I know this is a health blog and not a law blog, but there's certainly plenty of overlap. The Supreme Court's upcoming consideration of the Affordable Care Act springs to mind, for starters. Now, we have public health and the law intersecting over food marketing and children.

Since 2006 when the Institute of Medicine (IOM) filed its landmark report Food Marketing to Children and Youth, health advocates have been agitating to alter the mediascape of advertising children are immersed in every day. Food companies spend more than $1.6 billion [PDF] each year marketing food and beverages to children and teens.

The IOM concluded that food marketing efforts aimed at children were "out of balance with healthful diets and contribute to an environment that puts their health at risk." Additionally, the authors wrote, "television advertising influences children to prefer and request high-calorie and low-nutrient foods and beverages."

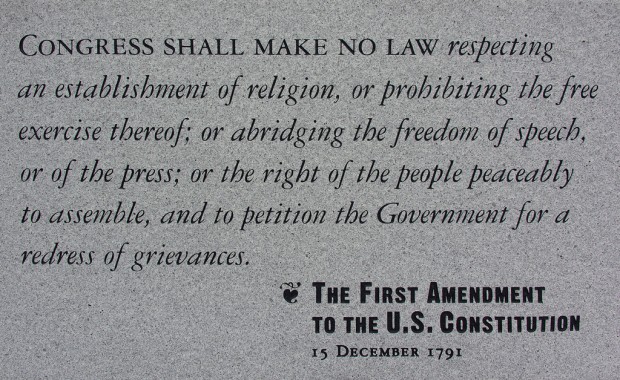

To public health advocates, limiting advertising to children seemed like a good idea. But food companies have long countered that their ads are protected by the First Amendment.

Americans clearly hold a certain degree of reverence for the First Amendment. But free speech is not an unlimited right. And just as Oliver Wendell Holmes said the First Amendment does not protect anyone from "falsely shouting fire in a theater," two recent analyses say the First Amendment doesn't necessarily give food marketers the unregulated right to advertise to children either.

Samantha Graff co-authored both those analyses, one for the American Journal of Public Health and one for Health Affairs. Graff is the director of legal research at Oakland's Public Health Law and Policy. "My goal in these two articles was to clarify that it is not the First Amendment here that is a major impediment to government action to improve the food marketing environment for children."