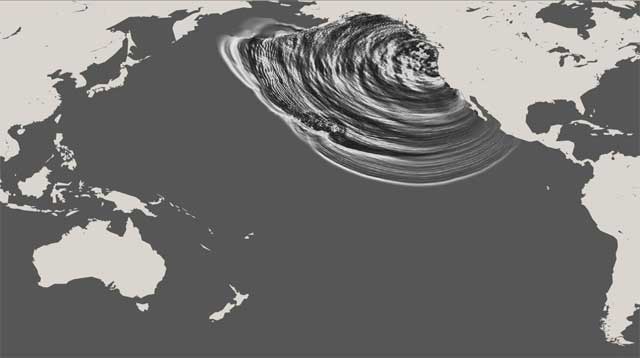

CAMP MURRAY, WASHINGTON- When natural disaster strikes, most of us instinctively run for the hills. But what if you live in the flats, and can't outrun or even out-drive a fast-approaching tsunami wave?

The low-lying coast on the west coast of Washington state is one such region. Residents face both the risk of a major earthquake from the Cascadia fault, and tsunami waves predicted to pummel the shore only 30-40 minutes after the quake. John Schelling, Earthquake Program Manager at the Washington State Emergency Management Division, claims that when a tsunami is approaching, residents need to be prepared to evacuate—vertically.

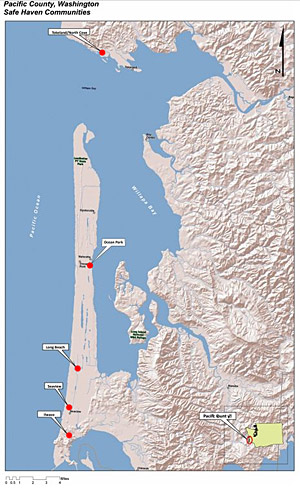

Schelling worked with a team of engineers to plan a series of towers, buildings and berms to provide a vertical escape option that is easily accessible and can withstand the massive force of a tsunami. The proposal, dubbed "Project Safe Haven," is well underway in Washington's coastal communities, including Ocean Shores and Westport where community members have come together to figure out what “heading for higher ground” will look like for them.

“The community members themselves have been the drivers for a lot of the effort that’s gone on in the Safe Haven Project,” says Schelling. “We’ve tried to make sure all of these are multipurpose so that people interact with them on a daily basis.”

But there will be much more physics and engineering going into these buildings than meets the eye.

“The structures themselves have to be designed to withstand at least a magnitude 9 earthquake,” says Schelling. “You’re talking about a significant amount of geotechnical engineering and analysis to make sure the footings that are placed support the weight of the structure, as well as account for the forces that are coming.”