“It saves time because they don’t go looking for things – they know where they are,” Willsey said.

Private hospitals in places like Seattle and Wisconsin started using Toyota’s system a decade or more ago. But the idea is newer to safety net hospitals -- medical centers that historically have served large numbers of poor people. With the Affordable Care Act, these patients are gaining insurance coverage, and safety net hospitals are facing pressure to keep them from going elsewhere for care.

In California and elsewhere, some medical professionals have expressed skepticism that a process used to build cars can be translated into treating patients. Others doubt whether the changes are sustainable.

DeAnn McEwen, a health and safety specialist with National Nurses United, said lean management reduces nursing to a series of standardized tasks.

“The problem with that is patients, of course, are not widgets and nurses are not robots,” she said. “And nursing care is not a commodity but a service. It’s a process that requires critical thinking and the application of judgment.”

Research and experience from around the country, however, has shown that using Toyota’s techniques in hospitals can improve quality and safety for patients, said Kelly Pfeifer, director of high-value care at the California HealthCare Foundation. The foundation helped fund implementing lean projects at Harbor-UCLA and four San Francisco Bay Area hospitals -- San Francisco General Hospital, Contra Costa Regional Medical Center, San Mateo Medical Center and the Alameda Health System.

Toyota provides its consulting services through its nonprofit arm and did not charge a fee to these nonprofit hospitals.

Changes inspired by the Toyota process had direct results, including reducing the time patients spent at the hospital and decreasing medication errors, according to the foundation. They also saved money. Just reducing surgery cancellations saved San Mateo Medical Center nearly half million dollars, the foundation said.

Susan Black leads the effort at Harbor-UCLA. Her team works closely with administrators, doctors, nurses, clerks and janitors to streamline and standardize everything it can.

“This is not a flavor of the month,” she said. “We have a real need to do better, to do more, improve our access and do it for less. That is part of our survival.”

Toshi Kitamura, a Toyota advisor, says auto production and patient care aren't as far apart as you think. Organizing the equipment rooms and supply cabinets is the perfect example, he said.

“There was a clear translation,” he said. “Just as in the hospital environment, in our environment … we need to make sure we have all the tools and materials we need, and we need to be able to find them quickly.”

Unlike in a car plant, however, Kitamura said saving time can spare people pain and even save their lives.

At Harbor-UCLA, the effort started with an overhaul of the outpatient eye clinic where the process moved so slowly that some patients were going blind just waiting to get scheduled for surgery. During clinic visits, some had to have their eyes dilated twice because they waited so long to see a doctor.

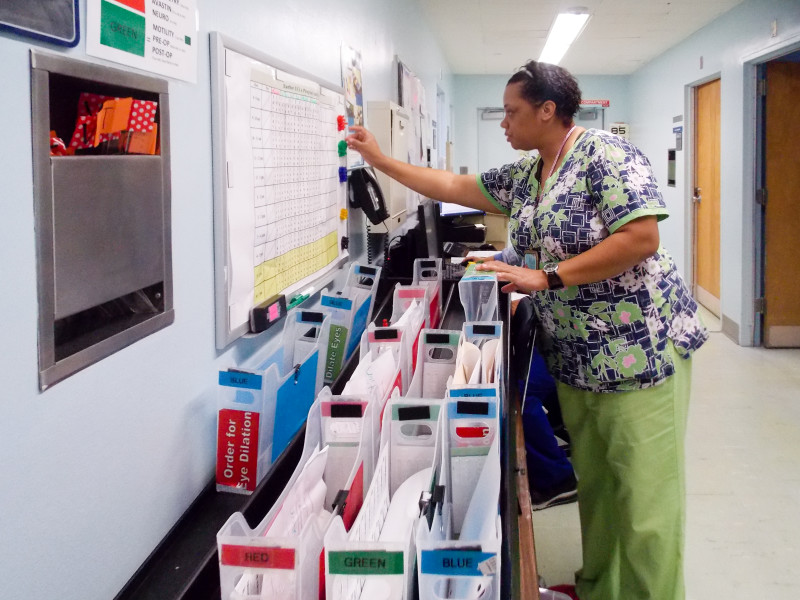

Working with Toyota, staff members picked up the pace: They created a system of color-coded folders so it became clear why patients were there and who they needed to see. They stopped sending patients back and forth to the waiting room during their visits. They put a locked box in each exam room with prescription pads and other medications so doctors could spend more time with patients and less fetching what they needed to treat them.

“Before, it was total chaos,” said Tracie Bell, a nursing attendant. “We had piles and piles of paper. With this new color-coded system … it makes it a whole lot easier for us to do our jobs.”

Within several months, staffers doubled the average number of new patients seen each day. Patients' time in the clinic dropped from 4 ½ hours to just over two. Surgeries were scheduled faster.

Antonio Camargo, 49, a patient at the eye clinic, said he waited months for his first operation, a corneal transplant. But recently, when he needed another operation, he had it within days. “It was a long process before,” he said. “Now it’s better.”

Downstairs, doctors and nurses at the primary care clinic are in the early stages of adopting Toyota’s strategies. But Darrell Harrington, an associate medical director for Harbor-UCLA, said one thing is already clear: “There is a lot of waste of movement and waste of time.”

On a recent afternoon, Harrington watched as a senior resident came in and out of a patient exam room multiple times. “Walking 50 feet or 100 feet down the hall, and doing that during the patient visit three or four times, is a big waste,” he said.

Harrington stopped the resident. “I am just wondering why in and out three different times?” he asked. The resident said that at least once, he went into the hallway because he didn’t want to turn his back to the patient to type notes into the computer.