Local geology matters. Deep waste injection wells are used across America, tens of thousands of them, but they are inducing earthquakes only in Oklahoma, Colorado, Kansas, Texas, Arkansas and Ohio.

Fracking, despite hundreds of thousands of wells using it, has been linked only to a few seismic events large enough to feel in Ohio. Extended oil production and geothermal energy extraction cause similar amounts of disturbance, and carbon dioxide storage is only an experimental technology.

These practices are used in different places, with different results. Scientifically, what they all have in common is that they inject fluids under high pressure deep into the ground. The earthquakes they induce are rarely large enough to feel. Nevertheless, induced earthquakes are a growing problem and they should be prevented, if we can learn how.

In the Science paper, McGarr’s team notes two factors that are important for deep injection wells in earthquake-prone areas. First, fluids are injected into a “crystalline basement.” This means hard, very old rocks that may react to the unexpected lubrication by releasing ancient stresses.

Second, wells inject large volumes of fluid that may migrate where an existing crack—a fault—is ready to move once the conditions change enough. We can’t always tell beforehand where such a fault may lurk.

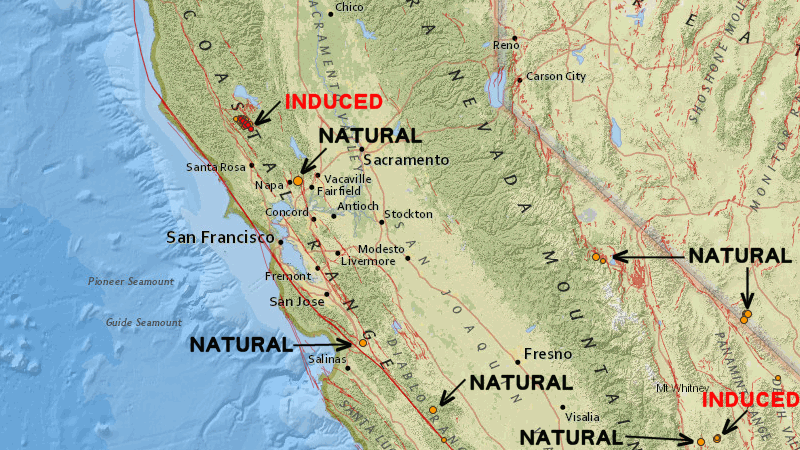

Every place is different. In California, for instance, neither factor applies because the geology simply isn’t right. Here, only geothermal energy production creates any noticeable earthquakes, and those are very localized (for instance at The Geysers). Oklahoma is the opposite, and today it’s America’s poster child for induced quakes.

For planning purposes across the country, the Geological Survey has mapped the nationwide risk of earthquakes. This assessment could include the risk of induced earthquakes too, if we had a way to tell natural and artificial quakes apart. That’s still beyond our reach, according to McGarr’s team.

The more we know about induced quakes, the more we need to know. Government agencies, companies and citizens all have an interest in avoiding unwanted earthquakes, but different costs and benefits. Industry has forged ahead without a full understanding of the science, and government must undertake the research we now need with whatever speed it can muster.

To make progress, McGarr’s team argues, “the importance of seismic monitoring cannot be overstated.” They advise improving networks of seismometers to catch the tiniest earthquakes. These may detect warning signs as part of the “traffic light” systems used in some places (like Weld County, Colorado) to regulate the pace of wastewater pumping. Well fields might also be denied permits or relocated where they won’t affect people.

Next, the authors recommend that these seismic networks make their data public in real time. They urge industry to do the same with its data, “such as daily injection rates, wellhead pressures, depth of the injection interval, and properties of the target formation.” Having all the relevant data openly shared would give everyone a better shot at minimizing the problems we’ve created.

Every state has its own mix of geology and industry, so a nationwide policy can’t cover everything. But it could go far, because almost the whole nation is prone to natural earthquakes—major ones struck Boston in 1755, the Midwest in 1811-12 and South Carolina in 1886. The most widely felt earthquake in American history damaged the Washington Monument in 2011. Not to mention California. And I’ve never heard a seismologist say that we have enough seismometers.