A possible game changer in wind technology with an unlikely inspiration

Most of the wind turbines you see driving throughout the deserts and hill country of California look pretty much the same: soaring towers hundreds of feet high with massive, pinwheel-like structures on top, blades churning (or not) as the wind blows (or not).

But there’s another design for generating wind power that, if new research proves correct, could eventually become a far more common sight as California ramps up its portfolio of renewable energy. Vertical axis wind turbines look a little like upside-down egg beaters. They tend to be smaller than traditional turbines, and therefore less powerful. But according to John Dabiri, head of Caltech’s Biological Propulsion Lab, they can be far more efficient at generating power than traditional turbines are when they’re used together in just the right way.

Dabiri said the problem with standard turbines is that the turbulence or “wake” from the turning of one turbine disrupts airflow and reduces the performance of surrounding turbines. Locating them within 300 feet of each other can reduce performance by 20-50%, said Dabiri. That means standard wind farms need a lot of land.

Not so with his egg beaters, says Dabiri.

“With the vertical axis turbines, you can use the wake to your advantage by channeling the air through the wind farm,” he said.

To maximize the air flow, you have to position the turbines just right. And to determine exactly how to do that, Dabiri looked to nature.

“It’s identical to the problem with fish schooling,” he said.

Just as schooling fish work together to direct water flow for minimum energy expenditure, Dabiri said, wind turbines can be arranged to direct air flow for maximum energy capture.

Modeling his experimental wind farm after schooling fish was his starting point, he says, but since then he has discovered configurations that work even better.

In a recent paper based on his studies of six turbines at a two-acre test site north of Los Angeles, Dabiri argued that if you put the turbines in just the right spot relative to one-another, the efficiency and overall power output of wind farms can be increased dramatically. He found placing the turbines one diameter’s length away from one another increased performance 5-10%.

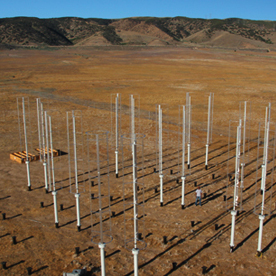

Dabiri has expanded his test site to 24 turbines and may build as many as 42. He says as he’s added more turbines to the study, his results are remaining constant, and he hopes to be able to apply his results and make projections for utility-scale wind farms within a year.

Dabiri says this is a new approach to answering the question of how to get more power from the wind. Traditionally, the focus has been on building taller, bigger, more powerful turbines, which come with costs of their own: negative environmental impacts on birds and bats, the need for lots of land, and higher price tags associated with expensive materials needed for building at such a large size. By focusing instead on the design of the wind farm itself, Dabiri said, it’s possible to capture more wind and produce more energy at lower costs with less environmental impact.