The world’s biggest trees are experiencing a growth spurt. Coast redwoods and giant sequoias have grown faster in the past few decades than they have in a millennium. Scientists think climate change is at play, causing longer growing seasons in the Sierra Nevada, which benefit the sequoias, and less fog on the coast, which means more sun for the redwoods.

The fastest-growing tree the researchers found is putting on 1.6 cubic meters of wood a year.

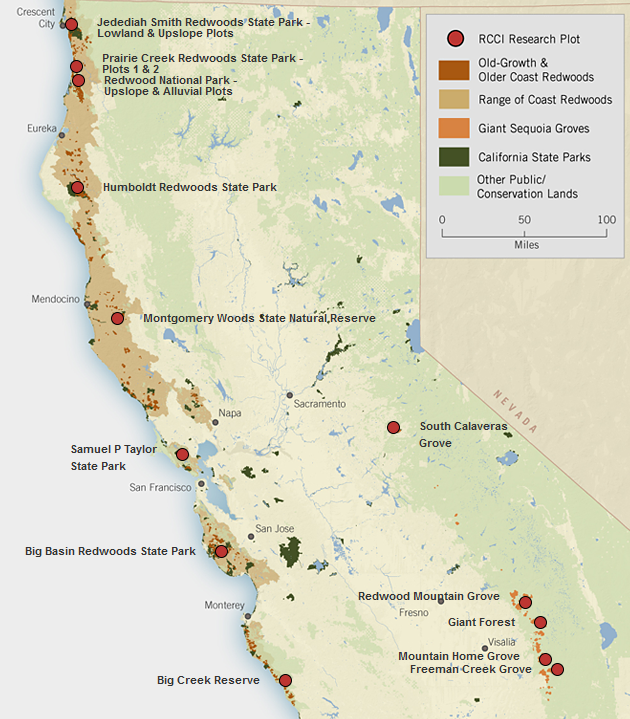

“That’s the equivalent of this tree making 3.2 million pencils every year for the last decade. Which, over a decade, is enough to give everyone in California a pencil. And that’s one tree,” explained Emily Burns, the director of science at Save the Redwoods League, which leads the Redwoods and Climate Change Initiative (RCCI), a research project that also includes scientists from University of California, Berkeley and Humboldt State University.

California’s iconic coast redwoods and giant sequoias live only along the Northern California coast and in the Sierra, respectively. With such a limited range, scientists wondered, how would old-growth forests handle change? Four years into the research, the answer seems to be, they’re loving it, which is hardly what the scientists expected to find. For years, scientists have been warning of the toll that climate change was likely to take on coast redwoods, partly because of reduced fog, which provides them with water.

“I think when we hear about climate change, and especially warming, I equate warming with dry. We know that is hard on the trees and other plants,” said Burns. “What we are realizing is that when the redwoods have enough access to water, even if it does warm up, under the current amount of warming, it’s a great condition for redwoods. That’s a wonderful happy surprise for us.”