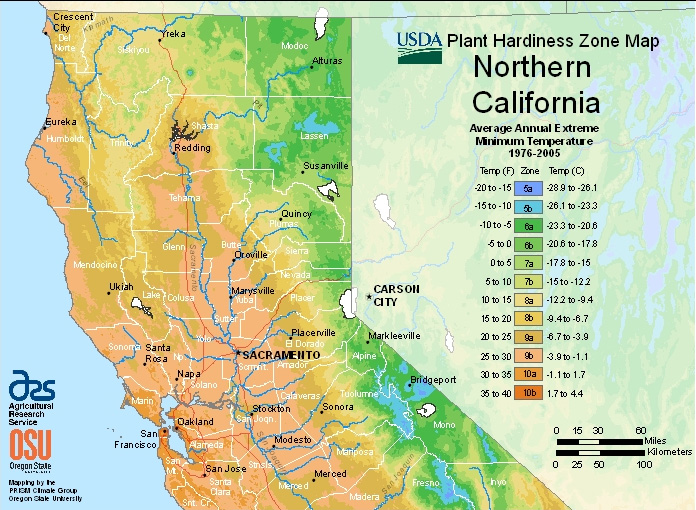

The USDA updates its plant hardiness map to 21st century standards

It’s been more than two decades since the U.S. Department of Agriculture updated its Plant Hardiness Zones Map, used by gardeners across the country to determine what will grow in their yards. The new GIS-enabled map unveiled this week is a boost to people who live in places that get a lot of cold weather and may be seeing slightly warmer average winters now. But in California, Sunset’s western zones guide has always been the gardener’s bible.

Kim Kaplan, a spokesperson for the USDA’s in-house research service stopped short of conceding that the revamped map was a nod to climate change. “In some cases you do see a warmer or colder zone, but there’s no way to ascribe that change just to the [30] new years of weather data we’ve added,” she told me, adding that the changes were driven more by updated technology. “The sophisticated algorithm that was created for how to draw the zones between where we have actual data points is something that was never done before” she said. Point taken. The new map shouldn’t be compared to the old map.

Various news accounts of the announcement have linked the warmer winters indicated in many areas to global warming trends. When I asked David Ackerly, a UC Berkeley biology professor about the disagreement he wrote in an email, “it is getting warmer and that will affect agriculture and gardening.” He takes the USDA’s point that the two official Plant Hardiness maps were created with different methodologies, but added that evidence of warming in cities is particularly important because those are the same calibration points for both maps. They aren’t subject to disclaimers about methods.

Despite the new level of detail in the map, gardeners in California and the Bay Area in particular, won’t learn much from it. “For the average person in a garden, this is a pretty crude estimate of what they could grow and what will grow around here,” said Paul Licht, Director of the UC Berkeley Botanical Garden. “I don’t think a lot of our plants are determined by how cold it gets for one hour at night.” That’s a reference to the map’s main data point, an average coldest temperature in a given place and time.

“We have incredible microclimates,” he told me. “Remember you can go from San Francisco as the crow flies 15 to 20 miles and the temperatures in the summer can be different by 30 degrees or more.” That kind of variation isn’t common in other parts of the country, although there are microclimates everywhere. “You really have to be part of your garden,” was Licht’s advice for Bay Area gardeners. Only the gardener really knows what grows best in his or her garden.