Documents include details on depth and location of wells in California

[POST UPDATED, 4/3, 5:04pm]

It’s no secret that with several recent years of drought, California’s groundwater supplies have come under increasing strain. But Dennis O’Connor, a water consultant with the State Senate Natural Resources and Water committee, wants to rewrite an arcane piece of California water law that, for decades, has kept documents containing information on the state’s groundwater resources under wraps.

The documents O’Connor wants released to the public are called well completion reports, or “well logs” – technical documents filed by well drillers with the state. Under California water law, well logs are confidential, accessible only by individuals in state agencies or those who meet special criteria.

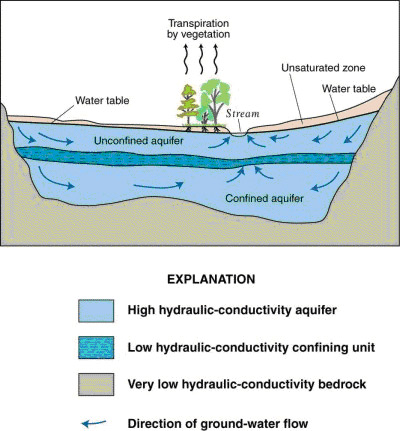

“These logs are rich sources of information. The data can help you connect the dots and create a three-dimensional picture of what’s going on underground,” O’Connor told me. Logs contain data on the depth, location and geology of the sites as well as engineering details such as the kind of casing used and the angle of drilling.

The information, says O’Connor, would be highly useful to hydrologists looking to map aquifers and study historical trends in the state’s groundwater supplies – the kind of macro-level understanding of groundwater that he says is lacking across the state. “You need to know the physical characteristics of a basin in order to effectively manage it,” said O’Connor.

[module align=”left” width=”half” type=”pull-quote”]While groundwater accounts for 30-to-40% of the state’s total water supplies, California has no statewide groundwater management plan.[/module]

California is the only state in the western U.S. that does not make its well logs available to the public. In states such as Oregon, Idaho and Utah, well log reports are accessible in searchable online databases.

O’Connor’s push for greater transparency seems to fall in line with a 2009 amendment to the state water code, which requires the Department of Water Resources (DWR) to begin monitoring seasonal and long-term trends in groundwater elevations across the state. According to Mary Scruggs, a DWR senior engineering geologist, the information contained in well logs is not always comprehensive but can be a critical asset in understanding long-term changes in the state’s groundwater basins.

With the extremely dry weather in recent years, aquifers throughout California have been drawn down rapidly. In an average year, according to the Department of Water Resources, California’s groundwater is overdrawn by 1.4 million acre-feet, a volume greater than what is used in an average year by all the residents in the San Francisco Bay Area. A 2009 NASA satellite study found that during a period of prolonged drought between 2003 and 2009, overdraft was as much as 4.4 million acre feet per year – more than three times the average annual overdraft reported by the DWR.

While groundwater accounts for 30-to-40% of the state’s total water supplies, California has no statewide groundwater management plan. Groundwater basins are managed instead through local ordinances, joint management plans – known as GWMPs — and, when conflicts between water users arise, through the courts. There are currently 22 “adjudicated basins” across the state, most of which are in southern California.

O’Connor has been working with state senator and Natural Resources and Water committee chair Fran Pavley, a Democrat who represents sections of Los Angeles and Ventura Counties, to draft legislation that would make logs for all new wells (or those modified, abandoned or destroyed after ratification) publicly available.

The bill, SB 1146, is currently in committee and is a modified version of a SB 263, a bill vetoed earlier this month by governor Jerry Brown. (In a subsequent memo [PDF], Brown wrote that well logs should be made public but that the proposed penalties under SB 263 were too severe.)

A key concern among opponents of last year’s bill was security of public drinking water. The San Gabriel Valley Water Association, a volunteer group of stakeholders in southern California, said confidentiality of well logs was necessary to “protect water supplies and facilities from sabotage and attack.” Others said the bill could expose well drillers to increased risk of lawsuits.

While investor-owned water agencies are presently concerned with security, O’Connor says the confidentiality of well logs has historically benefited private entities, in particular private well drilling companies, looking to maintain “proprietary” control over local groundwater resources.

“The incremental risks of this bill are as close to zero as you will find,” he said.

One thought on “New Bill Would Make Confidential Groundwater Info Public”

Comments are closed.

If you want a clue as to the truth of any statement, follow the money. In the case of California Water, that is the only rule you need.