Could be second-driest winter on record for California, Pacific Northwest

Last week’s State of the Climate report issued by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration found that this winter is stacking up as the warmest since 2000 and the fourth warmest on record in the contiguous United States.

According to NOAA, 47 of 48 states experienced above-average temperatures in the period between December and February, with the greatest increases seen in the Northeast and Midwest.

Only New Mexico saw below-average temperatures.

In spite of the Bay Area’s balmy winter, California’s average temperatures during the three-month span were only slightly above average — and .2 degrees Fahrenheit cooler than last year during the same period.

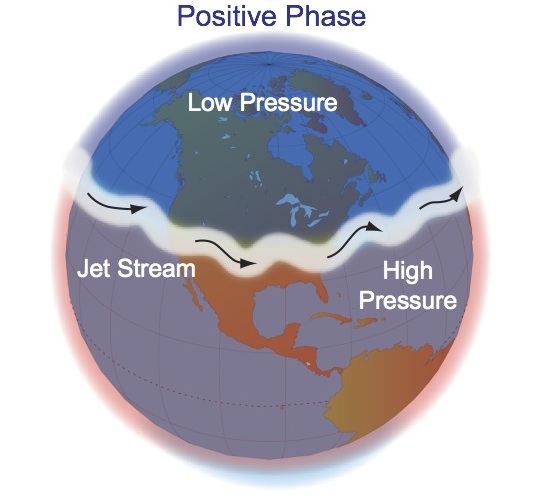

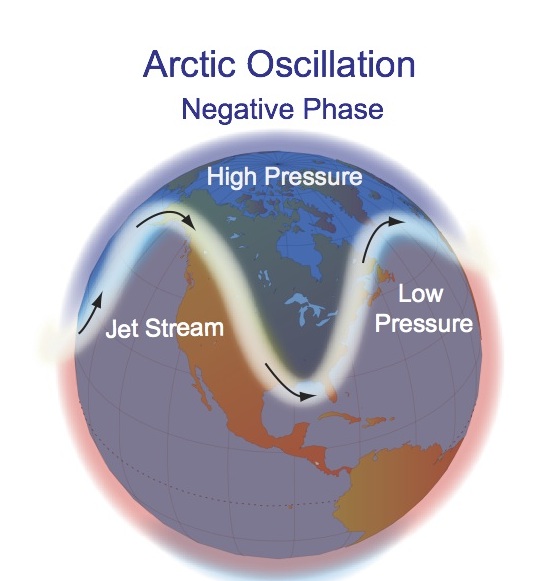

Deke Arndt, chief of NOAA’s Climate Monitoring Branch, said the nation’s warmer weather is partly attributable to a phenomenon known as the Arctic Oscillation, or AO, which is a determinant in how far north or south the jet stream will be situated. “This year’s index was ‘positive’ for most of the winter,” Arndt told me. “This is an indicator that the jet stream will stay further north.”

Arndt compared the influence of the Arctic Oscillation to playing with a jump rope. The more positive the index, he said, the more the rope is pulled taut. “There is a stronger pressure gradient between the mid and upper latitudes, which means that the jet stream tends to get ‘locked’ further north and cold air from the arctic does not penetrate as far into the interior of North America.” Conversely, Arndt said, last year’s wild winter can be partly attributed to a “negative phase” of the oscillation, he said, which contributes to greater variability in the latitude of the jet stream and increased likelihood of arctic air being drawn over the continental U.S.

Arndt noted, however, that there is a complex set of factors at play in determining temperature including this winter’s ocean conditions in the Pacific — known as La Niña — and feedbacks from long-term warming. “Rarely does a single factor dominate all results in all places,” he said.

Kelly Redmond, a climatologist with the Western Regional Climate Center, cautioned against extrapolating too much from the data. “From winter to winter, the warm areas tend to move around a bit,” Redmond wrote. “With La Niña we tend to see cool and wet/snowy conditions along the northern tier states and warmer, drier conditions along the southern tier.”

The last three months have not merely been warm but dry, particularly in the Pacific Northwest and California, which, according the report, is in the grip of its second driest recorded winter. “Storms coming onto the West Coast have either been shunted north, or torn apart before reaching California,” wrote Redmond. “We look to be in a respectable wet pattern later this week. Maybe the wettest episode of the winter for the northern half of the state and mountains.”

One study cited in the NOAA report, published by the Rutgers Global Snow Lab, pointed out that the area of snow cover across the U.S. was the third smallest it’s been in 46 years of satellite data.

According to the report, a full 39% of the country was in the midst of a drought. However, the percentage classified as D4 or “exceptional” drought shrunk, from 3.2 to 2.5%, largely the result of a spate of recent wet weather in Texas and the Southern Plains.

Overall, 2011 was the 11th warmest year globally since record-keeping began in 1880.