What haunts him about his time in Iraq is the fact that he came home largely unscathed. That was not the case for his best friend, who was badly injured by an IED.

"You start thinking, well, how fair is that?" says Schuler. "Here's my friend, 88 percent burned, two people in his battalion killed. And here I am in a similar situation and we're all OK. It's a tough thing to deal with."

Back in the States, Schuler struggled with problems that will sound familiar to a lot of returning vets. He's had to tame his road rage. And sometimes, he can be a bit withdrawn.

What's gotten him through this is helping other returning soldiers. He is now a fellow for a group called The Mission Continues. His placement is with a group called USA Together, counseling Bay Area vets who are having financial problems.

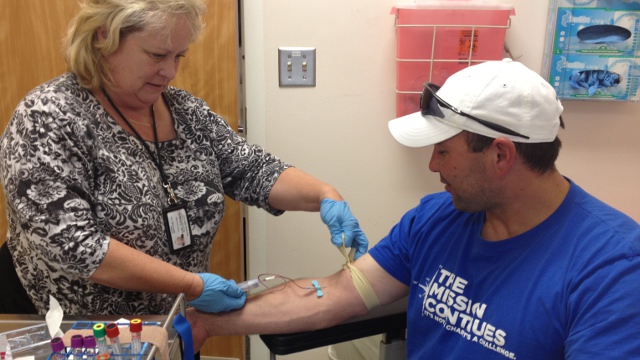

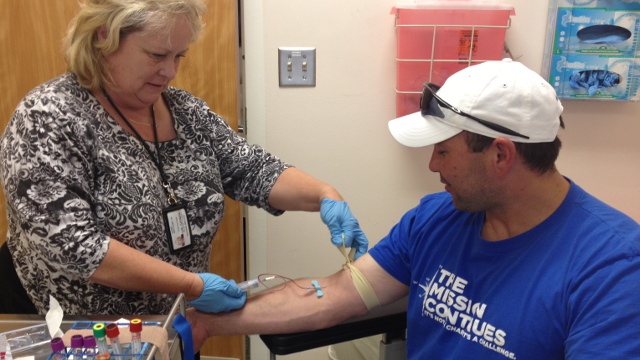

It’s that same impulse -- to help vets – that brought him down to the VA Medical Center in Palo Alto on a recent morning.

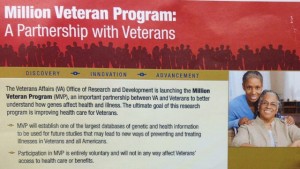

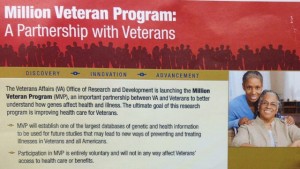

Schuler came to take part in something called the Million Veterans Program, or MVP. It is a project to build the largest database of medical information in the world, with both medical histories and blood samples from one million US vets. The Medical Center in Palo Alto is one of 33 VA hospitals across the country taking part, with the ultimate goal of making participation available to all veterans enrolled in the VA healthcare system. The recruitment will last between five and seven years. In 2012 alone, the program is projected to cost $19.8 million.

What makes this program possible is something that puts the VA well ahead of the curve, when it comes to health care: electronic medical records.

At a time when virtually every other sector of the economy has gone online, medicine has lagged behind. Most American doctors still carry paper files when they go into see a patient. Less than a third of hospitals have digitized records.

But VA abounds in electronic data, says the VA’s Dr. Jennifer Hoblyn. She says in addition to clinical records of its 8.6 million patients, the VA also has annual assessments that it uses to track patients, including evaluations of depression, PTSD, alcoholic substances, traumatic brain injury, and other conditions. All of the information is digitized and available to VA doctors.

"It's an amazing medical record," says Hoblyn, "and it stretches back 25 years."

Now, the VA wants to pair that information -- detached from individual names -- with anonymous blood samples from a million vets. It would be the biggest medical database in the world.

That's an exciting prospect for people like Robert Hiatt, who chairs the Department of Epidemiology and Biostatisticsis at UCSF.

Hiatt says when he started out in his field, researchers would send staff with clipboards from doctor’s office to doctor’s office, pulling folders from shelves and manually tallying up the data.

Electronic databases have made this type of research vastly faster and more powerful. A massive database like what the VA is building would allow Hiatt to compare thousands of anonymous medical records with just a few keystrokes.

It would help him and other researchers look for genetic explanations to the mystery of why some people get sick with diseases like lung cancer, and others don't.

"We know smoking leads to lung cancer, but not everyone who smokes gets lung cancer," says Hiatt. "And some people who get lung cancer don't smoke. Is that because of some genetic predisposition? Or some large genetic protective effect?"

Those types of questions are common in epidemiology, as well as in drug development, where researchers try and understand why some drugs work for some people, but not others.

At the VA, one major focus of research is on PTSD, which is relatively common, but hard to predict. Some soldiers suffer terribly. Others don't. To understand why, you need to look for patterns, across large numbers of vets.

Joel Kupersmith, the VA's Chief Research and Development Officer, says the MVP will allow VA researchers to compare the genes of people who have PTSD with others who don't. They’ll also take environmental factors into consideration: Where a vet lives, what other conditions he or she has, what he or she might have been exposed to in the service.

"It gets to be very complicated," says Kupersmith, "and you need large numbers to sort it out."

It's a bit like an impressionist painting that only comes into focus when you stand far away from it. The more data, says UCSF’s Robert Hiatt, the stronger your conclusions.

"Big numbers are important because effects are small. In order to see effects and have some confidence in them, you need large numbers."

Recently, the Million Veteran Project signed on its ten thousandth participant.

The VA's Kupersmith believes that in 18 months they’ll pass the half-million mark. That would put them well ahead of the other medical databases currently available to researchers, including Kaiser Permanete's biobank, which includes anonymous saliva samples -- containing DNA -- from 170,000 Kaiser patients, and is aiming for 500,000 participants.

To reach its goal, VA staff will have to convince hundreds of thousands of veterans to come in and donate blood. They'll also have to reassure them that the information will be kept private.

"The info is totally de-identified," says the VA's Jennifer Hoblyn. "Each sample gets a unique study info number. So actually it won’t be connected with your name whatsoever."

Schuler says he knows this information isn't likely to improve his own health, or even that of the soldiers he served with. But he considers it an extension of his work to help other vets, "another piece of the puzzle," he says.