Midwest outbreak is the worst in U.S. history — and may be a sign of things to come

William Reisen began studying tropical diseases when he was drafted in the Vietnam War. He’d studied insects in school, so he worked as an entomologist for the Air Force. Eventually, his career led him to California, where he now heads UC Davis’s Center for Vectorborne Diseases. But even with his professional experience with mosquito-borne diseases, he says he never expected to see West Nile virus in the United States.

“Everybody was surprised,” he says. “If you were a betting person, and you wanted to guess the next virus that would cause trouble from abroad in North America, I think few of us would have expected West Nile.”

West Nile, a disease carried by birds and spread by mosquitoes, first made inroads in the U.S. in 1999, in New York. By 2003, it had reached California. In 2004 and 2005, there were hundreds of human cases; in those two years combined, 48 people in California died.

[module align=”left” width=”half” type=”pull-quote”]”A lot of folks have forgotten what it’s like to have mosquito-borne diseases.”[/module]

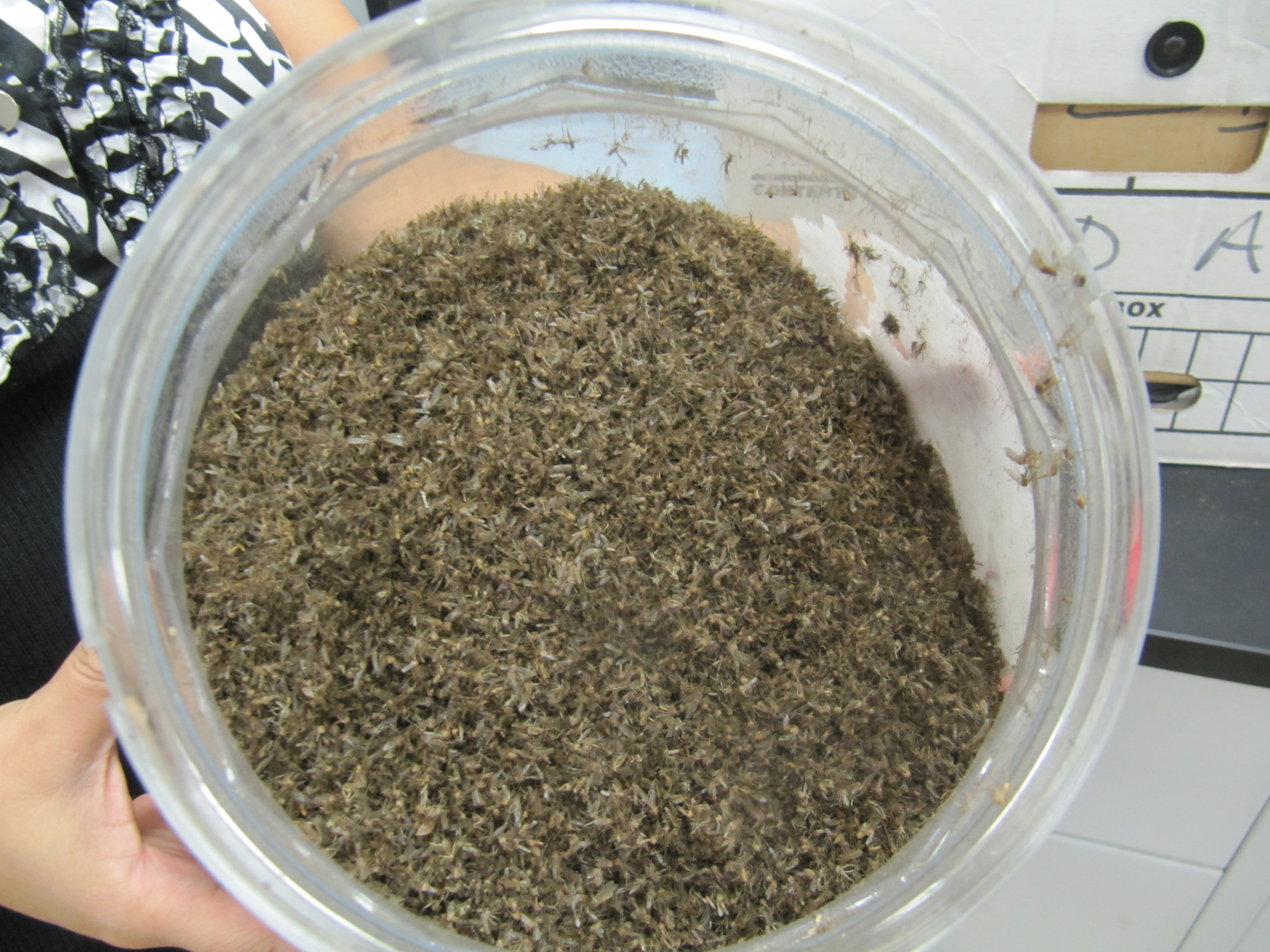

As I report in a story for The California Report on Wednesday, Reisen’s lab at Davis is a crucial cog in California’s West Nile Virus surveillance program. He and his team test thousands of mosquitoes and dead birds for the virus, and work with the California Department of Public Health and mosquito control districts around the state to track where the virus is flaring up.

Reisen’s not only interested in where the virus is now, though. He’s also looking to the future, and that means factoring in climate change. The mosquitoes that transmit West Nile thrive in hot and dry conditions. Temperature is especially important, since the warmer it is, the faster mosquitoes reproduce. They bite more frequently and the virus itself can replicate and spread more quickly (I unpack the details in the radio story; you can also read about them on this Scientific American blog post).

With temperatures likely to rise in California — and not only in the places that are already hot, but according to new research, on the coast, too — that’s good news for mosquitoes and the West Nile pathogen, bad news for people.

“It’s not a fun thing to get,” Reisen says. “It’s easy for epidemiologists to count numbers, but if it’s your grandmother in the hospital with a swollen brain and not recognizing you when you come to visit, it’s a totally different take-home message.”

Reisen still seems almost awed by West Nile’s success in North America.

“If you had to think of a Ugandan virus taking up shop someplace, certainly Saskatchewan wouldn’t be the first place you’d look,” he says, referring to recent outbreaks on the Canadian plains. “We never would have suspected that it would have successfully spread now from Canada to Argentina and from ocean to ocean.”

As the climate gets warmer, temperate regions will become friendlier to mosquitoes and tropical diseases. West Nile virus is not the only one to watch out for. Reisen rattles off a few others he’s worried could gain a toe hold in North America: Rift Valley fever, Japanese encephalitis, Chikungunya virus. Other scientists have expressed concern about Dengue fever. Malaria could begin to make inroads.

Vector-borne disease isn’t new to California. Malaria used to occur here. St. Louis encephalitis and western equine encephalomyelitis are both native insect-borne diseases. So the state has experience with mosquito control. California’s network of mosquito control districts dates back to 1917.

“We’ve had pretty good public health measures for many years,” says David Brown, the manager

of the Sacramento-Yolo Mosquito and Vector Control District. “I think a lot of folks have forgotten what it’s like to have mosquito-borne diseases from when your parents or grandparents had to deal with it.”

Brown’s district is one of the largest in the state, and he and his staff take a multi-pronged approach to mosquito control. They run education programs, encouraging people to get rid of standing water around their homes, whether it’s in a neglected birdbath, an old can or a roof gutter. They use pesticides to kill mosquito larvae and adult mosquitoes. They distribute mosquito-eating fish (for free; somewhere around 1.2 million fish a year) for people to put in ponds and unused swimming pools.

“To be a really good, comprehensive mosquito control program, it’s not a one and out,” Brown says. “A lot of folks think, well, we’ll just take care of the problem and then it’ll go away and we won’t have to worry about it again.” But Brown says with climate change looming, it’s as important as ever to keep up the combination of mosquito monitoring and mosquito control.

Reisen has some concern that that’s not enough. His lab can turn around West Nile results in 24 hours. But West Nile is all they’re looking for.

“A good surveillance project should cast a broader net.” He says the state should be preparing to test for the other viruses that could appear here. Viruses and mosquitoes can hitch rides on airplanes and travel to new hemispheres overnight. As the world gets warmer, they’re able to survive and spread, too.