Climate Threat to Dams Overlooked by Regulators

Climate Threat to Dams Overlooked by Regulators

There are more than 130 hydropower projects in California. They take advantage of steep terrain and gushing mountain rivers to churn out about fourteen percent of California's electricity.

It's a delicate balance, dependent on heavy snow in the winter, and heavy runoff in the spring as the snow melts. But climate change threatens to throw that balance out of whack, a problem that federal regulators have chosen to ignore.

A High-Stakes Game

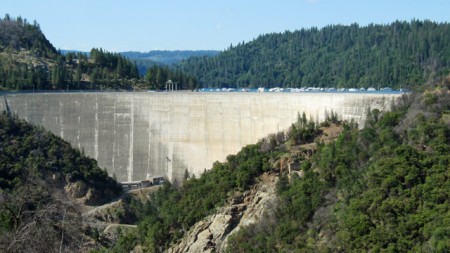

New Bullards Bar Dam stretches across a steep rocky canyon in the Sierra Nevada foothills, about fifty miles northeast of Sacramento. It's the fifth-highest dam in North America, towering more than sixty stories over the North Yuba River.

"I get to run around to all these glorious sites, and work on a multitude of issues," says Geoff Rabone. He works for the Yuba County Water Agency, which owns this and other smaller dams, plus a network of reservoirs, water diversion tunnels and hydroelectric facilities. Standing on top of the spillway, we can see vultures circling below us.

Rabone manages relicensing for the water agency. Every few decades, hydropower projects have to get a new license from the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, or FERC. If you think going to the DMV is bad, be glad you're not a dam. Applying for a new hydropower license takes years and costs millions of dollars. It seems like everything gets considered, from how the dams affect water supply, to endangered species, to whitewater sports.

"We have 44 different studies going on right now," Rabone tells me.

In the end, the new license will dictate how much electricity the project generates, and how much water it releases -- and when -- for the next thirty-to-fifty years. That's why there are so many studies, and why FERC relicensing is so important to water agencies, power companies and environmental groups, among others.

But there's one looming issue that Rabone doesn't have to wrangle any studies for: climate change. FERC doesn't require those.

[box size=small align=right color=white]Water and Power

Explore KQED's multimedia series, Water and Power.

Illustration: Water Needs Power

Illustration: Power Needs Water

Map: California's Hundreds of Dams (and Very Few Undammed Rivers)

[/box]

Climate Change and the "New Normal"

"It's an approach akin to the cliche of putting their heads in the sand," says Steve Rothert, the California director for the environmental organization American Rivers. Rothert says he has asked FERC to include climate change in the relicensing process, but they've turned him down.

Climate change projections for the Sierra Nevada vary. The region may get wetter; it may get drier. But scientists agree that it will get warmer, dramatically affecting the snow where most of the region’s water comes from-- and not just in the distant future. There’s evidence that we’re already seeing effects of climate change in the Sierra.

"And yet the power companies and the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission refuse to consider how climate change will affect these dams and these rivers for the next 50 years," says Rothert.

Josh Viers, an ecologist at The University of California - Davis, is similarly perplexed. He argues that FERC's decision to depend only on historic weather and water records doesn't make sense anymore, especially for licenses that won’t expire for decades.

"Most of the projections for California in particular -- and these are multiple scientists using different models and different assumptions -- all converge on the same idea," explains Viers. "The climate 35 years from now is not likely to be what we see today."

One recent study suggests the emergence of a “new normal” within the next few decades, one in which eight-in-ten winters in the western U.S. will see snow accumulation below what we now consider normal.

Viers says the way California manages water will have to change. Right now, the snowpack itself serves as a reservoir. If it melts earlier, or if more precipitation falls as rain, our man-made reservoirs may have to spill the extra runoff, which could mean more floods in the winter, and more water shortages in the summer.

"We have a lot at stake," says Viers. "So it seems it would be in the public’s best interest if in fact FERC were looking out for the public."

In fact, the strategic planner for one Sierra utility says, when his agency included an entire section on climate effects in its relicensing application, FERC didn’t want it.

Why Not Consider Climate?

FERC officials acknowledge that climate change will have an impact on hydropower, but say the climate models scientists have developed just aren't specific enough to project local impacts.

"There are not really any models yet that are granular enough that we would feel comfortable basing a decision on the impact of climate change on an individual facility," FERC commissioner John Norris told me.

FERC has also said that the focus of relicensing studies is on how hydropower operations affect resources, not how other things -- in this case, climate change -- affect them. Rothert of American Rivers says that's a red herring, though; the studies he's asked for would concern how hydropower projects affect resources in a changed climate.

If federal regulators are "whistling in the dark," Rabone from the Yuba County Water Agency says climate change is very much on his mind.

"It's going to be very interesting to see what happens, if climate change turns out the way it's theorized to work out," he says.

If it does, the job of water managers -- balancing the needs of fish, farmers and power plants -- will only get more complicated as the climate changes, whether or not regulators are paying attention.