says Cooley. In some places, power plants are already feeling the effects of tightening water supplies.

[module align=”right” width=”half” type=”aside”]

Power plants can “chill out” in various ways:

Once-Through Cooling

California’s nuclear plants and some natural gas plants guzzle huge volumes of ocean water for cooling, more than 2 trillion gallons of water in 2010. The water is released back into the ocean but at a much higher temperature. This method is being phased out in California due to concerns about the impact on marine life.

Wet (Recirculating) Cooling

These power plants use water for cooling, recirculating it multiple times. But once the cooling water gets hot, it’s cooled back down through evaporation. In 2010, California power plants consumed more than 63 billion gallons of water this way.

Dry Cooling

Instead of using water for cooling, dry cooled plants use huge fans to blow air over the pipes of hot steam. This method uses very little water, but it uses more energy, creates higher emissions and is costlier to install.

[/module]”We’re seeing in areas where, if there is a drought, where plants are either forced to curtail their generation or turn off completely. And we’re seeing plants that are not being built because of concern about the long-term availability of water supply,” Cooley says.

Power plants can cut their water impact by using recycled water. “We can look at less water-intensive renewable energy systems. So looking at wind and at solar panels,” says Cooley.

But it turns out, some renewables need water, too.

Solar Technology Grapples with Water Costs

In a parched corner of California’s Mojave Desert, construction equipment shimmers in the mid-day heat. These 3,500 acres near the Nevada border are the site of the Ivanpah Solar Project.

“The Ivanpah project, when it’s operational, will be the largest solar thermal project operating in the world,” says Joseph Desmond with BrightSource Energy.

You’ll notice he said “solar thermal,” a technology that’s different than the solar panels you see on rooftops. The plant is a huge field of mirrors that are specially angled to focus the sun’s heat at a tower, 400 feet tall.

“Inside the top of that tower is a boiler. All of the energy is then is used to create high temperature, high pressure steam in excess of 1,000 degrees Fahrenheit,” says Desmond.

That spins a steam turbine that makes electricity. Just like a natural gas plant, that steam has to be cooled back down, which is normally done with water. In the desert, it’s not easy to find. “You have to dig down, I want to say about 840 feet,” says Desmond.

So, the Ivanpah plant will use a new technology called “dry cooling.” Instead of using water, the plant uses massive fans to blow air over the pipes of hot steam. “Air cooling allows us to reduce the water consumption by as much as 90%,” says Desmond.

But there’s a catch. Dry cooling uses more energy, so the plant’s not as efficient. It’s even less efficient when it’s hot out.

It also costs more to build. “It can range between one and five percent more. Now, that may not seem like a lot but when you’re competing and every penny counts, it’s an important factor,” Desmond says.

Three of the seven solar thermal plants planned in California won’t use dry cooling. But Desmond says, even though the state needs renewable power, he doesn’t think agencies would approve that today. “I think it’s safe to say if somebody said we’d like to use water cooling, that getting a permit for that would be challenging to say the least.”

The same could be true for fossil fuel plants, too, as California’s future water supply is called into question more and more.

Explore the Water and Power series and hear Lauren’s radio story on KQED’s The California Report.

Explore the Water and Power series and hear Lauren’s radio story on KQED’s The California Report.

One thought on “The Water That Fuels California’s Power Grid”

Comments are closed.

climate change might increase the inefficiency of this plane if temp is important.