Almost lost amid the Copenhagen media clutter was last week’s meeting of the American Geophysical Union in San Francisco. So this week we’re playing a little catch-up. Lauren Sommer has the second of three posts on things that caught our attention at AGU.

Carbon capture technology has largely focused on the most convenient emissions sources–namely the stacks at large power plants. But as Columbia University’s Allen Wright showed at the American Geophysical Union conference in San Francisco last week, there are other ways to do it.

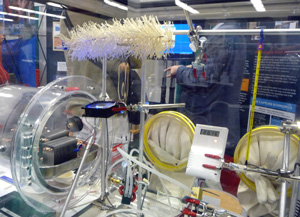

Wright and colleagues demonstrated their “air capture” technology, where carbon dioxide is absorbed straight from the air by something that looks a lot like a gadget for cleaning Venetian blinds. It’s a special plastic material with a sponge-like consistency. Once the carbon is absorbed, the material is exposed to water or water vapor which causes the carbon to be released. It can then be captured. Wright says it captures CO2 three to five times better than a leaf in full sunlight.

On a large scale, this technology might be built into “artificial trees” that could be stationed anywhere around the globe. The prototype, designed by Wright’s Global Research Technologies, doesn’t look much like a tree. It’s a shipping container with a circular, rotating basket on top where the air capture units are exposed to the air. After one rotation, the baskets would be brought “downstairs” where the carbon is captured. From there, the carbon could be geologically sequestered or even used to make beverages bubbly.

Of course, the main criticism of this approach is efficiency. Carbon dioxide is only about 0.04% of the atmosphere, which is why more concentrated sources like power plant stacks get more attention. Wright says capturing carbon from power generation will be important, “but capture at the stack isn’t enough. It won’t do what has to be done. Air capture has the advantage of being able to deal with emissions from anywhere on the planet from any source.”

Cars are one of the sources he’s talking about. Their prototype unit is designed to capture a ton of carbon a day, which would neutralize the emissions from about 20 cars. They hope to get the cost of each carbon-capturing unit down to the price of car, so the cost of reducing a ton of carbon could one day be similar to other technologies.

Still, to make an impact on global emissions, millions of these units would need to dot the landscape. And just as with renewable energy, NIMBY issues are a potential roadblock. But as is a common refrain these days, Wright says if we’re serious about cutting emissions, we’ll need every technology that shows promise.

4 thoughts on “Creating Carbon Sponges”

Comments are closed.

Did anyone talk about serpentine for sequestering CO2? (since we foothillites have plenty…)

Also, Richard Alley’s talk, The Biggest Control Knob: Carbon Dioxide in Earth’s Climate History, was very well received.

This post was a bit of a puff piece for the technology. Among other things, sequestration at the needed scale is likely impractical due to the scale of the needed infrastructure and uncertainty as to whether the sequestered O2 would remnain underground long-term.

And why the cheap shot at NIMBYs? That type of opposition is unlikely since any such sequestration “tree farms” would be located in and around depleted oil and gas fields. Wright was just rubbing a well-known journalistic “paddle point.”

Finally, scientists who think these sequestration schemes are a bad idea (Richard Alley e.g.) would have been thick on the ground at the meeting. Try to find one next time.

Thanks for the comment. On geologic sequestration, here’s a recent piece we did on the criticisms of the approach:

http://www.californiareport.org/archive/R912090850/a

However, Wright mentioned that should the technology pan out, the CO2 wouldn’t necessarily be used for that alone. It could also be sold as a commodity, i.e. for food production, or in emerging CO2-to-fuel efforts. Wright also mentioned that these units could be built at a number of locations, but please let me know if you’ve seen material that says they’d be built solely next to oil and gas fields.

Thanks for the response, Lauren.

The trees could be built anywhere, but then the CO2 would have to be piped to the depleted fields; in other words, there’s no reason to build them anywhere else (unless one is straining to invoke the Curse of the NIMBYs). Re other uses, Wright is being overly hopeful; given the relative volumes involved, any such technology will live or die based on sequestration. With the thermodynamic hill it has to climb, I expect that CO2-to-fuel will join fusion as a permanently receding technology of the future.

Please note that your last sentence is a bit confused: “But as is a common refrain these days, Wright says if we’re serious about cutting emissions, we’ll need every technology that shows promise.” If we’re serious about cutting emissions, we’ll do things to cut emissions. Sequestration technologies don’t. Worse, people may be misled into thinking that emissions aren’t such a critical problem if sequestration is seen as a live option. I’m afraid that articles like yours that don’t describe how difficult it will be to actually implement such technologies mislead in exactly that way.