There are still many questions about bird migration, including how it’s affected by climate

Millions of birds make their way through the San Francisco Bay Area on the way north to their breeding grounds every spring. Many shorebirds and waterfowl have already left, and now waves of songbirds are passing through. As well-watched as birds are, there are still a lot of things scientists don’t know about migration, including precisely where different species go each summer and winter, and what exactly triggers them to get going. Since so many birds pass through here, the Bay Area is a good place to try and sort out some of the questions, and to try to tackle another: how does climate change affect birds?

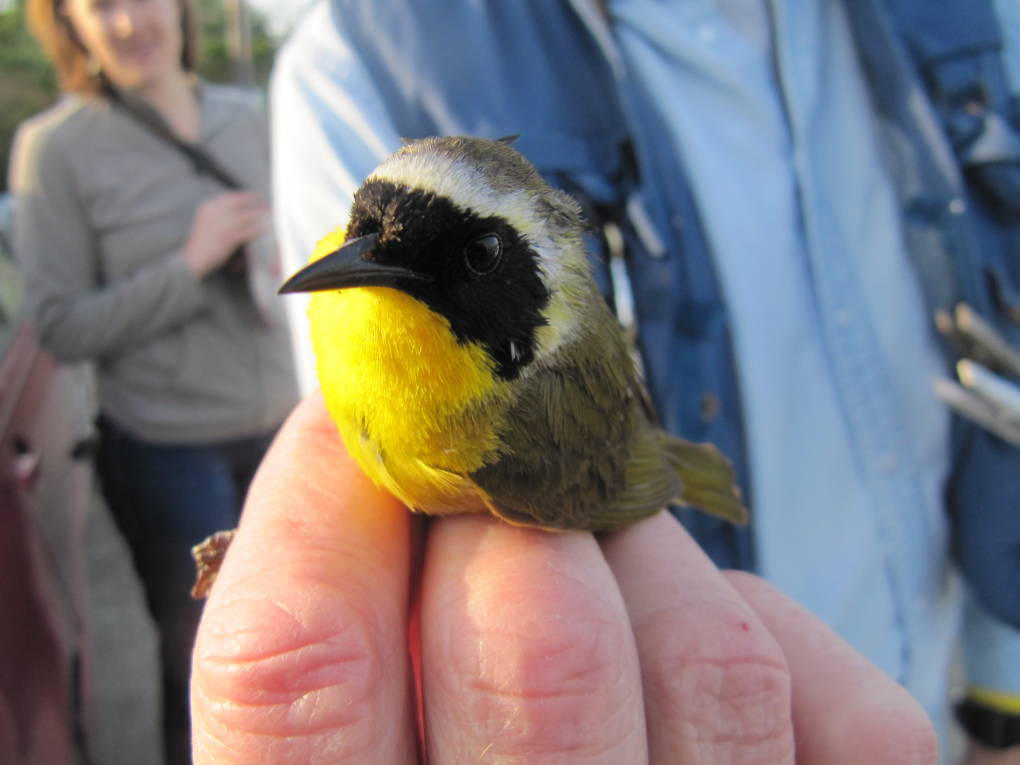

The San Francisco Bay Bird Observatory, a non-profit science and conservation organization, has been monitoring birds here for 30 years. The information collected through its bird banding program, has helped reveal some of the likely effects of climate change on birds. For example, a paper released last year suggests that climate change is making some species larger.

[module align=”right” width=”half” type=”pull-quote”]“With anything biological, it’s never as simple as we’d like to think it is.”[/module]

Another study, yet to be published, finds that in the past two decades, migration has changed for some species, but not always in the same way. Two species, the Swainson’s thrush and yellow warbler, are arriving in the Bay Area earlier in the spring, while the orange-crowned warbler, yellow warbler and Pacific-slope flycatcher are arriving later in the fall. The Wilson’s warbler migrates over a longer period of time in the fall, while in the spring, the orange-crowned warbler migrates over a longer duration, and the Wilson’s warbler and Pacific-slope flycatcher migrate for a shorter duration.

“With anything biological, it’s never as simple as we’d like to think it is,” Gina Barton, who did the study as a grad student at Kansas State University, told me over the phone. She said while her study points to these changes happening, she can’t gauge what kind of effect they’ll have. “It’s really hard to tease apart what’s going on,” she said. “It could be very drastic for populations if the timing of arrival isn’t coinciding with food during migration, for instance,”

If populations of birds do begin to change more drastically, the volunteers and staff at the Bird Observatory will probably notice. They catch and band birds three days a week, all year long. They have hundreds of thousands of records, dating back thirty years.