January 18, 2012: This post has been updated to reflect the family will meet with the hospital.

The story of a three-year-old girl, Amelia Rivera, who was apparently denied a kidney transplant last week at Children's Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) has sparked outrage and debate. Amelia's mother, Chrissy, asserts that a CHOP doctor said Amelia was being denied because she is "mentally retarded."

Amelia suffers from a rare genetic defect, Wolf-Hirschhorn syndrome, which results in severe developmental delays, a characteristic facial appearance, intellectual disability and seizures.

Amelia's mother, Chrissy, detailed the exchange with the doctor in a blog post published last Thursday. She said the doctor started the meeting by placing two sheets of paper on the table in the conference room, in front of Chrissy and her husband, Joe:

I can’t take my eyes off the paper. I am afraid to look over at Joe because I suddenly know where the conversation is headed. In the middle of both papers, he highlighted in pink two phrases. Paper number one has the words, “Mentally Retarded” in cotton candy pink right under Hepatitis C. Paper number two has the phrase, “Brain Damage” in the same pink right under HIV. I remind myself to focus and look back at the doctor. I am still smiling.

He says about three more sentences when something sparks in my brain. First it is hazy, foggy, like I am swimming under water. I actually shake my head a little to clear it. And then my brain focuses on what he just said.

I put my hand up. “Stop talking for a minute. Did you just say that Amelia shouldn’t have the transplant done because she is mentally retarded. I am confused. Did you really just say that?” ...

I point to the paper and he lets me rant a minute. I can’t stop pointing to the paper. “This phrase. This word. This is why she can’t have the transplant done.”

“Yes.”

I begin to shake. My whole body trembles and he begins to tell me how she will never be able to get on the waiting list because she is mentally retarded."

Amelia's case raises all kinds of questions, raised thoughtfully and pointedly, by Lisa Belkin in the Huffington Post. Belkin was a medical reporter at the New York Times for many years and wrote a book about ethics decisions at hospitals. She believes the doctor's refusal to put Amelia on a waiting list is about more than mental retardation. As Belkin writes:

She is being denied a donor transplant because she has a cascading syndrome that will shorten and limit her life, meaning that kidney will not "save" her in the way that it might someone who starts out healthier. In cold clinical terms this means that everything it takes to undergo a transplant -- the medications, the repeated biopsy procedures afterwards, the constant monitoring and machinery -- are difficult and sometimes impossible compared with a child who is less impaired. The less mobile a patient is, the far greater the likelihood that she will develop an infection, or pneumonia, or a host of other complications that make it probable that the transplant will eventually fail. Which, in those same cold clinical terms, would make it a waste of an organ.

In a world with unlimited organs it would be reprehensible to deny anyone a transplant because of her limited lifespan, her limited understanding, or her inability to go on to lead a life as full as some other child might. But organs are not unlimited, and there is no way around these choices. It is a most imperfect and wrenching system. It is inexact and capricious. It brings me to tears as I write about it. But it is the best way we have at the moment.

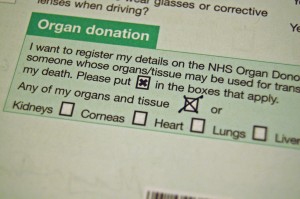

But then we get to the most perplexing point of all. The Riveras say they were not asking for Amelia to be put on a donor list. In her post, Chrissy says both she and Joe wanted to see if either of them could be a suitable donor, called a "living designated donor." (People have two kidneys, but in most cases, need only one to survive). If neither of them matched, they planned to ask their "large family" to donate. And still the doctor said no.