Industry looks for inroads in a “stalled” California market

One of California’s two nuclear power plants remains offline amid roiling speculation about its future. At a geothermal energy conference in Sacramento this week, the head of California’s Independent Energy Producers association put the odds of the San Onofre Nuclear Generating Station (SONGS) “ever” coming back online at 50/50.

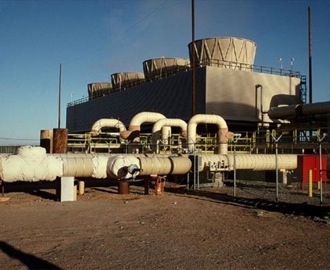

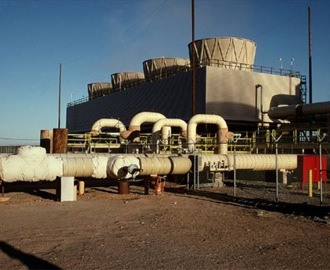

The odds matter because nuclear plants provide so-called “baseload” power, which is to say that they produce electricity 24/7 — when they’re on. Geothermal power — tapping energy from underground sources of heat — also has the virtue of being baseload. While geothermal plants can lose potency during the hottest part of the day, they don’t stop producing completely. Solar and wind are considered “intermittent” sources as they’re at the mercy of the sun shining and wind blowing.

At this week’s meeting of the Geothermal Energy Association, there was visible consternation over geothermal being the odd man out in California’s race for renewables, even though the Golden State is endowed with the most geothermal capacity in the nation.

“There’s no question that the geothermal industry is stalled in California,” lamented Karl Gawell, GEA’s executive director. The question of the day was how to turn that around. Several speakers suggested that geothermal developers seize on the current uncertainties around California’s nuclear future as an opening to tout the advantages of geothermal’s always-on potential. Obstacles include a potential dearth of transmission lines to carry power from typically remote geothermal sites and technicalities in state policies that tend to favor wind and solar development. By contrast, geothermal development is surging ahead in Nevada.

Money is another potential stumbling block. Geothermal requires drilling deep wells at upwards of $5 million per. Californians currently get about five percent of their electricity from geothermal sites. But that’s changing rapidly and the state is on track to get the lion’s share of renewable energy from the sun and the breeze. The reliance on intermittent sources for all that power has more than a few insiders worried.

“When we look at the 2016-17 time frame and see thousands more megawatts of [intermittent sources] coming online…our eyes get really big,” said Karen Edson, a vice president at California’s Indpendent System Operator (CAISO), the switchyard for electricity throughout the state. “We’re very worried about that.”

[module align=”left” width=”half” type=”pull-quote”]”The more [renewables] we put on the system, the more it matters how it all fits together.”[/module]

Mixing more intermittent sources into the state’s energy mix makes “load balancing” a trickier proposition for grid managers. As energy guru V. John White of the Center for Energy Efficiency & Renewable Technologies put it, “The more [renewables] we put on the system, the more it matters how it all fits together.”

Geothermal has its detractors. UC Berkeley Physicist Richard Muller, author of Energy for Future Presidents, insists that it will never be cheap enough to compete.

“Compare geothermal to solar,” Muller told me in a recent interview. “The energy coming from below is three thousand times smaller than the energy coming from solar. I mean, it’s as competitive as solar if you can make it three thousand times cheaper.”

Still, there’s a lot of potential juice down there. Government reports estimate that with the right technology, drillers could recover power equivalent to more than half the nation’s current installed base.

“The biggest risk right up front is finding the resource,” says Doug Hollett, at the federal Department of Energy. Hollet says his Geothermal Technology Program is aggressively seeking “game-changing” advances that will lower the financial risks by speeding up the drilling process or underground imaging techniques to identify where the “hot rocks” are.

But geothermal won’t provide an immediate answer for San Diego. Edson describes San Onofre as, “a bit of an odd beast,” serving an area that’s relatively isolated in terms of electrical power. “It’s not something that increased imports can solve.” The plant’s operators are currently filling the power gap by ramping up the half-century-old gas-fired plant at Huntington Beach. But getting adequate renewable energy in to replace the lost low-carbon electrons from the nuclear plant, officials admit, will be a challenge.

2 thoughts on “Nuclear Woes Could Create a Window for Geothermal Energy”

Comments are closed.

Muller was so wrong for so long on climate change. Now he seems to be pushing natural gas. I wouldn’t put too much stock in his naysaying about geothermal.

At this week’s conference of the Geothermal power Energy Organization, there was noticeable consternation over geothermal being the odd man out in California’s competition for renewables, even though the Fantastic Condition is gifted with the most geothermal potential in the country.

happy retirement