This is the third in a series of dispatches from Sweden, where Ingrid Becker is touring facilities for storage of nuclear waste. These posts preview an upcoming radio series on The California Report.

The panel advising President Obama is recommending the United States “proceed expeditiously” to establish one or more consolidated “interim” sites for storing high-level nuclear waste. Expeditious isn’t a word often associated with the U.S. Department of Energy’s troubled waste siting program. And, commissioners didn’t say where they would suggest putting the spent fuel, but Yucca Mountain certainly wasn’t mentioned in the series of draft reports from the Blue Ribbon Commission on America’s Nuclear Future. What the commissioners did recommend is that a new organization –independent of the Department of Energy — be formed to develop a waste disposal program. The idea didn’t set well with some House Republicans.

Meanwhile, the political wrangling over Nevada’s Yucca Mountain as a permanent vault for nuclear waste is exposing the federal government to substantial future penalties for breaking promises that it would take care of the spent fuel from nuclear power plants.

A new report from the U.S. Government Accountability Office details how agreements with at least two Western states — Colorado and Idaho — may be threatened by termination of the Yucca Mountain repository program, and could result in penalties of up to $27.4 million annually.

Against this backdrop, Climate Watch continues its overseas reporting trip to explore what another technologically savvy country, Sweden, is doing with it’s high level radioactive waste.

I’m grateful that GPS is now standard equipment for many cars. Without it I might still be lost on the back roads of Sweden in my rented Volvo.

On this leg of the journey I’m checking out the central repository where Sweden is storing the waste from its ten commercial reactors temporarily, in water, until a permanent geologic repository is built. A company brochure (available only as a PDF download) describes the storage process at the facility known as Clab.

Clab is in an area just outside the historic coastal town of Oskarshamn, about 155 miles from Stockholm. Despite several road signs, I had a little trouble finding the place, partly because I kept backtracking. Somehow I could not quite believe that a two-lane country road surrounded by forests and small farms could really be leading to both a nuclear power plant and the place where all the country’s nuclear waste goes.

Once I do arrive, I’m greeted by Brita Freudenthal of the Swedish Nuclear Fuel and Waste Management Company, or SKB.

Before we enter the controlled facility we must slip on rubber shoe covers, a hardhat and protective jacket, and then strap on a monitor calibrated to set off an alarm should it detect any unusually high levels of radon.

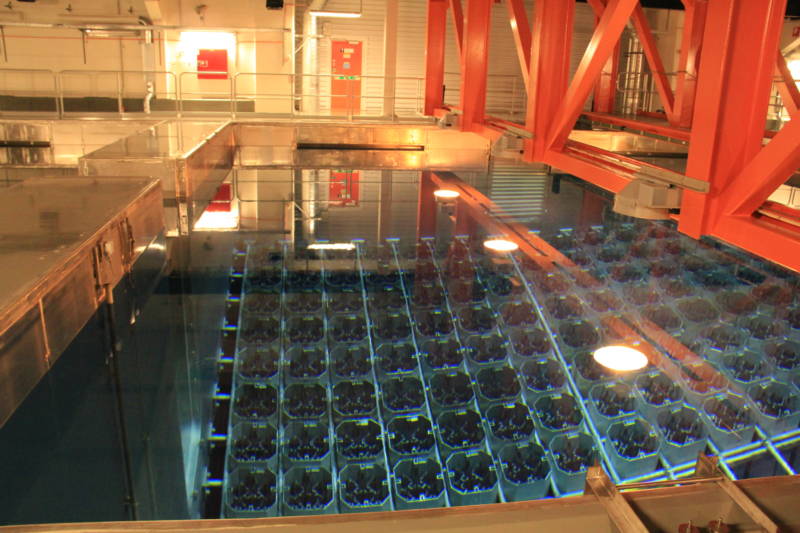

Under Sweden’s unique system for temporarily storing high-level radioactive waste, a specially designed ship carries the spent-fuel assemblies from the coastal reactors to this central facility which is built underground deep in the bedrock. There the waste is submerged in huge pools to shield against radioactivity.

The spent fuel assemblies arrive in casks, which are placed under the water in open steel canisters designed to prevent spontaneous nuclear reactions.

SKB says it has never had an accident here but there’s no escaping the fact that this is dangerous stuff. As the tour continues we find ourselves peering directly into one of the crystalline pools and examining curious geometric patterns formed by the sharp lines from dozens of containers filled with uranium dioxide pellets. Freudenthal drives home the point.

“We have here about 2,000 tons that you are looking (at), and you can stand here as long as you want to,” she tells me before quickly adding, “If we take one of these bundles out of the water I will give you 20 seconds to leave this room alive.”

Storing the high-level waste in water is not unique to Sweden, but this is the only country that collects it in one central facility owned and operated by a private company. Clab employs 100 people and is designed to hold up to 8,000 tons of spent fuel, though its current license limits it to 5,000 tons. Swedish nuclear industry officials believe concentrating the fuel in a single facility is safer than storing it near the power plants or spreading it around to several sites as the U.S. and other countries with nuclear power do now.