Pacific ocean conditions that often portend a dry winter sure haven’t so far.

Scientists like to joke that “climate is what you expect, weather is what you get.” The relatively soggy winter so far is a classic example of that.

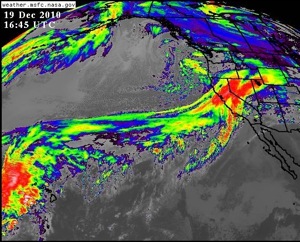

A closely-watched oscillation in the Pacific is in the La Niña phase this winter, creating colder-than-normal surface temperatures and distorting weather patterns. Usually a La Niña means drier-than-normal conditions for Southern California in particular and often for northern parts of the state as well. Not this year–at least not so far. The rain set multiple records over the weekend. Los Angeles has had a third of its average annual rainfall in a week. So what’s going on?

Kevin Trenberth, who heads the Climate Analysis Section at the Nat’l Center for Atmospheric Research, says lately there’s a monkey wrench in the works, in the form of a “blocking anticyclone.”

“In La Niña conditions, which is what we have now, the main storms that come into North America come barreling into Washington, Oregon and British Columbia more,” Trenberth told me in a phone interview.

But lately a persistent region of high pressure in the north Pacific is diverting storms south, into California. Trenberth says: “There’s a crapshoot or a random component to it, if you like, in the more northern latitudes, that’s adding some extra flavor to what’s going on, I think.

But that doesn’t mean it’ll keep raining. The tap could be shut off at any time and Trenberth, for one, still thinks it’ll happen. He says this is considered a “strong” La Niña and is still likely to wield influence over the winter as a whole. One clue is ocean temperatures in the central-to-eastern Pacific, which are running 2 degrees C (3.5 F) below normal. “That only occurs—probably less than 10% of the time, so it’s a relatively rare event and certainly stronger than anything we’ve seen in recent years,” said Trenberth.

Earlier in the season, Jet Propulsion Laboratory climatologist Bill Patzert told the Los Angeles Times that 82% of La Niñas since 1949 have produced below-average rainfall.

That’s more the case for the Southland. As you move north, La Niña’s influence on precipitation reverses itself and the Pacific Northwest gets doused. Trenberth says the transition line is right about 40 degrees north latitude. Around that line, La Niña’s effects become murky and things can go either way. San Francisco is at 37 degrees north and Reno is at 39.

6 thoughts on “So Much for La Niña”

Comments are closed.

The Farmer’s Almanac predicted a wet winter…

Ha! Well, there you go. Stick with a trusted source.

I may have been the reporter who interviewed Patzert for the Times. In fairness to Patzert, he said that La Ninas produced lower rainfall in the southwest; he was clear about their ability to intensify rainfall in the northwest. If I didn’t dwell on it, it’s because I wasn’t writing for readers in Washington and Oregon. The moveable nature of the La Nina influence is a tricky thing for western water managers to parse: if the wet belt during a La Nina year extends south far enough to include the part of the Sierra that feeds the Sacramento and San Joaquin rivers, then La Ninas could contribute to what in part is a good water year for So Cal’s importation systems. But La Nina takes away by often leaving the Rockies feeding the Colorado River watershed low. We get a lot of water from there, too. I feel for Patzert on this one; he has an unmatched and brave record calling dry years – he was the first to insist the Colorado River was entering long term drought – and he’s taken a lot of flak from it western water managers who just didn’t want to hear what he had to say. I’m glad your piece stresses that a Pineapple Express pushed over So Cal doesn’t negate the dominant influences of La Nina. I wish that these generous rains weren’t also so easily misconstrued and capable of gulling Southern Californians into a false sense of water security. Thanks for the good post. -EG

Thanks, Emily. It was indeed your piece, which I’ve now linked from my post. The north-south split in the effects of El Nino and La Nina are a widely misunderstood-but-important part of the story.

For those interested, Emily’s blog is at:

http://chanceofrain.com/

“I wish that these generous rains weren’t also so easily misconstrued and capable of gulling Southern Californians into a false sense of water security. Thanks for the good post. -EG”

Do you mean to write “lulling” or did you intend to insult your audience by labeling them as foolish and gullible?

Only Emily can say what she intended, but for my money gulling is the right term. To begin, I don’t think the word is as harsh as you seem to. I see the word akin to deceive, with the added element that the victim of deception is less than careful (foolish, perhaps, but the dictionaries also use the softer term unwary). Anyway, the public is gullible and not very knowledgeable on matters of climate and weather.