He discovered the trend by accident.

Jim Kossin, a NOAA scientist stationed in Madison, Wisconsin, started tracking tropical cyclones to settle a disagreement about the temperature at the bottom of the stratosphere. When he looked at all the data he’d gotten about cylcones’ positions, it was clear: they’ve been wandering.

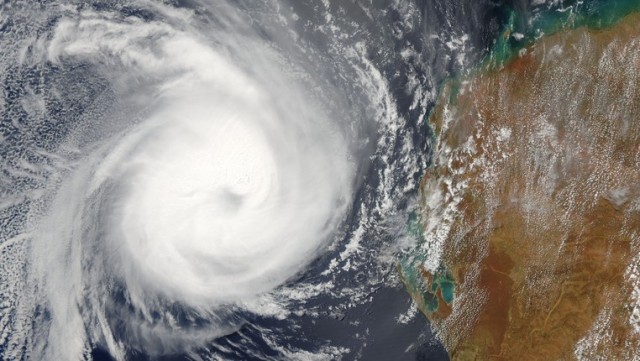

Tropical cyclones, a category that includes hurricanes and typhoons, are rotating storms hundreds of miles wide. Once one forms, it gathers strength as water evaporates from the ocean’s surface; it hits a maximum intensity and then wanes and finally dissipates. What Kossin noticed was that over the last 30 years, even though there hasn’t been a change in the frequency or the peak strength of cyclones, they’ve been hitting that peak farther and farther from the equator. His research, published in Nature, showed that those points of maximum intensity are inching toward the poles at more than 30 miles per decade, putting communities at higher latitudes at greater risk of damage.

This slow exodus out of the tropics reflects changes in the climatic conditions that nurture these storms. Factors like water temperature, humidity, and the temperature difference between the bottom and the top of the lowest layer of the atmosphere combine to determine a cyclone’s maximum possible strength. Whether or not a storm ever reaches that theoretical ferocity, though, depends on the winds it encounters along the way.

“Think of them like a cylinder,” Kossin said. “They like to be vertical.” If there’s a lot of “wind shear,” meaning the wind’s speed or direction changes dramatically as you move upward, that cylinder gets disrupted. Kossin likens the effect of wind shear on cyclones to trying to move a phone book by pushing only on the top few pages. “You can push the phone book as a whole across the table and it's fine,” he explains, “but if you just push on the top and hold the bottom steady, it will shear.” That kind of shear will sap a cyclone’s strength.