By Gretchen Weber & Molly Samuel

A companion radio piece to this post aired on The California Report.

Climate change is causing conservationists to rethink traditional methods of protecting lands and ecosystems. The conventional strategy of setting aside a specific parcel of land (and increasingly, ocean) to protect a particular community of organisms may no longer be sufficient in a rapidly changing climate. While greenhouse gas reduction and climate change mitigation remains a top priority for most conservationists, land managers have begun developing adaptation strategies that take the effects of a warming planet into account.

“We have a fantastic conservation success story in having conserved a huge network of protected areas,” says Healy Hamilton, director of the Center for Applied Biodiversity Informatics at the California Academy of Sciences. “The issue with those protected areas is that they all have static boundaries around them and they work to protect what lies within them, So the plants and animals that are there are well-protected, as long as they stay there.” Trouble is, the habitat isn’t staying put.

Climate has “Velocity”

The world’s ecosystems will need to move about a quarter of a mile each year to keep up with climate change, according to a recent study published in Nature (link is to the first paragraph of the paper; the full article is only available to subscribers, but you can read a press release about the about the study).

Researchers from the Carnegie Institution, Stanford, the California Academy of Sciences, and UC Berkeley collaborated on the paper, which describes climate belts sweeping north and south from the equator–and also moving uphill–as the world warms.

Hamilton, who co-authored the study, told a packed house at the Center for Biological Diversity in January, that “Climates are on the move. It’s not just a slow unfolding, it’s a radical, abnormal process. Everywhere we look, shifts are already occurring.”

And under these changing conditions, she said, plants and animals have three choices: “They can stay and adapt, they can shift with their climate, or they can go locally extinct if they can’t move fast enough.”

The study’s lead author, Scott Loarie, a fellow at the Carnegie Institution, explains that climate change forecasts are commonly measured in degrees per year, but the authors of this study wanted to know how those temperature changes would affect what can live where. So they used temperature “velocity” (in kilometers per year) to measure how fast regional climate conditions are moving as the planet heats up.

It turns out that the belts move at different rates, depending on the landscape. In the Amazon Basin, velocity is relatively high. It’s a large and homogeneous ecosystem, so as the temperature changes there, plants and animals will have to travel a long way to keep up with the climate in which they’ve evolved to thrive. In a place like California, with its microclimates and variable topography, the velocity is lower. Some species may need merely to migrate to a nearby north-facing–and therefore cooler–slope. Others will have to head north and toward the coast. Climate models forecast that eventually the Bay Area will look more like Southern California, and the Bay Area’s current climate will be located somewhere north of us.

Mapping a Moving Climate

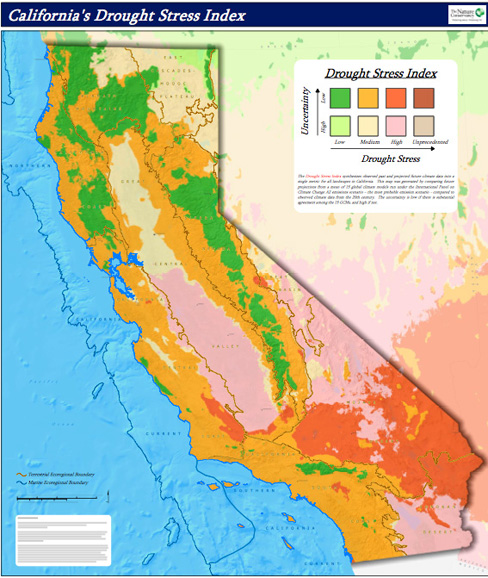

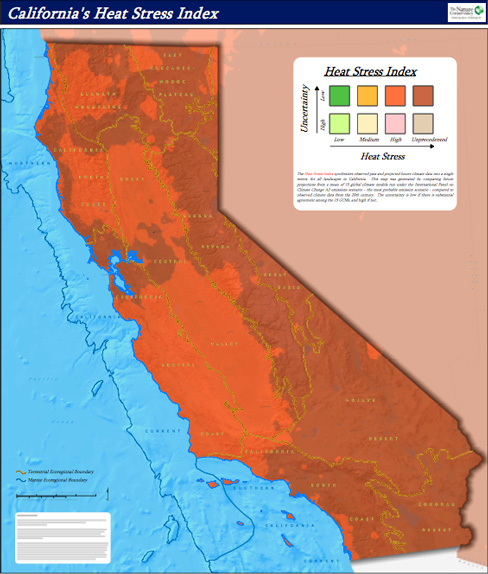

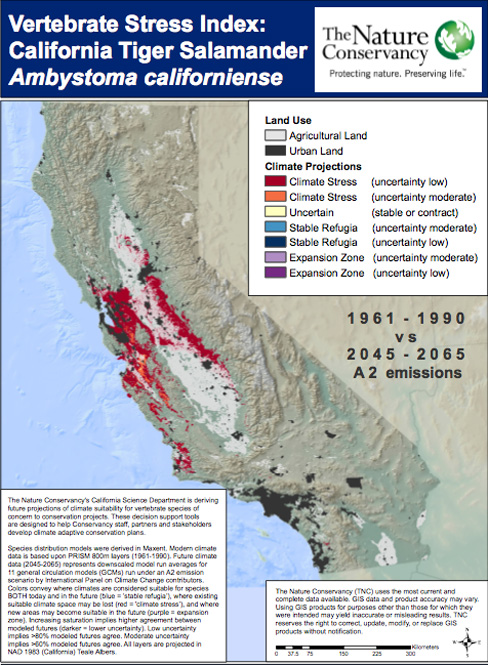

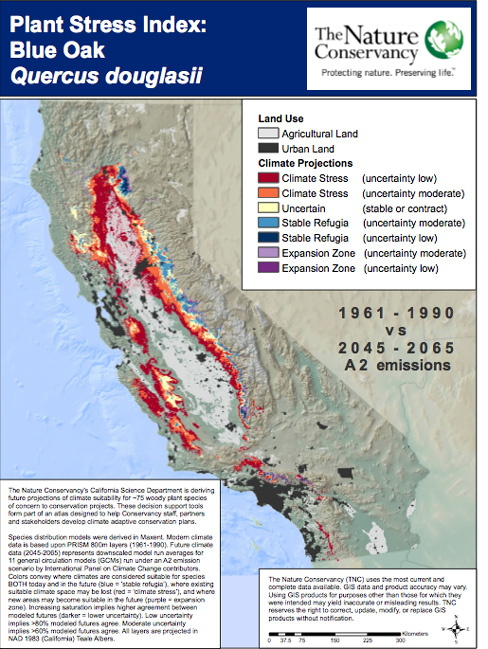

The Nature Conservancy of California has attempted to map some of these trends (see above and below). Scientists averaged together several different climate models to create a picture of California’s future in terms of temperature and precipitation. They then applied that projection to habitats for specific species, to make predictions about how ranges may shift. The maps show both how much areas are likely to change, as well as how certain the predictions are.

“What we’re trying to understand is how does the way we protect species in the future need to change with a changing climate,” says Rebecca Shaw, Director of Conservation for the Nature Conservancy of California. “The kind of strategies you employ and how much you spend is really going to be dependent on how certain you are about change in the future.”

For example, she says some parts of the Sierra are not likely to change very much over the next century, but some places like the Mojave Desert are expected to change a great deal. That kind of information could be useful for land managers trying to plan for the future. For example, in areas that are expected to undergo great change, it might be more important to preserve corridors, or connecting stretches of protected lands, so that populations can move as the climate changes, if they are unable to adapt where they are.

Loarie says “assisted migration”–helping specific species move to new locations–is expensive, unpredictable, and unrealistic. Instead, he, too, corridors for plants and animals to safely follow their climate–if they can keep up. Species like the American pika, already living on mountaintops, can’t go any farther uphill. Their habitats could disappear completely, or, as Loarie says, “they’ll pop off the top.”

There are limitations to the predictions one can make with temperature velocity measurements. What temperature changes will do to fog, for instance, is still unknown, so it’s not clear yet where the redwoods will need to move in the next 100 or so years.

To enable the second option, Hamilton agrees with Loarie. she says the conservation community needs to rethink its traditional strategy of protecting lands. Instead of protecting specific parcels of land and expecting them the stay the same over time, conservationists need to expect change, and to create connectivity in the landscape so that species can move when and if they need to.

4 thoughts on “Mapping California’s Shifting Climate”

Comments are closed.

Yet again, another use of unproven climate models to projected drought conditions for 2070-2100. What the ….

“The Nature Conservancy of California has attempted to map some of these trends (see above and below). Scientists averaged together several different climate models to create a picture of California’s future in terms of temperature and precipitation. They then applied that projection to habitats for specific species, to make predictions about how ranges may shift. The maps show both how much areas are likely to change, as well as how certain the predictions are.”

First you have to accept the notion that the climate is warming. As the hoaxers at the CRU admitted, no significant global warming for the last 15 years. None of the climate model predicted that change, just the opposite they forecast warming. If the models cannot forecast 15 years in to the future how can they project the climate in 2070-2100? Really?

Gosh, I hope the Natural Conservancy did not use any tax dollars to conduct this study! I hope we are not going spending taxes to implement this environmental daydream.

I cannot believe the audacity of humans. It is no longer a question of to play God or not, it is how. An endless moral balancing act between any human mental abstraction. You can argue thousands of facts, opinions, issues of money, motives, etc. Things that do not exist in reality of life, the life cycle that the planet knows. We have forgotten that we are only animals too sharing this planet. The sooner there are less humans the better off everyone will be.

We have the lead author for the IPCC and the father of the paper that the Nature Conservancy bases their projections upon, saying there has been no statisticly significant warming since 1995. So their projections are bogus. But even if we were to take this at face value.

Why do you assume that hypothetic warming in the future will cause drought when the modest, real world, warming of the 80’s and 90’s produced two of the wettest decades in Calif history?

Some people just have waaayyy tooo much time on their hands