Everyone knows that women are born with all the eggs they can ever make, right? Well, a recent study shows that everyone just might be wrong.

This doesn’t just change how we think about reproductive biology. It has real world implications for lots of infertile women too.

A woman makes all of her eggs while she is still in the womb. The way it works is that a group of cells called germ cells divides until they are nearly mature. These 400,000 or so cells then wait around until the woman is born and enters puberty. Then, around one cell per month matures and is released. By menopause, the average woman has released about 400 mature eggs.

Scientists thought for a long time that once ovaries made their batch of immature eggs, they lost this ability forever. They were mistaken. This study showed that a woman’s ovaries still have a few cells that retain their potential to become eggs.

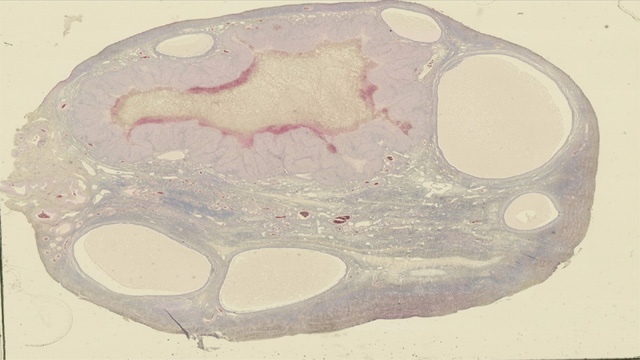

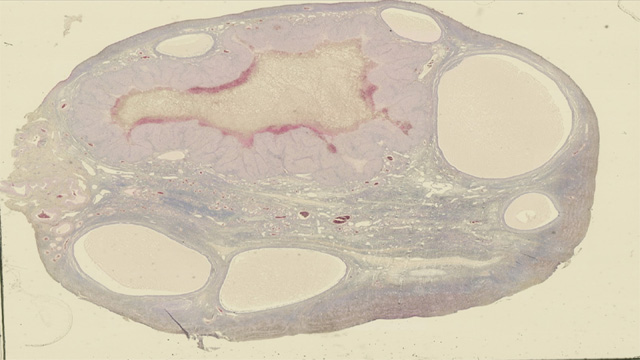

These researchers not only identified these oogonial stem cells (or OSCs), but also managed to collect a few and to coax them into becoming immature oocytes in a petri dish. They then matured these immature oocytes in a mouse’s ovary. These scientists had created new eggs from cells found in a woman’s ovaries.