It's the word "animated" in the title of the book that is key. That's because when Owen stopped speaking, he continued watching the Disney movies he had always loved. If anything, his fondness for them became stronger. But after some time, Suskind and his wife Cornelia realized that Owen wasn’t merely watching these movies, he was hearing them and learning through the characters.

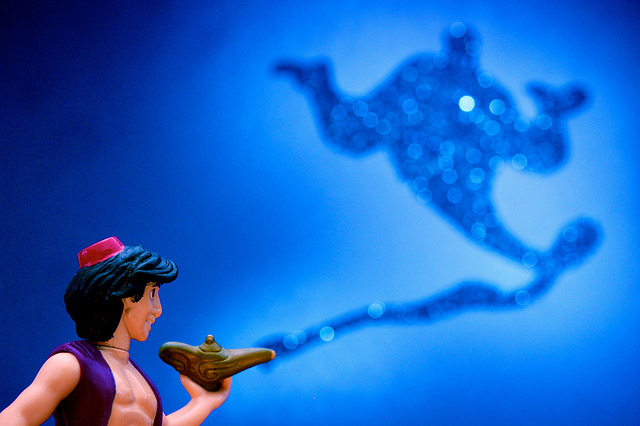

Suskind realized that this affinity was also an opportunity. He used Owen’s affection for Iago, the parrot sidekick in the movie "Aladdin," to try to have a real conversation with his son. He hid under the blanket in his son's room, held up an Iago puppet and, speaking in Iago's accent, father was able to finally –- after more than three years of silence –- connect to son.

Suskind reenacted this conversation for Michael Krasny on KQED’s Forum recently, complete with the accents and mannerisms necessary to convince a child –- then 6 –- that he was talking to a parrot.

The entire family began to use the movies as a way to get into Owen’s head, communicating with Owen as though they were his favorite characters. They began living double lives. In his book, Suskind explains their basement sessions. “During daylight, we go about our lives," he writes. "At night, we become animated characters.” The first basement session was while watching "The Jungle Book," when its trademark song came on. As Suskind describes in his book:

“‘The Bare Necessities’ is a talking song, with the melody broken up by dialogue. … In my best attempt at the voice and inflection of Phil Harris, who voices the bear, I hit play and then say: ‘Look, now it’s like this, little britches. All you’ve got to do is…’

Just as Baloo [the bear] looks at Mowgli [the boy], I look at Owen; he looks squarely back at me – then it happens. Right on cue, he says, ‘You eat ants?’ That’s Mowgli’s line – he speaks it as Mowgli, almost like a tape recording. … Cornelia catches my eye; I shake my head – both of us feeling the same unmoored sensation. The inflection, ease of speech, is something he can’t otherwise muster. But it’s in context, as are his reactions. It’s almost like there’s no autism.”

And it went further. As time progressed, the family regularly used segments of Disney dialogue to speak to Owen and, with time, Owen used them to speak back. For the family, often the “last line [of a scene] is the destination, the inspiring kicker to the exchange. Hearing it, Owen smiles … and then he’ll often do something he’s fearful of.”

But not always. Sometimes, the scenes were just a fun way for Owen and Walt, his older brother, to have a bit of fun. And as Owen grew older, Disney became his dream. He filled stacks of sketchbooks with versions of his favorite characters. He created mental mappings of all the voice actors, directors, and animators that worked on every video. With his parents, Owen visited Disney’s animation studios, where he still hopes to work someday.

The power of the Suskind family's story isn’t just that they persevered and found ways to finally reach their autistic son. The power comes from the fact that their story is not unusual. Many children with autism have what Suskind calls an "affinity." Disney is certainly popular, but so is Tim Burton. Affinities range from maps to logos, wood chimes to hockey stats.

One woman who called Forum said she “felt you were talking about my son. He is 4 years old, he’s autistic," she said, and "he has memorized tons of Disney shows.” Suskind encouraged this mother to continue connecting and finding ways to relate to her son's affinities, because the affinities themselves are “crucial, but just as crucial is to use them to connect [your autistic child] to you.”

Suskind went on to describe a friend whose autistic son has an affection for maps. Though the father was at a loss, Suskind explained that everything can be related to maps, for they “are the two-dimensional rendering of all humanity. … Every town and every map has a history, a narrative.” He said Cornelia made the key revelation: “Respect the affinity, and we respect him.”

Helping parents form these connections through their children’s affinities is why Suskind created the Autism Affinities Project, where parents of autistic children can come together to describe and understand their child’s obsessions. Neuroscientists and psychologists around the country are also teaming up to study both affinities in autistic children and the affinity therapy that the Suskinds essentially pioneered to help their son navigate the world.