Researchers hope to sway Congress on expanding the California-based standard, though it remains untested at home

Proponents of California’s low-carbon fuel standard (LCFS) hope problems with the federal Renewable Fuel Standard (RFS) could spell an opportunity to promote the state’s groundbreaking alternative approach at the national level.

Scientists from six research institutions—including UC Davis—are attending a bipartisan briefing on Capitol Hill this week to present the results of a new study touting the potential benefits of a national low-carbon standard.

LCFS — part of California’s AB 32 climate change legislation — calls for a 10% reduction in the “carbon intensity” (CI) of transportation fuels in California by 2020. The federal Renewable Fuels Standard (RFS), by contrast, calls for a gradual increase of 35 billion gallons of biofuel by 2022. It also establishes threshold production levels for various biofuel feedstocks, which is where it has run into trouble.

Corn-based ethanol, conceived as a temporary solution, continues to exceed the maximum production level set by the mandate. Meanwhile, production of cellulosic biofuels, derived from non-food and potentially more environmentally sustainable feedstocks such as grasses and wood chips, has fallen short each of the last five years. The EPA reduced the 2011 cellulosic biofuels mandate by a staggering 97%, from 250 million gallons to just 6.6 million.

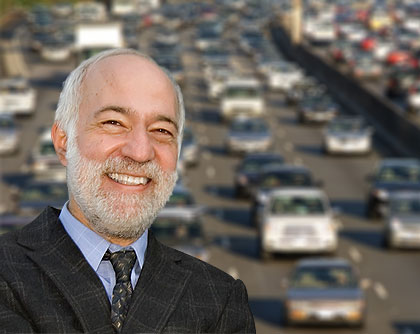

Daniel Sperling, director of the Institute for Transportation Studies at UC Davis and lead author of the study, sees an opportunity here. In the last six months, “the circumstances have changed a lot,” says Sperling. “People are curious whether [the California low-carbon fuel standard] could solve the RFS problem,” he says.

California’s LCFS includes all transportation fuels — electricity, natural gas, and hydrogen — as well as biofuels. It also gives fuel providers many more options to reduce carbon intensity, including:

- Reducing the CI of fuels they provide by selling more low-carbon fuels;

- Improving refinery and oil-field efficiencies;

- Capturing and sequestering carbon;

- Purchasing credits from other producers and fuel suppliers who are able to supply low-carbon fuels at lower prices.

Sperling says that the LCFS is intentionally designed to spur innovation by establishing regulatory targets that companies can bank on. But taking it national would require buy-in from corn farmers, advanced biofuels producers, electric utilities plus the automobile and oil industries, he adds. No easy task.