High-tech imaging helps Colorado researchers catch the wind

It isn’t enough to buy a slew of multi-megawatt turbines and stake them on a windy hillside. You have to know how the wind behaves, not only going into the turbine but the “wake” coming out the backside. Otherwise, you can get more windstorm than wattage. It’s a new area of research and it got help this week from scientists who literally “look” at the wind.

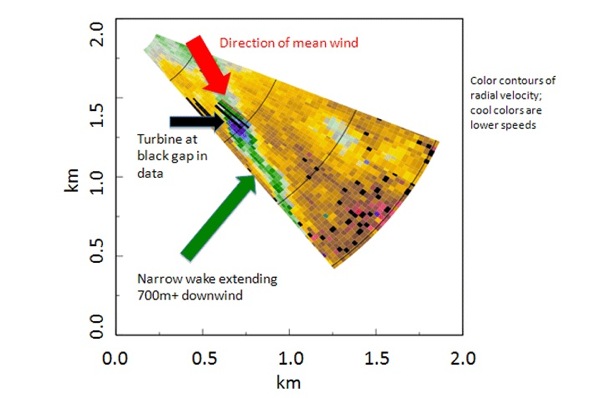

Speaking at the American Geophysical Union (#AGU11) here in San Francisco, Julie Lundquist from the University of Colorado, Boulder, offered up her team’s images of a wind turbine’s wake. Using Doppler Lidar — think police radar gun — she showed us the color-coded flow: a slower, cool-colored wake at the center just behind the turbine, surrounded by the warmer-colored fast flow swirling around it.

The first benefit from such information is turbine placement: too far away and you’ve got to buy or lease way too much real estate; too close together and you could damage your very expensive turbines (or reduce their output) with the very wind you’re hoping to harness.

“Most turbines are in the wake of another turbine, and most new wind farms are very large,” Lundquist told me, “so the information that we have can let the wind farm operators know how much power they’ll be producing because they can correctly account for wake effects.” Plus, if they know how much power they’re producing, Lundquist says they can bid more competitively on the open market which could eventually reduce the cost of energy.

A companion study that Lundquist touched on was intriguing for another reason. It’s already known that planting rows of trees near crops enhances the low-level turbulence in ways that help crops grow. For the same reasons, Lundquist says that crops close to a busy road are more mature in part because of the cars and trucks whooshing by — despite the exhaust fumes. Turbulence from wind turbines could work the same way: helping to speed up the heat exchange and cooling crops on hot days, even speeding up photosynthesis by boosting the CO2 exchange between plants and the atmosphere, she said.

And what’s the turbines’ effect on ground-level plants and animals, and birds overhead? In response to my question, Lundquist put out a call from the podium for collaborators on the next phase of their work You can find her at the National Wind Technology Center, just outside Boulder, CO.