Abnormally warm summer temperatures were felt across much of interior California

By Nicholas Christen and Craig Miller

Autumn is here, so says the calendar. Living on the coast, it might be easy to think that California escaped the heat wave suffered by much of the nation this summer. While that may be true for most of the large coastal population centers, it was a different story for much of the state’s interior farm belt.

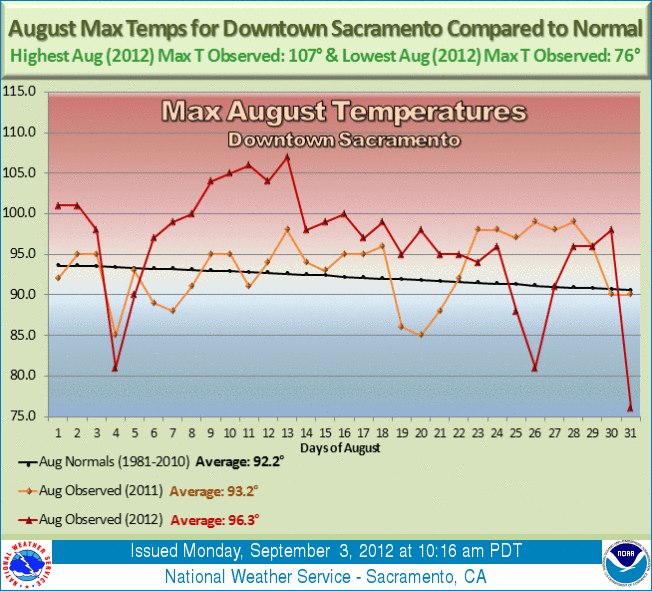

Throughout June and July, even Central Valley spots escaped much of the heat felt by the Great Plains, though Cal Expo officials blamed the heat, in part, for tamping down attendance at the state fair. Then things heated up quickly — especially in the Sacramento and San Joaquin Valleys — through August and into September. Valley towns including Redding, Red Bluff, Sacramento, Merced, Madera, Fresno, and Bakersfield, have been on the order of three-to-five degrees above normal for the duration of August and September.

[module align=”right” width=”half” type=”aside”]

Some of the most extreme deviations in August average temperatures:

- Merced +5.1

- Fresno +4.8

- Bakersfield +4.6

- Sacramento: +4.1

- Madera +3.0

[/module]

Fresno saw 27 days above normal during August and most of those days were at least three degrees above normal, a string one meteorologist at the National Weather Service in Fresno called, “pretty amazing.”

Even Central Valley farmers, who are used to triple-digit days, were taken aback.

“Yeah, this summer has been one of the hottest that I remember,” said Don Cameron, who runs 7,000 acres of crops for the Terranova Ranch, southeast of Fresno. He’s been farming the Valley for 30 years.

“Our tomatoes have taken a little bit of a beating from the 110 degree weather we’ve had, but with the drip irrigation we’re able to keep them a little fresher, a little cooler when it does get hot like that.”

On the day we visited Cameron, the fever seemed to have broken. “Yeah, we’re in the low 90s today,” he snorted. “It’s like — like a spring day.”

“We had just a couple of weeks on end where we were 109, 110, 111 degrees. Just brutal. The nights don’t cool down, it’s hard on the plants, it’s hard on the people.

There has been a plus side to all this.

“I can remember we used to get a lot of real severe frosts during the spring growing season,” recalled Cameron. “I can’t remember the last time we had one that was actually a killing frost during April.” That’s created an opportunity of sorts for growers. “We’ve been able to plant our tomatoes earlier in the year for earlier harvest, which extends the, the season for the cannery.”

The roast continued well into September, bringing with it an unusual late-season streak of 90-plus-degree days in downtown Sacramento. This year could eclipse the September record of 20 days, set back in 1899.

See more on how climate change is challenging California farmers on the documentary, Heat and Harvest. It premieres Friday evening on KQED TV.

4 thoughts on “California’s Farm Belt Didn’t Dodge the Summer Heat Wave”

Comments are closed.

The heat wave also meant sky high electric bills for many Californians. The longer growing season, didn’t seem to translate into much cheaper prices at the grocery stores, though. Not that I noticed at least.

Californians must adapt a holistic overhaul of our poiicy and practice for energy, environment and economy. Obviously, the current path does not improve the environment at all, meanwhile bankrupting California both at state and city levels in government, economy, education and science/technology. All theses green energy policy and practice appear never to reduce the energy cost and support the economic development in California with little benefit for improving environment.

If taking a holistic approach, Californian should put the bio energy in the center for everything we plan for our economy development and environment cleanup (a new concept, not only environment protection but cleanup).

For example, there is a maturing, revolutionary technology, called microwave plasma gasification, which is capable to ionize any organic wastes such as municipal waste and forest biomass into basic element status and convert carbon and hydrogen compounds into syngas for biofuel and electricity production with 80% net energy output and zero emission and pollution. In the process, the technology can also recover 60% of metals such iron and allummina.

In addition, if allowing the private sectors to cover 1/4 or more California desert area with reforestation, harvest the biomass wastes from all state forest parks and private lands and retrieve all municipal landfills as feedstocks for biofuel and syngas production, these alone sequester all greenhouse gas emission by whole USA power plants and automobiles and graduately eliminate the municipal landfill’s pollution in underground water and in air as well. Also this technology can reduce the cost of all industrial toxic wastes with much better outcome of environment benefits.

As continuing, there are two additional parts in the holistic approach I previously suggested, one is to utilize the drip irrigation system for agriculture and reforestation to improve the efficiency of water resources by 90%. Another is to utilize the reverse osmosis technology to desalination of sea water for both residents and industries, using wind and solar power along the coastline.

In policy and regulation making, state government should privatize the maintenance and management of public forests and commonditize the biomass for biofuel feedstocks as economic incentives.

As estimated, all accumulated municipal wastes and landfills would be enough to generate the biofuel and electricity for all Californians to drive and house utility for at least five years. If 1/4 California desert area covered with industrialized reforestation (forests healthy by proper irrigation and regular thinning), the resulted biomass harvests would be enough to support the same energy production in five years. Besides, this approach almost eliminates the huge properties and lives loss caused by wildfire and firefighting cost every year and the huge air and soil pollution as well.