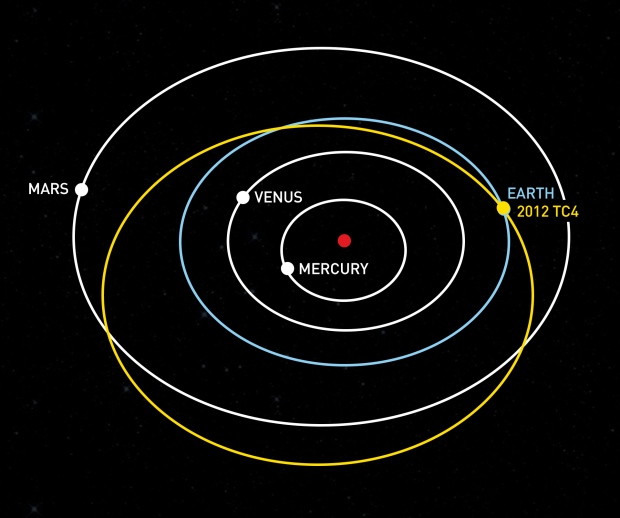

On Thursday, October 12, a small asteroid named 2012 TC4 will pass relatively close by our planet— at an astonishing 5 miles per second. This asteroid’s last close flyby was in 2012, only days after it was first discovered. But you can relax: it won’t hit us.

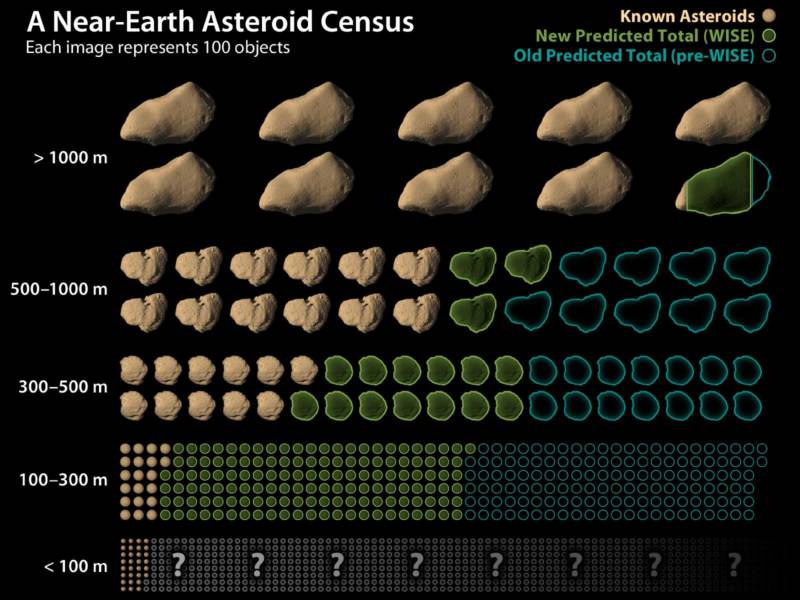

Astronomers, of course, are not relaxing, but taking the opportunity to hone their ability to detect and anticipate future encounters with near-Earth asteroids, the legions of space-rocks whose orbits carry them to within 120 million miles of the sun.

It is not uncommon for small asteroids to pass close to the Earth. At least a dozen have done so since the beginning of the year. What makes 2012 TC4’s flyby special is that astronomers knew exactly when it was coming because of what they learned from its previous appearance five years ago.

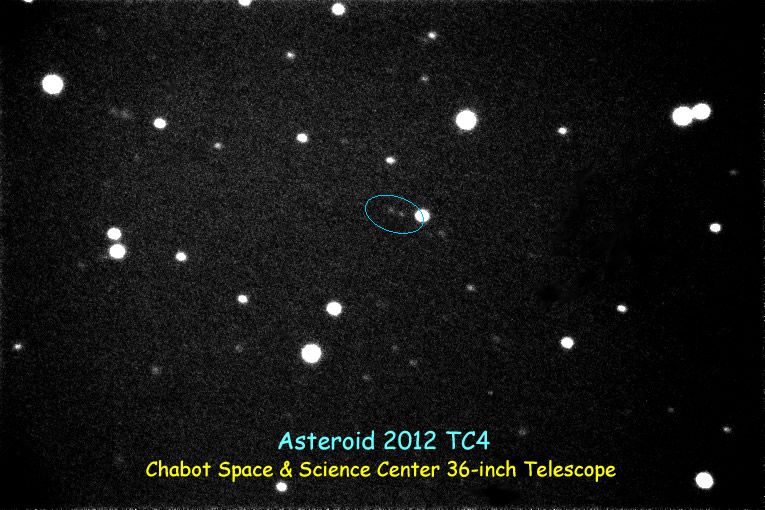

2012 TC4 was discovered on October 4, 2012 by observers at the Haleakala Observatory in Hawaii, only days before its first known flyby of Earth. It was tracked for about one week by several observatories around the world. Then it disappeared once again, passing beyond our ability to detect it.

Data obtained during that week of tracking five years ago gave astronomers enough information to predict another flyby of Earth this October 12, 2017. The first estimates for the distance at closest approach ranged from 4,000 to 170,000 miles from Earth’s surface. That was an ominous range of uncertainty when you consider that 4,000 miles is about half of the Earth’s diameter. Even a small asteroid could cause some local damage if it collided with us.

Then, on July 27 this year, the asteroid was again detected, this time by the Cerro Paranal observatory in Chile, and astronomers have been tracking it ever since. Their observations have allowed them to refine a model of the asteroid’s orbit and make a better prediction for this week’s closest proximity: 27,203 miles, or an eighth of the distance from Earth to the moon. Close enough, but thankfully no cause for alarm.