With Large Oil Reserve, California Faces Fracking Debate

With Large Oil Reserve, California Faces Fracking Debate

The new oil-and-gas boom that’s sweeping the country may be coming to California. With it comes the controversy over the drilling technique known as hydraulic fracturing – or fracking. Widespread fracking in other states has launched a national debate over the impacts on public health and the environment.

California has long been an oil-producing state, but it’s getting renewed attention because of the Monterey Shale, the country’s largest shale oil resource. It stretches under a large part of Central California. In places like Southern Monterey County, where new oil leases are being offered, the battle for fracking is heating up.

Vineyards and Oil Pumpjacks

Vineyards and farms stretch for 40 miles along the narrow valley around Highway 101, about two hours south of San Jose. “As a coastal growing region, we are the largest planted acreage of Chardonnay, so much more than Napa or Sonoma has,” says Kurt Gollnick of Scheid Vineyards, a winery in the foothills of Salinas Valley.

What Monterey County wineries lack is the name recognition that Napa has - and the visitors that follow. “This is something that we’re trying to change now. We do have very scenic areas of Monterey County,” Gollnick says.

Lately, the focus has shifted to what’s under the ground: oil – and plenty of it. On December 12th, the federal Bureau of Land Management is opening 18,000 acres for oil leases in Monterey, Fresno and San Benito Counties. Some parcels aren’t far from Scheid Vineyards.

“This is where that whole conversation of fracking comes up,” Gollnick says. The oil deep in the Monterey Shale is notoriously tough to extract. Most if it is locked inside the shale rock. But recently, oil companies have gotten a lot better at getting oil out of shale thanks to hydraulic fracturing.

Millions of gallons of water, mixed with sand and chemicals, are injected underground at high pressure. That cracks the rocks, letting the oil out. Around the country, hydraulic fracturing has led to record levels of oil and gas production.

Shale Gold Rush

“Right now there’s a bit of a Gold Rush mentality concerning shale oil,” says Don Gautier, a geologist with the U.S. Geological Survey. He says fracking is nothing new in California. It’s been used for decades.

“What is new right now is that the price of oil is reasonably high. This technology has become very sophisticated. So these explorationists are justifiably optimistic about the idea of being able to get out oil that couldn’t have been accessed just a few decades ago,” Gautier says.

California’s oil shale resource is huge – more than 15 billion barrels in the Monterey formation, according to one estimate. It’s bigger than North Dakota’s oil reserve, where recently, thousands of wells have been drilled.

That has a lot of people wondering – is California next?

Debate Over Fracking

“There is absolutely a danger of California being transformed almost overnight as other areas of the country have been when the fracking boom hits,” says Kassie Siegel, a lawyer with the non-profit Center for Biological Diversity.

“In other parts of the country, we’ve seen contaminated water,” she says. “We’ve seen people who live near oil and gas wells complaining of health effects.”

Whether those impacts are specifically caused by fracking is under debate in many places, but Siegel says it’s enough to be concerned. Her group is suing the Bureau of Land Management over the oil lease sales, saying the agency has failed to review the risks that new fracking techniques pose.

“They are acting as if nothing has changed in the oil and gas industry, but of course everything has changed,” Siegel says.

At the Bureau of Land Management office in Hollister, manager Rick Cooper says they’re offering the oil lease sale because of interest from oil companies. “Any time there’s new technology, then there’s going to be maybe a little buzz and a little interest in areas that hadn’t previously been developed,” he says.

The agency is predicting minor environmental impacts, however, because their analysis doesn’t forecast much new drilling.

“We haven’t seen development signals as of yet. But if we begin to see increased development, it would be at that time that we would pull back and say, well, we probably are going to have to do more analysis,” he says.

A Potential Shale Play

Several oil companies, including Venoco and Occidental, have reported they are experimenting in California’s shale formations. “Certainly our members are exploring how effective hydraulic fracturing is going to be in California,” says Tupper Hull of the Western States Petroleum Association, an industry group representing oil and gas companies.

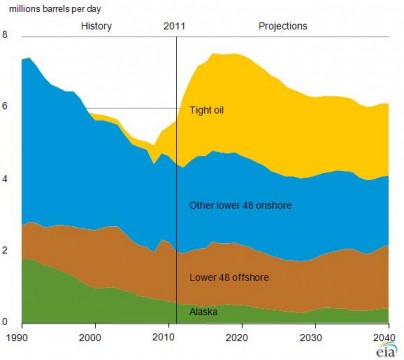

Hull says California’s geology could be challenging for large-scale fracking. The shale layers are messy, bent by seismic forces. But he believes fracking has the potential to boost the state’s oil production, which has been declining for two decades.

“If hydraulic fracturing proves to be successful here as it’s been elsewhere, it’s an extraordinarily optimistic future we’re looking at from an energy point of view,” Hull says.

Back in Salinas Valley, Kurt Gollick says residents are watching. “I can tell you this from our perspective, farming is our number one source of income in Monterey County. It’s an eight billion-dollar industry.”

Gollnick says he hopes the two industries can coexist, but “if fracking introduces contamination to the water or anything else that affects growing practices, then that would be a huge point of conflict, no question about it.”