She said many people who are depressed often can't find their way to the appropriate treatment if what they're currently doing to address their condition isn't working.

"Unfortunately, what happens is that people don't know enough about their own illness to know if they're not getting better," Arean said.

Dr. Winston Chung, medical director of inpatient psychiatry at California Pacific Medical Center, said there is still a stigma on those with mental health conditions. Discovering physical traces of mental illness, such as genetic traits and biological markers, could help reduce that stigma, he said.

"With cancer, you can see the cells under the microscope. In depression, you can't see it," Chung told the Chronicle. "There's no broken bone, no radiological finding. We need to have concrete evidence, not unlike the cancer cell. Something we can see and reliably associate with mental health issues."

A Risk: Aging White Men

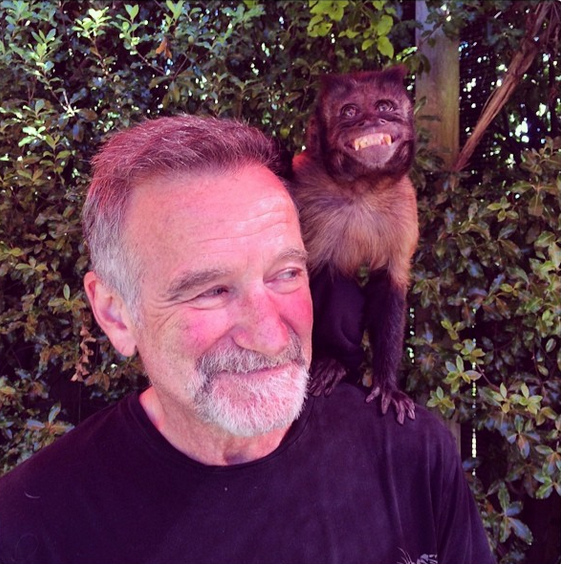

The Washington Post writes that Williams belonged to a demographic with an especially high risk of suicide: older white men. ...

If you tried to create a profile of someone at high risk of committing suicide, one likely example would look like this: A middle-aged or older white male toward the end of a successful career, who suffers from a serious medical problem as well as chronic depression and substance abuse, who recently completed treatment for either or both of those psychological conditions and who is going through a difficult period, personally or professionally.

Last year,the federal government reported the suicide rate for white men increased almost 40 percent between 1999 and 2011. And. because white men use more lethal methods, such as shooting themselves, they account for 80 percent of fatalities despite making up just 20 percent of attempts.

Another factor in the high suicide rate among older men: They are less likely to seek help, Older men may also be prone to reflecting negatively on what they have done with their lives, with an accompanying loss of self-esteem.

"Has the career been worth it, or did I sacrifice my family . . . I think that is part of what happens for people,” Nadine Kaslow, a psychology professor at the Emory University School of Medicine, told the Post.

Christopher Kilmartin, a psychology professor at the University of Mary Washington, said he often refers to aging males as "developmentally unsuccessful, because they’re not equipped to handle the challenges of getting older if they are so tied into their masculinity . . . and making a lot of money."

Said Dost Ongur, associate professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School: “Things aren’t the way they used to be. The power you knew, the control you knew, aren’t the same.”

In 2010, Williams told fellow comedian Marc Maron, on Maron's WTF podcast, that he had contemplated suicide in the past. When discussing what caused him to start drinking again in 2005, Williams told Maron, according to the L.A. Times, "It's trying to fill the hole, and it's fear. You're going, 'What am I doing in my career?' You bottom out. ... People say, 'You have an Academy Award.' The Academy Award lasted about a week, and then one week later people are going, 'Hey, Mork!'"

Comics Prone to Depression

Comics are so prone to depression that the Laugh Factory, a comedy club in Los Angeles, started in-house therapy sessions in 2011. Owner Jamie Masada told the L.A .Times at the time, "This is serious. This is something we have to do. From Richard Jeni putting a gun in his mouth and blowing himself up [in 2007] to Greg Giraldo taking drugs and overdosing [in 2010], I just can't stand to watch all of my family, one by one [self-destruct].

"From Sam Kinison to Rodney Dangerfield to Paul Rodriguez, Dom Irrera — every comic, they have a little demon in them."

Clinical psychologist Ildiko L. Tabori told the Times that research indicated a "higher degree of depression and bipolar disorder in comedians."

"Laughter is a defensive mechanism," she said." It's one of the more mature defense mechanisms, but it still masks whatever it is that's going on inside."

The Washington Post took a look at other comedians who have suffered from depression. Cited is a 2013 TEDxYouth Talk by comedian Kevin Breel called "Confessions of a Depressed Comic."

Breel is just 20, but he’s already had to battle suicidal urges. Outwardly, he said, he hardly seemed like the type you would suspect would be depressed — he was a model student and athlete. “Depression isn’t chicken pox,” Breel said. “You don’t beat it once and then it’s gone forever. It’s something you live with. It’s something you live in. It’s the roommate you can’t kick out. It’s the voice you can’t ignore and the feelings you can’t seem to escape, and the scariest part is, the scariest part is that after awhile, you become numb to it.”

The Chronicle compiled this list of resources in the Bay Area for those who are undergoing a mental health crisis:

-- Suicide prevention/crisis line: (800) 273-TALK (8255)

-- San Francisco General Hospital Psychiatric Emergency Services: (415) 206-8125

-- For any mental health emergency, call the San Francisco Suicide Prevention's 24-hour hotline at (415) 781-0500 or go to www.sfsuicide.org.

-- To find mental health help or other social services in Bay Area counties, dial 211 or go to http://211bayarea.org.