US power plants are “stressing” freshwater supplies, finds science watchdog group

For the second time in as many weeks, a major report has emerged warning of consequences from the demand that America’s electricity producers are placing on water supplies.

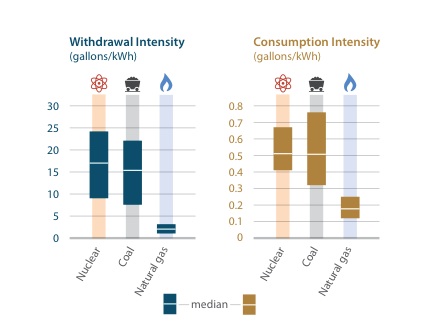

Today’s findings, from the Union of Concerned Scientists, conclude that water and power are on a collision course in the US, as nearly all major power plants slurp up water for cooling. As of 2008, the UCS study found that across the US, “thermocooled” power plants (which is most of them) took up somewhere between 60 billion and 170 billion gallons of water from rivers, lakes and aquifers. That’s three times the volume of water that pours over Niagara Falls. At least 2.8 billion and as much as 5.9 billion gallons of that was “consumed,” or not put back.

“It’s really water that keeps the lights on,” says Kristen Averyt, deputy director of the Western Water Assessment at the University of Colorado, and lead researcher for the report.

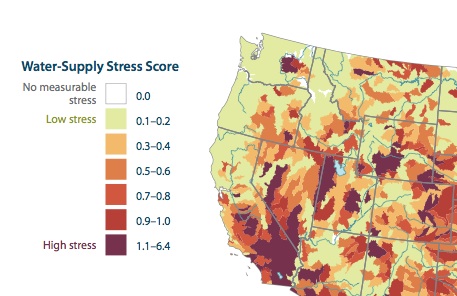

Coal, natural gas and nuclear plants — even some solar power plants — produce electricity by generating steam to power turbines (90% of the nation’s electricity is produced in this way), and require “vast volumes” of water for cooling. The authors say this, in turn, is putting stress on watersheds around the country.

The good news is that California and Western plants tend to be less water-intensive than elsewhere in the nation, though the authors say that among Texas plants, nearly half the water used comes from underground aquifers. Here in California, many major power plants are located along the coast and use seawater. But all plants have one thing in common: they tend to put back the water much warmer than when they withdrew it.

“Fish can’t climb out of the hot tub,” says Rob Jackson, who studied the effects on water temperature from plant cooling for the UCS report. Jackson says that despite bans by several states on putting back water hotter than 90 degrees Fahrenheit, eleven of those states have power plants exceeding the limit. Jackson cited one plant in Florida, which was found to be returning water to the Manatee River at 115 degrees, literally Jacuzzi temperature.

The report also points to “significant gaps and errors” in industry figures that purportedly track water use by power plants.

The UCS authors singled out one California solar plant as a paragon of water-efficient design. The Ivanpah thermal-solar array, under construction by Oakland-based Brightsource Energy, will use a “dry-cooling” system. That seems prudent, as it’s located in the middle of the desert.