Aboard the Tugnacious With Dr. Doom

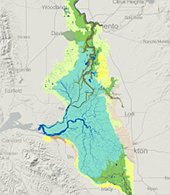

Two-thirds of California residents rely on water pumped through the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta, as its delicate ecosystem teeters on the brink, and its aging levees crumble.

Planners have spent decades searching for a fix. But they'll have to finish the job without the advice of a man who’s played a central role in Delta science.

Jeffrey Mount, the scientist dubbed “Dr. Doom” for his dire pronouncements about the Delta, has retired from his post at University California, Davis. Science editor Craig Miller caught up with him – where else – on the river, aboard his 27-foot cruiser, “Tugnacious.”

This is an edited version of their conversation.

The question of what to do about deteriorating conditions in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta has dogged Mount throughout his 33 years as a professor of geology, as co-founder of the Center for Watershed Studies at UC Davis and going back to Governor Brown’s first administration. I asked Mount – one of the Delta’s most plainspoken explainers, why it matters so much.

Craig Miller: Eight in 10 Californians can’t even tell you where or what the Delta is. Why do they need to know?

JM: Very few Californians get the notion that this is an interconnected system now, with water that comes all the way out of the Trinity River, piped over and into the Sacramento River and down through the Delta, run into canals and ends up in San Diego. I mean really, that’s extraordinary, all the way from the Klamath Basin to San Diego. This is an interconnected network, so 25 million people get some of their water out of the Delta.

CM: You said in an interview that you thought we were down to our last shot with the Delta. What did you mean by that? And what do you think the real chance is that we'll have a long-term solution in hand by, say 2020?

JM: Let me explain why I think we’re down to our last shot. We have deeply entrenched interests, and regrettably it’s not simple. You’ve got farmers fighting against farmers. You have urban interests fighting against urban interests. You have environmental groups fighting against environmental groups, and then they’re all fighting each other, and that makes it wickedly complicated. And instead of coming out of their foxholes, they seem to be digging deeper and deeper foxholes.

Events will eventually dictate how we manage the Delta and I have said many times, and nothing in the last seven or eight years has changed in this, that we’re dealing with a system that is unstable, and it will rearrange itself, whether from floods or earthquakes or rising sea level or changing human demands on the system or invasive species, it is unstable and it is changing and if we don’t get our hands around it now, it’s going to be doubly hard to get our hands around it in the future.

Some believe one way to “get our hands around it” is to move southbound water around this fragile ecosystem – or in the case of the latest proposal, under it, with twin tunnels that would shuttle water from upstream on the Sacramento, more than 30 miles south to serve needs in the Central Valley and Southern California. Mount agrees, saying it’s the only way to comply with current laws that put water needs and the environment on equal footing.

JM: To meet the co-equal goals of the 2009 legislation, I think you’re going to have to have a tunnel or two. Don’t like it, go back and change the policy. You could say, "We’re going to manage this ecosystem. We’re going to go for ecosystem health as the primary objective within it." If that’s the case, at best you want a tiny little pipe – a peripheral garden hose would be the best description of it. You want to dramatically reduce your withdrawals from the Delta, both in-Delta exports and then all those people upstream; all those people like San Francisco, let’s take them for example, they’re taking water from the Delta, they’re just taking it out upstream.

CM: By upstream, you mean up in the Sierra.

JM: Yeah, they’re just taking it out before it gets to Delta, that’s all.

CM: Give me your pithiest version of why a tunnel beats a canal.

JM: Actually I don’t think there’s any difference between the two in terms of system performance, but there are major differences politically. Good luck building a peripheral canal across the Delta given the level of local resistance and changes in our practices of eminent domain. I can completely understand why they want to spend more money and go under the problem rather than over the problem.

CM: We talked a little about this déjà vu aspect of it, this goes further back than Jerry Brown’s first term, this goes back to Pat Brown, doesn’t it?

[box size=small align=left color=white]California's Deadlocked Delta

- Video explainer: What is the Delta?

- Interactive map: Envisioning California’s Delta As it Was

- Feature story: Can the Delta Be Fixed?

[/box]

JM: That’s correct. When the state water project was developed, they knew all along that they had left a hole in it, and that is the Delta. They knew there was a problem even back in the 1950s that the Delta was going to be a major issue. From that point on, this intractable, difficult wicked problem has bedeviled governors, heads of the Department of Water Resources and water managers in California nonstop.

CM: If they were so aware that this was a problem looming, why didn’t they address the problem head on the first time around?

JM: There’s a tendency in water supply to leave the most complicated and difficult problems to later. We are a society – and there’s no difference in the water supply community – that likes to pluck the low hanging fruit and put off the hard work until later. The Delta fix, if there is one, is not simple, it’s not cheap, it involves burning massive amounts of political capital to get it done, and it involves lots of angry people no matter what you do. I can easily understand why people kept putting that one off.

And yet, with all of the rancor that remains in the Delta water wars, Mount sees a light at end of this tunnel.

JM: I can actually say that I think the state government and federal government are starting to paddle together, which has not been the case – it’s actually been one of the principal problems. They are actually starting to look like they’re much more in sync with each other, and that’s a glimmer of hope.

CM: Does that mean you think we have a decent shot at a long-term solution?

JM: I think it’s a 50-50 chance that we’ll get a long-term solution out of this. This is all of California’s problem. I mean this is 25 million people, also two-thirds of the population of California. It’s our problem.

Mount still has some skin in the game. In his new career is as a consultant, he says he wants to help restore rivers, not just talk about restoring them. As for his nickname, “Dr. Doom,” Mount says it was coined a decade ago by then-KQED reporter Tamara Keith, now Capitol correspondent for NPR. It stuck – and Mount still embraces it, though no doubt he’d love to be proven wrong.

Sean Greene contributed to this article.