Standing in the entrance of a Vermont cave in March 2008, it was clear from the dead bats in the snow, another flying in the frigid cold and one clinging to an icicle that something was wrong.

I’m a Wildlife Disease Specialist for the USGS National Wildlife Health Center in Madison, Wisconsin. The Center’s mission is to safeguard wildlife and ecosystem health through dynamic partnerships and exceptional science. I was at the cave with two Vermont Fish and Wildlife Department biologists to learn more about white-nose syndrome (WNS), a new disease that was killing bats in New York, Vermont, Massachusetts, and Connecticut by the thousands.

Bats are fascinating creatures that have evolved very specialized survival skills. One of these is their ability to hibernate to conserve energy by reducing their heart rate, temperature and other body functions to very low levels for extended periods. This allows bats to survive long winters using their stored body fat when their insect food source is unavailable. Although bats may briefly rouse out of hibernation to drink water or move to a different part of the cave, they typically stay deep in their hibernaculum or winter “roost site” until spring.

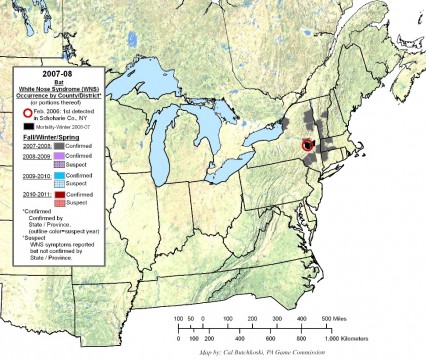

So it was odd in winter 2007 when New York residents reported seeing bats flying during the day and finding them dead in the snow in their yards. Biologists following up on the reports were surprised to find a nearby cave littered with dead bats and a fuzzy white growth on the nose and wings of some of the live bats. The following winter, sick and dead bats were reported in multiple locations in New York as well as Vermont, Massachusetts, and Connecticut. The disease has now spread as far west as Kentucky, as far south as North Carolina, and to four Canadian provinces. It is estimated that over a million bats have died since 2007, making this the largest disease outbreak among mammals in modern times. WNS has spread very rapidly, by bats themselves, and likely also by people moving between affected and unaffected sites.

Click on map for a larger version.