By Sanden Totten, KPCC Science Reporter

How do you map something you can’t see? That’s the question state geologists face as they work to locate dangerous earthquake faults throughout California. During a quake, these deep fractures can cause what’s known as surface faulting, when a fault splits the ground above it, creating a visible crack in the earth or shoving one shelf of land under another. This happened in 1971 during the 6.6 magnitude Sylmar quakein Southern California. Many buildings and roads sitting directly on the fault lines were torn in two.

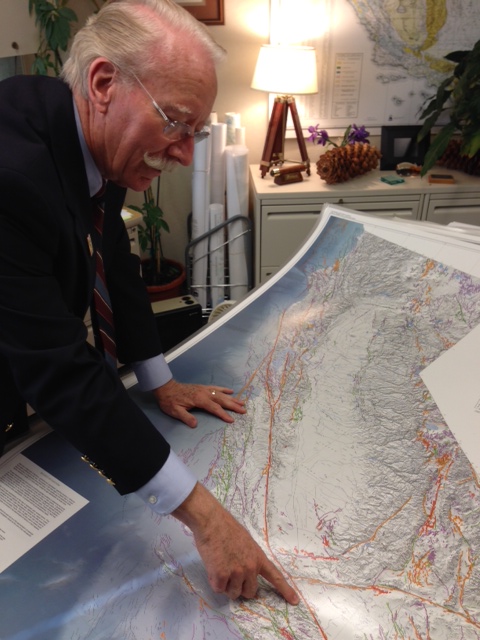

The year after Sylmar, state legislators in Sacramento passed the Alquist-Priolo Act. It requires the California Geological Survey to compile detailed maps of active faults and it bans developers from building directly on top of them. John Parrish is the head of the California Geological Survey, the state agency tasked with creating these Alquist-Priolo Maps. He says California has around 15,000 faults snaking across the state. “But if we said you can’t build near or on any fault that simply would stop California’s economy,” Parrish explained. For that reason, the Alquist-Priolo Act focuses only on what are called active faults: faults that shook sometime in the last 11,000 years. Once state geologists identify an active fault, the law requires them to create a rough map of where it’s located and put a 500-foot buffer zone around it. Any developer looking to build inside that zone must first dig a trench or bore holes in the ground to pin-point the exact location of the fracture, Parrish says. If they find evidence of the fault they must set their building back at least 50 feet from it.

Mapping a Fault

The California Geological Survey is currently mapping an active fault running under the bustling streets of Hollywood. USC Earth Sciences professor James Dolan knows that fault well; he mapped it for an academic research project in the 1990s. “The first step is to just look in great detail at the contours of the landscape,” Dolan said. Dolan says faults that rupture the surface often thrust one side of the land over the other, creating hills known as scarps. One is still visible from the last time the Hollywood Fault ruptured 7,000 years ago. It shows up as a sudden and steep hill just north of the iconic intersection at Hollywood Boulevard at Vine Street. When mapping faults like this and others, state geologists may begin with academic maps like one James Dolan created. But since their findings will carry legal weight, they do additional research as well, including hunting down old aerial photographs, construction records and borehole samples from academic and government archives.

So far, State Geologist John Parrish says his department has created 554 Alquist-Priolo zone maps. But since 2003, he says that work has nearly ground to a halt under budget constraints. Over the past decade, while the state had billions of dollars of budget deficits to close, legislators slashed the California Geological Survey’s budget. Parrish says during that period, the pot of money used for projects like mapping Alquist-Priolo zones was cut nearly in half. “In the last 10 years we probably produced a map or two per year,” Parrish said. “We’ve got about 300 to go. At this rate it will take us 300 years to do that.” Less money is no excuse, for Democratic Assemblyman Mike Gatto. “Every department of government could make that statement,” said Gatto, who represents the Burbank-Glendale area. He says the state’s Geological Survey should use the funds it has to make Alquist-Priolo maps a priority. “Do these government agencies have a duty to still perform what they are mandated to do with the resources that are available?” Gatto asked. “The answer is ‘yes.’” Both legislators and geologists agree that after the next major quake, funding for projects like this will no doubt spike. The problem is that by then the damage may already be done.