This post was contributed by Andrew Freedman of our content partners at Climate Central. Find out why scientists are using volcanoes as a possible model for global climate intervention, on the Climate Watch blog and on KQED’s Forum program.

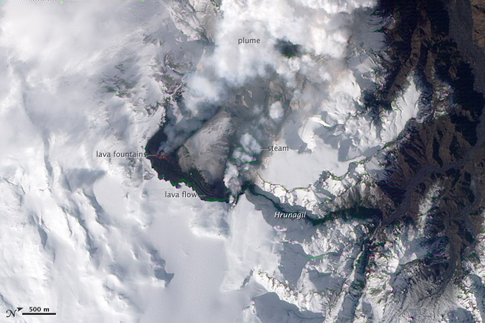

The ongoing eruption of Mt. Eyjafjallajokull in Iceland is disrupting flights across Europe, shutting down some of the busiest airports and aviation corridors in the world. But could it also disrupt the climate system, leading to a temporary cooling trend this summer?

Not likely, according to Rutgers University environmental sciences professor Alan Robock, an expert on how volcanoes alter the composition of the Earth’s atmosphere. According to Robock, the Icelandic eruption hasn’t contributed enough sulfur dioxide to the upper atmosphere to significantly alter the climate.

“From what I’ve seen from the observations so far, there hasn’t been enough put into the atmosphere to have a large climate effect,” he said in a telephone interview.

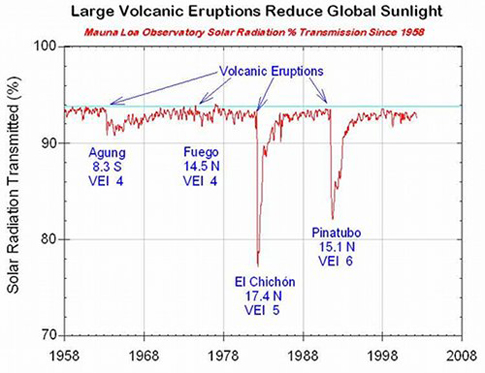

It is well known that volcanic eruptions can affect the climate. Just ask historians, who can tell you about the “year without a summer” that followed the enormous eruption of Mt. Tambora in Indonesia in 1816. More recently, the 1991 eruption of Mt. Pinatubo in the Philippines, which contributed about 20 megatons of volcanic material to the atmosphere, cooled global average surface temperatures by about one degree Fahrenheit in the year following the eruption.

By vaulting particles of sulfur dioxide and other reflective aerosols high into the stratosphere, volcanic eruptions can reduce the amount of solar radiation reaching the planet’s surface. However, this only results in temporary cooling, since chemical processes and air currents remove the particles over time.

In addition to causing short-term cooling, volcanoes also contribute carbon dioxide (CO2) to the atmosphere, which in the very long-term balances slow CO2 losses from other causes. The volcanic contribution of CO2 to the atmosphere is estimated to be well less than the recent human contribution, on average.

Robock noted that the ash cloud that is canceling flights would not alter the climate, since it will fall out of the air in a matter of days. “What’s dangerous for airplanes is not what causes climate to change,” he said.

The volcano’s climate impacts may also be limited by its high-latitude location, since the air circulation in the upper atmosphere in the high latitudes tends to be more efficient at getting rid of volcanic material, compared to lower latitudes where sulfur dioxide particles from volcanoes can linger for years.

Robock noted that Icelandic eruptions have disrupted climate in the past, such as a long duration event in 1783-4 that cooled temperatures in Europe, catching then US ambassador to France Benjamin Franklin’s attention. According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Franklin was a pioneer in linking a volcanic eruption to climate change.

It’s still possible that this volcano, which is continuing to erupt, may yet send more volcanic material into the upper atmosphere, thereby causing a cooler summer in the northern hemisphere.

4 thoughts on “Icelandic Volcano Chills Travel Plans…But What About the Climate?”

Comments are closed.

Laki, volcano, 2,684 ft (818 m) high, S Iceland, at SW edge of the Vatnajokull glacier. Its eruption in 1783 was one of the more devastating on record, leading to the deaths of a quarter of Iceland’s inhabitants (mainly due to a famine that resulted from the eruption’s effects). Haze from the eruption spread over parts of Europe, where some experts believe it affected the inhabitants’ health.

Laki is also known for its atmospheric effects. The convective eruption column of Laki carried gases to altitudes of 15 km (10 miles). These gases formed aerosols that caused cooling in the Northern Hemisphere, possibly by as much as 1 degree C. This cooling is the largest such volcanic-induced event in historic time. In Iceland, the haze lead to the loss of most of the islands livestock (by eating fluorine contaminated grass), crop failure (by acid rain) and the death of 9,000 people, one-quarter of the human residents (by famine).

This event is rated as VEI6 on the Volcanic Explosivity Index, but the eight month emission of sulfuric aerosols resulted in one of the most important climatic and socially re percussive events of the last millennium.

In Great Britain, the summer of 1783 was known as the “sand-summer” due to ash fallout. The eruption continued until 7 February 1784. Grímsvotn volcano, from which the Laki fissure extends, was also erupting at the time from 1783 until 1785. The outpouring of gases, including an estimated 8 million tons of fluorine and estimated 120 million tons of sulfur dioxide gave rise to what has since become known as the “Laki haze” across Europe. This was the equivalent of three times the total annual European industrial output in 2006, and also equivalent to a Mount Pinatubo-1991 eruption every three days. This outpouring of sulfur dioxide during unusual weather conditions caused a thick haze to spread across western Europe, resulting in many thousands of deaths throughout 1783 and the winter of 1784.This disruption then led to a most severe winter in 1784, where an estimated to have caused 8,000 additional deaths in the UK. In the spring thaw, Germany and Central Europe then reported severe flood damage.

In North America, the winter of 1784 was the longest and one of the coldest on record. It was the longest period of below-zero temperatures in New England, the largest accumulation of snow in New Jersey, and the longest freezing over of Chesapeake Bay. There was ice skating in Charleston Harbor, a huge snowstorm hit the south, the Mississippi River froze at New Orleans, and there was ice in the Gulf of Mexico.

Combine these solar impact findings by Mike Lockwood, reported in the New Scientist, with the potential volcanic cooling and the folks in the UK and the European Continent are in for a cool summer and maybe a brutal winter.

“Mike Lockwood at the University of Reading in the UK began his investigation because these past two relatively cold British winters coincided with a lapse in the sun’s activity more profound than anything seen for a century. For most of 2008-9, sunspots virtually disappeared from the sun’s surface and the buffeting of Earth by the solar magnetic field dropped to record lows since measurements began, about 150 years ago.

Read these two sentences again:

“In addition to causing short-term cooling, volcanoes also contribute carbon dioxide (CO2) to the atmosphere, which in the very long-term balances slow CO2 losses from other causes. The volcanic contribution of CO2 to the atmosphere is estimated to be well less than the recent human contribution, on average.”

Ha!!! So Volcano=good since it replaces c02 from losses from other causes.

People=bad (based on “estimation, recent contribution, on average).

Yep, good old fashioned non-biased Journalism

You say “The ongoing eruption of Mt. Eyjafjallajokull in Iceland is disrupting flights across Europe,” but this is incorrect.

Notice in Russell Steele’s comment “the Vatnajokull glacier”, which is also incorrect usage, that Eyjafjallajokull and Vatnajokull both possess the “jokull” suffix.

This is because Jokull means glacier in the Icelandic language.

Likewise fjalla means mountain.

The correct usage would be “The ongoing eruption of Mt. Eyja in Iceland is disrupting flights across Europe, “