If a farmer told you not to pull a weed, would you be worried about him? Maybe you’d insist he get out of the heat and drink some water, or take a vacation.

Believe it or not, that farmer may have good reason to protect his weeds.

In the middle of July 2012, the costliest drought in recorded history had Nebraska in its grip. Not a sprinkle of rain had fallen on Ross Brockley’s farm since June 4, and wouldn’t again until July 31. His half-dozen acres of vegetable gardens were green thanks only to constant watering by hand and diligent weeding performed by Brockley, his wife, Barb, and me, his lone farmhand.

Here in the southeast corner of the state, residents had spent their summer watching scorched soil crack and fields of crops turn brown. On this particular day I noticed a very healthy plant in an empty garden bed. It didn’t resemble anything I recognized as food so I pulled it up.

“Don’t do that!” Brockley yelped from across the garden. “I’m saving it,” he said sternly. “We’ll eat that.”

Really?

The plant looked like a bundle of long red worms, each with several green oval-shaped cartoon ears. It looked more like something suited for a compost pile than a cultivated garden. This drought had clearly taken a toll on Brockley’s mental state.

He picked up the plant I had just discarded, broke off two stems, and put one in his mouth. He held the other in front of my face, indicating that I was to follow his lead.

“It’s purslane,” he said as he chewed, “and it’s primo!”

I hesitantly took a bite and chewed it slowly. “Peppery,” I thought. The crunch felt like a snap pea with the skin of an apple. Then came a blast of citrus flavor. I would have told Brockley that I enjoyed it, but I couldn’t bring myself to interrupt his obvious state of food bliss. I simply looked on as he finished eating the entire plant.

After this introduction to purslane, I started seeing it everywhere -- from my yard to cracks in sidewalks to the shoulders of gravel roads. Even amid the dead stalks of drought-stricken corn, purslane was defiantly rearing its little red branches. The stuff seemed to be laughing in the face of the unrelenting dry spell.

I wondered if my conditioned aversion to weeds had been keeping me from trying other wild edibles, so I sought out an expert.

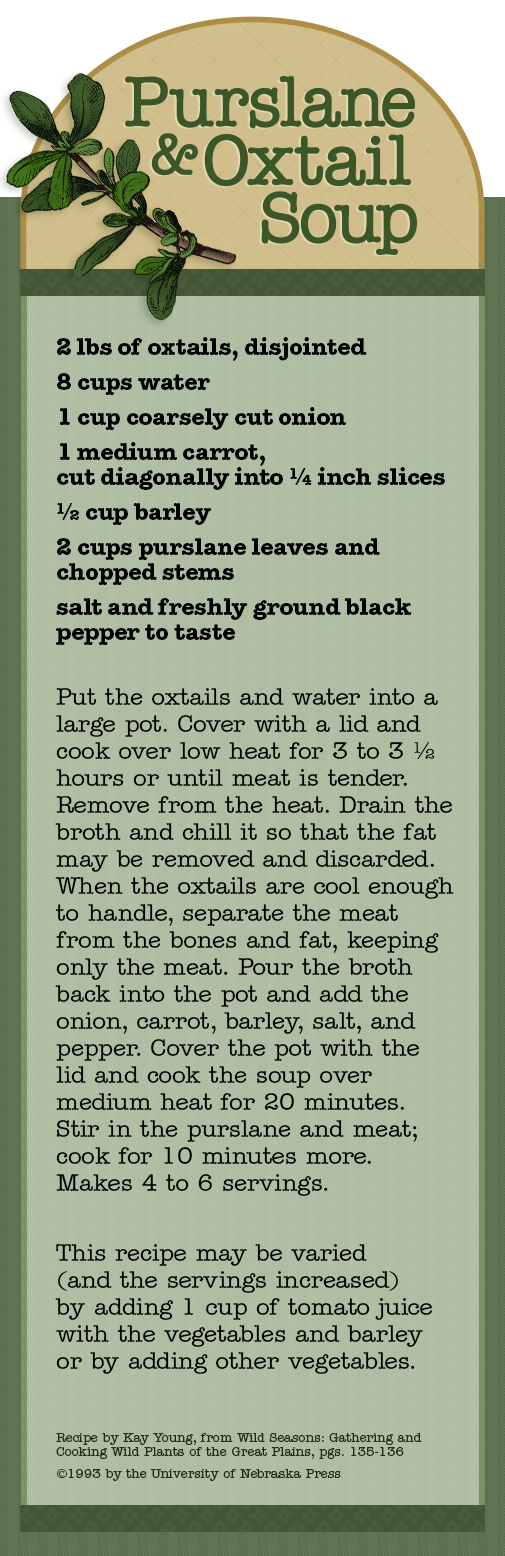

Kay Young is a local legend among plant people. In 1993, she authored Wild Seasons: Gathering and Cooking Wild Plants of the Great Plains, and has been active in Lincoln’s gardening community for decades. The 82-year-old has dedicated her life to local folklore, horticulture, and ethnobotany. A quick tour of her backyard revealed a variety of nurtured plants that one would expect to see in a yard-waste bin.

Kay Young is a local legend among plant people. In 1993, she authored Wild Seasons: Gathering and Cooking Wild Plants of the Great Plains, and has been active in Lincoln’s gardening community for decades. The 82-year-old has dedicated her life to local folklore, horticulture, and ethnobotany. A quick tour of her backyard revealed a variety of nurtured plants that one would expect to see in a yard-waste bin.

She walked me around her property, showing off several edible plants that occur naturally in our prairie ecosystems. We nipped at milkweed, lambsquarter, various flower blossoms, dandelions, and more. Young’s current favorite is Virginia mountain mint, which is native to Nebraska. It makes a refreshing, sugar-free drink when refrigerated in a pitcher of water.

At her driveway we snacked on purslane that she’d planted in flowerpots. She recommended including the leaves in tacos and burritos and praised its ability to replace less reliable greens.

“If you make a sandwich with mayonnaise or salad dressing, it doesn’t get wimpy the way lettuce does,” she said of purslane’s hardy leaves. “And in the summer, when the lettuce is getting bitter, purslane is still just wonderful.”

Okay, so with minimal to no help, purslane and other wild plants are thriving during the country’s worst drought in decades. On top of that, they taste good. But the label “edible” is just a nice way of saying it’s something to chew on that won’t kill you, right?

Wrong. For instance, purslane might be one of the healthiest greens out there. A study by the Center for Genetics, Nutrition and Health, a nonprofit research organization in Washington, D.C., states that purslane is the “richest source of omega-3 fatty acids of any green leafy vegetable yet examined.”

Omega-3 fatty acids contribute to proper metabolism, and according to the same report, their presence is waning in a Western diet that strays from nutrient sources that humans evolved to need.

“In developing new sources of food, the study of dietary composition of wild plants is essential,” the report concludes. “Their cultivation should lead to increased production of plants rich in omega-3 fatty acids and antioxidants, both of which reduce the risk of chronic diseases.”

Reading this made me wonder why we weren’t cultivating nutritious, drought-tolerant weeds like purslane. Could some of these wild edibles become dinner-table staples in the near future?

To answer that question I visited Bob Henrickson, an assistant director of the Nebraska State Arboretum at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

Henrickson agreed that people are failing themselves by not indulging in the prairie’s naturally occurring food sources. He acknowledged that cultivating these so-called weeds would require less water and potentially reduce the need for pesticides and chemical fertilizers, but he was not optimistic that vast fields of purslane, milkweed, or gooseberries would soon replace the established, lucrative crops of the Great Plains.

“We’re never gonna outcompete corn and beans,” he said.

He suggested that the best chance to get wild edibles onto dinner plates on a larger scale is to introduce them to urban gardeners who grow food to support their own dietary values and not their pocketbooks.

“Use them with the attitude that ‘it’s going to enhance my food,’ not that ‘I’m going to save me and the planet,’ and you’ll find yourself using them more and more.”

Back at the farm, Brockley agrees with that sentiment. He just wants to see his customers using common sense in their relationship with purslane instead of worrying about his mental health when he eats it in front of them.

“People say, ‘That stuff grows in the cracks of my sidewalk. I don’t want to eat that.’ But when you think about it, it’s growing in the cracks of sidewalks during the worst drought of most of our lives. Isn’t that exactly what you want to eat?” asks Brockley.

“Whatever is in that plant, keeping it alive and healthy,” he adds, “I want in my blood.”