“This article is really critical for laying the ground work for introducing what I hope will be groundbreaking changes in screening and prevention,” said lead author Dr. Laura Esserman, director of the breast care center at UC San Francisco.

Esserman and her colleagues say the improved understanding of the behavior of various cancers provides an opportunity “to refocus screening on reducing disease mortality and lower the burden of cancer screening and treatments.”

Reserve the word “cancer” for cancers

For starters, the writers encourage saving the word “cancer” for those tumors with a “reasonable likelihood of lethal progression if left untreated.”

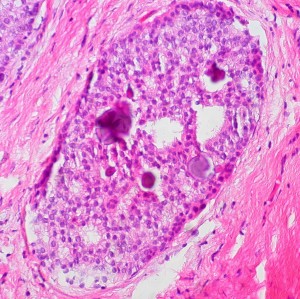

They call for dropping the word "cancer" from pre-cancerous conditions. The panel calls out two conditions specifically: prostatic intraephithelial neoplasia, currently classified as prostate cancer and D.C.I.S. -- ductal carcinoma in situ -- currently classified as breast cancer.

“We terrify (women) with D.C.I.S. thinking they have cancer,” Esserman says, adding that in many cases, “We could wait six months to see if something changes without making people hysterical.”

The panel also calls for the development of highly specialized diagnostic tests to identify these low risk tumors. Many biotech companies are already at work on these kinds of molecular diagnostic tools. It's part of the personalized medicine approach to treatment.

"We need a 21st century definition of cancer"

Dr. Otis Brawley, chief medical office of the American Cancer Society, said he was “largely in agreement” with the panel’s recommendations. In our call, he gave me a short biology lesson on medical science’s understanding of cancer, explaining that back in the 1840s Rudolf Virchow, a German pathologist, used an early microscope and identified cancer cells. Virchow then drew pictures that “profile what we use 160 years later” to diagnose cancer, Brawley says. He explained what while many other areas of medicine have advanced, our definitions of cancer still rely on what Virchow defined 160 years ago. (If you're as startled by this news as I was, check out Brawley’s TedMed Talk.)

Brawley credited a colleague who likened the way doctors classify cancers today to “’racial profiling’ -- something that 160 years ago looked like it would kill you.”

“We need a 21st century definition of cancer,” Brawley said. “It is my belief that papers like this are going to motivate people” to address problems in classifying cancers. The easiest way to get around the problem, he said -- in reference to ductal carcinoma in situ in particular -- is to “remove the word carcinoma."

Despite Esserman's desire to avoid what she called the "rancorous debate" that's been going on around cancer screening and detection, that debate is likely to continue.

Dr. Larry Norton, director of the breast center at New York's Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center told the New York Times that simply changing names doesn't solve the bigger problem that the technology isn't there yet to prove which cases of D.C.I.S. will grow and which ones won't. “I wish we knew that. We don’t have very accurate ways of looking at tissue and looking at tumors under the microscope and knowing with great certainty that it is a slow-growing cancer,” he told the Times.

Next steps

Writer and journalist Shannon Brownlee who literally wrote the book on overtreatment said she was “delighted” by the Viewpoint. She believes the next step is for medical groups such as the American Society of Clinical Oncology and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists to rethink their own guidelines on screening and treatment. By moving beyond a belief that screening is the best way to attack cancer, she says, the recommendations “free us up intellectually to reduce deaths from cancer.”

The Viewpoint writers call for an effort across medical disciplines, including pathology, surgery, imaging as well as advocates “to revise the taxonomy of lesions now called cancer.” They also call for the creations of "observational registries" to generate data so patients with conditions that are unlikely to become cancer can confidently select less invasive treatment options.