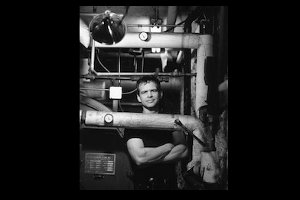

Henry Gifford. Photo by Travis Roozee.

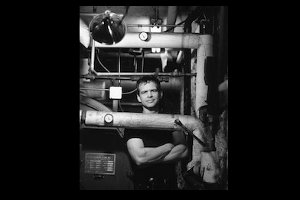

Henry Gifford. Photo by Travis Roozee.

Henry Gifford, a mechanical systems designer and principal at Gifford Fuel Saving, Inc. in New York City, is suing the U.S. Green Building Council (USGBC) for millions of dollars. Gifford, in the class action suit, claims that the USGBC has committed fraud in the selling of its Leadership in Energy Efficient Design (LEED) program, and has unfairly kept work away from people like him who are not involved in the program.

There is a LEED for New Construction (NC), LEED for Homes, and LEED for Existing Buildings (EB), among other certifications. The rub for Gifford is that LEED is a very popular and widespread program—some municipalities require LEED certification for new city buildings—that makes claims about energy efficiency that it can’t back up. The claims of energy saving attract builders and developers to seek LEED certification, and people in architecture firms, building energy consultants, and others in the building industry have rushed to become LEED approved providers; that means they are able to help builders meet the building requirements and fill out the paperwork needed to apply for certification. Buildings with LEED certification draw higher rents and people with “LEED AP” after their names make money shepherding builders through the certification process.

Gifford’s case hinges on the claims for energy savings made by USGBC based on a study the group commissioned in 2008. The New Buildings Institute (NBI) study compared buildings that are LEED certified with similar buildings that are not certified. NBI claims that LEED buildings use about 25-30% less energy than conventional buildings. But according to Gifford, who examined the data from the study, LEED buildings actually use about 29% more energy than conventional buildings. Gifford has legitimate concerns about how NBI gathered, sorted, and analyzed the study data. For example, the data on LEED buildings was submitted by a small percentage of LEED building owners; those who take the trouble to keep records and who want to share information on how their building performs. In another example, the mean energy use of one set of buildings is compared to the median energy use of another set, possibly skewing the results in favor of the LEED buildings.