This is the second of two stories born out of an afternoon at UCSF’s Memory and Aging Center, where a team of scientists, led by Dr. Bruce Miller, is trying to tease out the differences between as many as 200 dementias that affect aging brains.

The two stories have a lot in common: Both introduce us to people who have lived with extremely difficult degenerative diseases: ALS in “Decoding the Emotional Brain,” and frontotemporal dementia in this week’s story. Both open up provocative questions about human nature. And neither would have happened without the generosity of a Northern California family – in this case, Cassandra Shafer, who drove down from Forestville with her daughter, Columbia, to tell me about Cassandra’s husband and Columbia’s father, Keith Jordan.

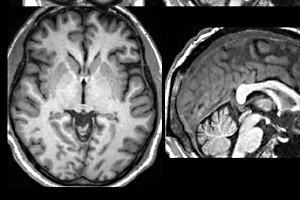

In these video clips, you meet Keith Jordan in the second half of his disease, after doctors at UC Davis and UCSF diagnosed him with frontotemporal dementia. The videos were taken at UCSF over the course of many hours doctors spent studying Keith and his symptoms. In them, we glimpse of two of Keith’s FTD-caused obsessions: joke telling and music. (We also see one of the first symptoms to have emerged: his Jerry Garcia hairdo.)

At first glance, Keith’s behavior might strike you as more eccentric than brain-damaged, which is precisely why FTD can take so long to diagnose. If you’re a doctor with a 15-minute appointment slot, frontotemporal dementia might just look like a midlife crisis. What we don’t see in the video clips are the five heartbreaking years that Cassandra spent trying to figure out what was happening to her husband – a search that included marriage and career counseling, the full gamut of conventional western specialists, yoga, meditation, chelation therapy, replacing every household cleaning product, every pot and pan, all the way to shamanic soul retrieval and exorcism – all while his behavior grew more erratic and difficult to be around. It’s impossible to overstate the drain – both emotional and financial — that this search brought on Keith’s family.