PG&E green program helps preserve forests already saved by state taxpayers

By Susanne Rust

California Watch

California’s largest utility company promises its customers green salvation through its ClimateSmart program.

For every bit of energy a PG&E ratepayer uses – turning on a vacuum cleaner, powering up a computer or heating up an oven – a little part of a tree or forest is saved to erase the carbon sins of the customer. The voluntary program costs ratepayers an average of $60 a year.

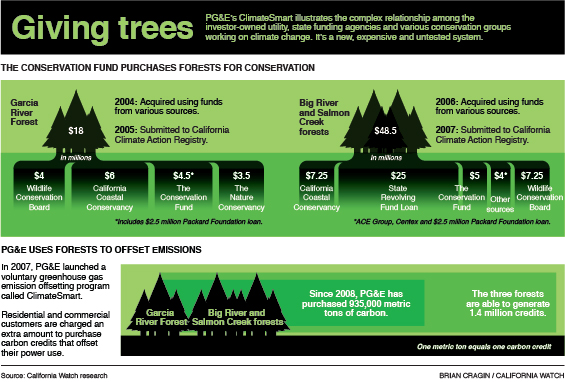

But the company isn’t telling its customers one crucial fact: Those forests were purchased years ago by a Virginia-based conservation group that used nearly $50 million in loans and grants from California taxpayers. That group, The Conservation Fund, then sold PG&E carbon credits on the land it had already purchased for preservation and selective logging.

But the company isn’t telling its customers one crucial fact: Those forests were purchased years ago by a Virginia-based conservation group that used nearly $50 million in loans and grants from California taxpayers. That group, The Conservation Fund, then sold PG&E carbon credits on the land it had already purchased for preservation and selective logging.

Thousands of PG&E customers are effectively paying twice for the same Mendocino County forests.

The ClimateSmart program highlights the complex and murky relationship among big business, state environmental regulators and various conservation groups working on climate change – a relatively new and untested system in which a vast amount of money is traded without much public scrutiny.

ClimateSmart, which has operated since May 2007, has more than 30,000 enrolled residential and business customers, including the American Lung Association and the beloved Bay Area coffee maker, Peet’s Coffee & Tea. Participants pay a surcharge based on their power usage.

ClimateSmart, which has operated since May 2007, has more than 30,000 enrolled residential and business customers, including the American Lung Association and the beloved Bay Area coffee maker, Peet’s Coffee & Tea. Participants pay a surcharge based on their power usage.

“We invest in these projects on behalf of our customers,” said Kathleen Romans, a spokeswoman for PG&E. “We’re procuring something for them. Their funds come to us, and we’re investing, under contract, projects that provide co-benefits – healthier habitat for wildlife, watersheds and native plants.”

The PG&E marketing campaign for ClimateSmart includes promotional inserts in power bills, direct mailings, newspaper and radio ads, and a website. The company is authorized by state regulators to spend $16.3 million marketing and running the program.

To some environmentalists, the program is designed merely to assuage the guilt of carbon polluters, and little else.

“Indulgences didn’t work in the Middle Ages, and they don’t work now,” said Rolf Skar, a campaigner with Greenpeace USA.

PG&E’s investments in carbon sequestration include a company called California Bioenergy, which captures greenhouse gases emanating from cow manure, and a program that collects and destroys potent ozone-destroying gases from appliances.

The company also targets timber-saving programs, two of which were funded by California taxpayers. PG&E’s ClimateSmart website makes no mention of the public financing of these projects. And none of the company’s ClimateSmart press releases mention it.

But the forestland that ClimateSmart is saving to sequester carbon has long been targeted, and protected, by environmental programs.

In 2004, a large land trust, The Conservation Fund, bought nearly 24,000 acres of forestland in Mendocino County. The property, called the Garcia River Forest, is in California’s Coast Range, nearly 10 miles northeast of Point Arena. Redwoods dot the landscape like bristles on a brush – straight, true, and anywhere and everywhere the steep, shadowy surface allows.

Not far away, The Conservation Fund in 2006 acquired two more properties: 16,000 acres of the Big River and Salmon Creek forests, which are recognized by state officials and The Conservation Fund as one conservation project.

The total purchase price for both projects was $66.5 million.

The state provided nearly $50 million through taxpayer-funded bond money and a $25 million loan. The Conservation Fund and The Nature Conservancy, another national conservation organization, provided an additional $10.5 million. Private donors, including the charitable arms of major housing developers, such as Centex and the ACE Group, donated the rest.

The land is not just sitting idle soaking up carbon. In 2004, The Conservation Fund convinced the state that the forest should become a pilot project that not only would restore and conserve the forests, but also could make a little money.

Based in Arlington, Va., The Conservation Fund focuses its efforts and money on land-preservation projects with “environmental and economic value,” including the protection of “working” forests, according to its website. In 2009, the nonprofit reported about $186 million in revenue.

Under the California projects, The Conservation Fund is allowed to log and harvest the redwoods on the property in an environmentally friendly way and sell the timber commercially. The group also promised to put permanent legal restrictions on the land that would keep it out of the hands of housing developers and agriculture forever.

“We wanted to be a model for revenue-producing conservation projects,” said Chris Kelly, The Conservation Fund’s California program director.

Kelly said any surplus revenue received – money that isn’t being used to manage the land, repair roads, restore bridges, pay property taxes or employment costs, or repay loans – will be split with donors, including the state.

But whether that surplus will ever be achieved remains unclear. So far, it hasn’t happened.

Selling carbon offsets

In 2005, The Conservation Fund saw another opportunity for making money on the timber tracts: carbon offsets. California and other governments were becoming increasingly interested in the idea of a market for carbon, a cap-and-trade system that could be used to offset greenhouse gas emissions.

The Conservation Fund put its carbon stores up for sale. Since 2008, PG&E has bought almost 935,000 metric tons of carbon for its ClimateSmart program, at an undisclosed price.

According to Kelly, the forests are capable of generating more than 1.4 million credits. Although Kelly would not name other buyers of The Conservation Fund’s timber credits, he said they included utilities, investment firms and traders.

The California Public Utilities Commission allowed PG&E to buy carbon offsets for an average of $9.71 a metric ton, which would indicate it bought the credits for nearly $10 million. But Romans, the PG&E spokeswoman, would not reveal the specific price the utility paid.

Company press releases tout the program as a “first of its kind” and a means for PG&E to work with its ratepayers to “make a real difference in preserving the health and natural beauty of the planet for ourselves and future generations.”

Others aren’t so sure.

“We’ve said repeatedly that the ClimateSmart program is a huge waste of money from the customer’s standpoint,” said Mindy Spatt, a spokeswoman for The Utility Reform Network, a PG&E watchdog.

The fact that the property was bought using money from the state provides more evidence toward that position, she said.

And although some contend the credits may be “fake” because the forests already had been protected, Kelly contends they were critical for the forests’ survival. Without the money, he said, they would have been forced to cut down more trees.

If The Conservation Fund had “not received the offset revenues, we would have been compelled to actually increase harvest levels (within the limits permitted by our conservation easements) to pay our loans, cover management and cover other expenses,” Kelly said.

PG&E’s Romans echoed this claim. She said the money the utility paid to The Conservation Fund was essential for keeping the trees safe from over-harvesting.

“The ClimateSmart program allows The Conservation Fund to reduce selective harvesting in order to pay for the activities to bring the forest back to a healthy state,” she said.

But The Conservation Fund didn’t need PG&E’s money for that.

When it requested nearly $50 million from the state to buy the land, in 2004 and 2006, The Conservation Fund already had promised to provide public access, protect the watersheds and rivers, and “restrict harvest” volumes of the trees, according to documents from the California Coastal Conservancy and Wildlife Conservation Board.

Kevin Bundy, a senior attorney with the Center for Biological Diversity, said the state’s justification for granting the bond money includes “the express purpose of protecting and restoring” the forests.

But The Conservation Fund argues it has a right to sell carbon credits from those very same forests.

Their argument centers on a forest management protocol that allows The Conservation Fund to clear-cut the property to its absolute legal limit, Bundy said. This protocol – written after the sale and approved by the Climate Action Reserve – appears to contradict the state’s reasons for granting the bond money.

The Conservation Fund is arguing that it could harvest far more trees, but is choosing to preserve them instead. These preserved trees are therefore worth something that they can sell – carbon credits for PG&E and others.

But Bundy said a conservation group threatening to harvest a forest that it has acquired for preservation “appears more than a little suspicious.”

“It’s unlikely the developer (The Conservation Fund) would have taken a bunch of public money to acquire, restore and protect a forest, then turn right around and clear-cut it,” he said.

The state, for its part, doesn’t seem concerned about the situation.

Dave Means, assistant executive director of the Wildlife Conservation Board, said his agency provided the money at a time when carbon credits weren’t on anybody’s radar.

And Dick Wayman, spokesman for the State Coastal Conservancy, said “this type of revenue generation (is) entirely consistent with the purposes of the acquisitions and the related authorizations for state funding.”

This story was edited by Robert Salladay and copy edited by Nikki Frick.

California Watch, the state’s largest investigative reporting team, was founded by the Center for Investigative Reporting, and is a content partner of KQED and Climate Watch. You can contact the writer at srust@californiawatch.org.