Nearly 3,000 tons of spent nuclear fuel have accumulated at nuclear power plants in California…with nowhere to take it.

It could be worse. This could be Illinois, the undisputed spent fuel champ, with more than 8,000 tons piled up at plants. As it is, California ranks eighth in the nation.

“This country has an obligation to those states and those communities to take those materials and put them into deep geologic disposal, where they can be safely isolated for a very long period of time,” says Per Peterson, who chairs the nuclear engineering department at UC Berkeley.

Trouble is, the country seems farther now from meeting that obligation than it was in 1998, the original legislative deadline for opening a permanent repository for spent nuclear fuel.

Peterson is also member of a White House commission on nuclear waste solutions, due to report its findings next Friday. Between now and then, Climate Watch and KQED’s The California Report will collaborate on a three-part series on the issue of high-level nuclear waste.

“We’ve made progress but it’s taken an enormous amount of time,” Peterson told The California Report’s Senior Producer Ingrid Becker, in a recent interview.

The Blue Ribbon Commission on America’s Nuclear Future is not expected to offer specific site recommendations for long-term storage. More likely, it will suggest an interim strategy of sort-of-long-term storage for the 65,000 tons of accumulated waste sitting more or less literally in the back yards and “attics” of US plants.

Peterson thinks a good place to start is with the spent fuel still sitting in dry storage at two decommissioned plants in California:

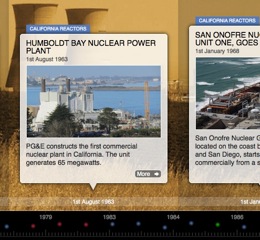

– Humboldt Bay, the state’s first commercial nuclear plant, which went online in 1963 (160 tons), and

– Rancho Seco, east of Stockton, which Sacramento voters shut down by referendum in 1989 (202 tons)

Peterson suggests consolidating the “relatively modest amounts” of fuel from those locations somewhere that can serve as a pilot project for “informing decisions as to what do with the spent fuel of larger quantities at Diablo Canyon and San Onofre” (California’s two operating plants). Peterson says that “getting to the development” of a permanent tomb for spent fuel “conceivably could happen in 20 to 30 years.” From some estimates we’ve seen, that’s at the optimistic end of the timeline.

Speaking of timelines, you can explore the history of commercial nuclear power in California, with our interactive timeline, assembled by Chris Penalosa.

Speaking of timelines, you can explore the history of commercial nuclear power in California, with our interactive timeline, assembled by Chris Penalosa.

Experts agree that most vulnerable to both terrorist attack and natural disaster are the uranium fuel rods suspended in pools of water at reactor sites. Utilities operating Diablo Canyon and San Onofre have both begun moving older, less radioactive rods to more durable “dry casks.” The bad news is that two-thirds of California’s spent fuel remains in “wet pools.”

The good news is that Gregory Jaczko, chairman of the federal Nuclear Regulatory Commission, told a Senate hearing that he believes the temporary storage methods used in this country are adequate for the next 100 years or so. Let’s hope he’s right because at this rate, it might take that long to find a permanent home.

Where the Waste Resides

This interactive map shows the current locations and amounts of spent nuclear fuel at commercial reactor sites in California.

View California Nuclear Power Plants in a larger map

Tune in to the companion radio series: Part 1: California’s nuclear waste profile. Part 2 (Tue): What we can learn from Sweden. Part 3 (Wed): The town that said: “Yes, in our back yard.”