Video: Why the New Autism Benefit Is So Important to Medi-Cal Families

Effective this week, Medi-Cal now covers a key autism therapy, and some 12,000 kids stand to benefit statewide. One of the children who will benefit is Timothy Wilson, a bubbly 6-year-old who will now be able to get Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) through Medi-Cal, the state's insurance program for people who are low income. ABA is the clinical standard of care for autism.

Timothy was 2 when he was diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder. “He didn’t say mama, didn’t say dada,” says his mother, Jazzmon Wilson. He threw tantrums and hardly made eye contact. “You just see all your dreams go by the wayside."

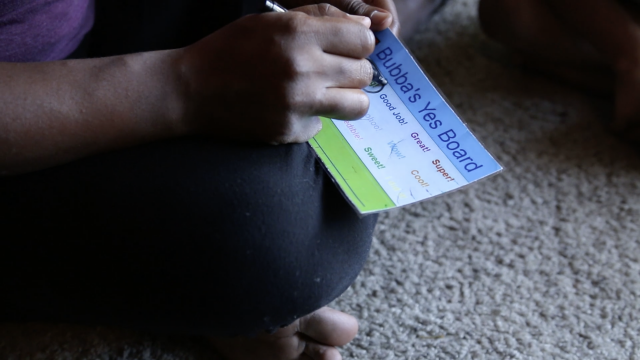

The Wilsons enrolled him in the Regional Center of the East Bay, where children under 3 receive state-funded services. He began ABA therapy, which breaks down everyday skills into bite-sized, learnable portions, then uses repetition, memorization and rewards to reinforce or discourage behaviors. Parents learn to lead their child in the therapy as well. In the video, Jazzmon works with Timothy -- or Bubba as she calls him. Seeing him now, it's hard to believe how affected he was at a younger age.

In therapy, Timothy first learned to point, and eventually to say, “I want.” He started to make swift progress.

“You’re celebrating things others take for granted," Jazzmon says, including little things like simply knowing when her son wants some juice. "ABA gives back the typical experiences (that) you dreamed of when your child was born."

“I felt like the door was cracked for hope,” says Jazzmon. “I thought autism was a death sentence -- we’re not going to go anywhere, do anything -- but this therapy gives you your life back.”

Then the family moved to the Sacramento area and found themselves in a Catch-22. Because Timothy had made so much progress, he was disqualified from further therapy. State-funded regional centers must triage, taking only the more severe cases of developmental disability, so Timothy was turned away from Alta California Regional Center. School districts also provide therapy for autism, but Timothy was turned away there as well.

Without insurance and unable to afford private ABA, Timothy went without therapy. Jazzmon made a decision. “I need to fight back -- he’s losing years," she recalls thinking.

A growing body of evidence suggests that early intervention is key. With therapy, some children stop showing signs of autism altogether.

Fearing they would lose the progress they’d made, the family sued the school district and won a legal settlement that provided for Timothy’s ABA for the past year.

Meanwhile, advocates had been lobbying the state and federal government to make ABA a covered benefit under Medi-Cal. Under new federal rules, that coverage is now reality.

“When I first heard about [the Medi-Cal coverage], I thought to myself, 'My child is going to have a life. He’s going to be able to get a job. Maybe he’ll even move out of my house one day and have a family,” said Jazzmon.

Today, Timothy looks like a pretty typical 6-year-old, at least at first glance. He loves seaweed chips, dinosaurs, his mommy and Mario Bros. But he still has some work to do to be able to interact with kids his age, says Jazzmon.

“Playing Superman or Spiderman, it takes a lot of imagination and sophistication," she says. "A kid that doesn’t know how to do that becomes isolated.”

Timothy gets anxious around other kids, and doesn’t know how to strike up a conversation or sustain one. “Self-esteem is so important at this age,” says Jazzmon.

“My hope is one day he’ll have friends. I know he can learn that with A.B.A,” she says.

David Gorn of California Healthline contributed to the reporting of this story.