While doctors can identify a source of infection about half the time, the study, published Monday in the journal Pediatrics, shows that siblings –- as young as four and a half and as old as nine –- transmitted the disease in over 35 percent of cases with mothers responsible for infecting their babies in about 20 percent of cases.

In the past, mothers were the most common source of infection.

Whooping cough causes acute spasms of coughing, which are typically followed by high-pitched “whoops” in the struggle to breathe. Infants, especially those too young to be vaccinated, face the greatest risk of severe illness and death from pertussis, as the deadly parasite overwhelms their still developing lungs. About half of infected babies must be hospitalized.

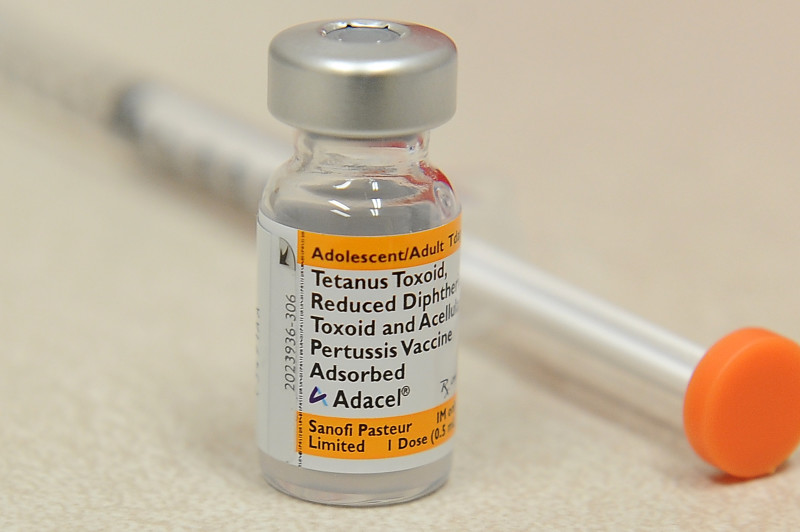

For years, health officials have recommended that all pregnant women get a Tdap shot, says Tami Skoff, an epidemiologist with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and lead author of the study.

“By vaccinating during pregnancy,” Skoff explains, “the mother passes protective antibodies to her baby that protect the baby against pertussis during the first few critical months of life, before the infant begins their own pertussis immunization.”

Early studies in the United Kingdom show that vaccinating during pregnancy is a highly effective strategy to protect infants, says Skoff.

After the UK program was introduced in 2012, babies whose mothers were vaccinated against pertussis at least a week before birth had a 91 percent lower risk of contracting the disease than babies whose mothers did not get a shot.

With the shift in disease transmission from mothers to siblings, should recommendations for a booster be shifted younger than the current age of 11, if mom is expecting a baby?

That’s not a trivial decision, says Art Reingold, a UC Berkeley professor of public health. “Given what we know about the fairly rapid decline in vaccine-induced protection, one would want to at least model the likely effects of shifting the age for a booster.”

What’s more, because protection from the vaccine starts to fade from about 98 percent effectiveness to about 70 percent five years later, changing the timing of the booster could simply shift the burden of disease to other age groups, says Skoff.

The most effective strategy is to get all pregnant women vaccinated during the third trimester to protect babies for the first months of life, when pertussis is most likely to cause severe, life-threatening illness, says Reingold. The next most important thing to do, he says, is to make sure young children get all their shots.

With an unknown source of infection for about 50 percent of cases, it’s still important for anyone who spends time with infants to be up to date on their pertussis vaccinations. Not just children, but all adults, too, including grandparents and caregivers.

This “cocooning” strategy has been recommended since the Tdap booster was introduced in 2005. But it’s proven difficult to implement, says Reingold, in part because many adults are not inclined to get vaccinated. But even if they were, it might not matter.

The current “acellular” vaccine, which contains fragments of the parasite, was introduced in the late 1990s to replace the whole cell version. The whole cell vaccine afforded longer lasting protection but also caused more side effects.

In pertussis, the disease is caused by toxins that are released by bacteria. The pertussis vaccine protects you against those toxins, but may not prevent you from spreading the bacteria to others — and causing illness in them.

Already this year, California has seen more pertussis cases, excluding the two recent epidemics, than in any year since the 1950s.

Public health experts would love to develop a new vaccine that is not only safe but also affords protection over the long haul. But the incentives for manufacturers to invest substantial sums in the needed research and trials are extremely limited, says Reingold. “I don’t expect a new vaccine to provide us an alternative solution in the foreseeable future.”

Until then, he says, nothing offers better protection to an unvaccinated baby than being born to a recently-vaccinated mother.