By now everyone knows the word “Anthropocene,” a name pregnant with meanings. It uses the language of geological time divisions to suggest that the effects of modern civilization have made the Earth system itself operate differently. The Anthropocene has become a powerful hallmark of climate-change/global-warming rhetoric.

“Anthropocene” was coined in 2000 by an Earth scientist, Paul Crutzen, who was speaking to an audience of his peers. Geologists have always accepted its premise, for geological reasons—centuries of land-use changes and river damming really have altered the natural balance.

For several years a formal committee has been exploring whether to add an Anthropocene time unit to the end of the geological timeline, where the Holocene Epoch is today. Their work has meant a lot of head-scratching in the profession. Do we need the Anthropocene to do our work? What should its boundary be? How could we determine the boundary based on evidence in the field?

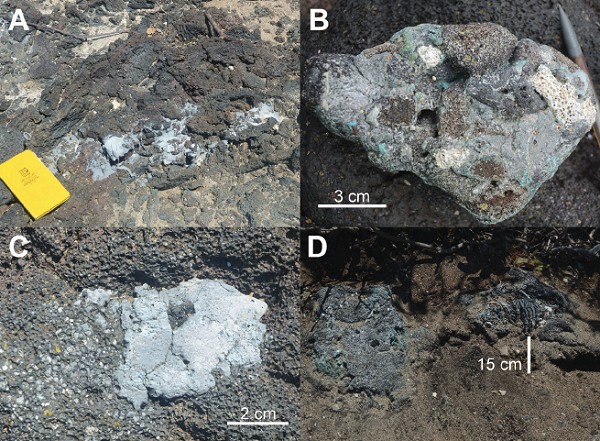

Geologists have always joked about the “Era of Broken Glass” among themselves. But in the open-access journal GSA Today, three researchers have described a substance that may well outlast humanity and remain in the rock record as a worldwide marker. It’s a concrete-like rock made of plastic and sediment that they dub “plastiglomerate.” The researchers are geologist Patricia Corcoran, artist Kelly Jazvac (both of University of Western Ontario) and marine researcher/activist Charles Moore (Algalita Marine Research Institute), and their field area was remote, plastic-littered Kamilo Beach in Hawaii.

Plastic effectively lasts forever, but it’s not usually considered a geological material because it does eventually break down under sunlight and chemical action. It’s lightweight and tends to avoid being buried, which would preserve it pretty much indefinitely. However, the researchers found that plastic can be densified by melting it and mixing it with beach sand and other crud, forming a conglomerate-type solid.