I first heard about synthetic biology several years ago, at a lecture for science writers. The speaker had culled together sections of DNA that he hoped would produce a medically useful enzyme, inserted the sequences into a bacterial genome, then let the bug do its work copying the gene and producing the chemical, which the speaker could then harvest.

This seemed to me to be a fundamentally different way of thinking about biology. Here was a scientist who wasn’t asking: “How does this work?” or “Isn’t the living world amazing?” He was asking: “How can I employ this system to manufacture a specific product for my benefit?” He was harnessing the ingenious mechanisms of biology as tools. Being able to put together sequences of DNA seemed akin to the invention of movable type, a letter here, a letter there, till you spell the words (or in this case, genes) you want.

At some level, I was offended by this, though I’m still not exactly sure why. It seemed like a disrespectful exploitation of life. Who are we to manipulate the code defining living things and make them do our bidding? And how far will we go with this? Will the precious genomes of my plants, or my pets, or even me for Godsakes be manipulated one day, ordered to pump out some substance that a distant researcher has deemed desirable?

On the other hand, I was fascinated. The potential this technique held for research was enough to send a geek’s mind reeling. What amazing ingenuity. What creative thinking. How wholly human, actually, to devise a new purpose for knowledge we’d gained. This engineering feat struck me as demonstrating a deep appreciation—almost a reverence for—the power within the systems that the living world has evolved.

So there I was, conflicted.

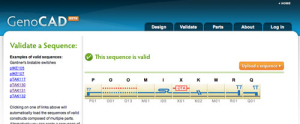

Since then, this process of connecting DNA bits together has become more commonplace. So common, in fact, that a variety of companies, like Gene Design and GenoCad invite you design a gene online and have it sent to you (Go ahead, try it. It’s easy to make up valid sequences.). This is, in fact, what Venter did: ordered sequences of DNA and pieced them together, discovering that he could make an exact copy of the genome he desired.

Synthetic biology’s proponents promise microbes that can clean up pollution, produce drugs, signal changes in the environment, help with medical diagnoses, and a slew of other useful tasks. Its detractors fear the creation of new biological weapons, and new organisms that aren’t well understood but which may be able to reproduce and evolve.

Since this sort of talk makes a sci-fi world of ready-made critters seem like it’s just around the corner, it’s easy to forget how much work remains before our best (or worst) dreams come true. Just because we can string functional bits of DNA together, even whole (though relatively small) genomes, doesn’t mean that we actually know much about how they work. Venter, after all, didn’t invent a new genome, he just put an already-known one together. The goal, of course, is to be able to someday make new genes that do specific things. But for the moment, synthetic biologists hope to use the technologies they’re developing to learn much more about how genes work in the first place.

What does wait for us around the corner is a set of questions similar to those that accompany all new and emerging technologies. How do we create policy to protect ourselves from the risk but not quash research? Who decides what research directions and questions are most important to pursue? How do we create profit incentives for technology that benefits the common good?

And will I ever resolve my mixed feelings about this new science? Is it better off that I don’t?

Robin Marks is a journalist and science writer who current serves as a Multimedia Projects Developer for the Exploratorium in San Francisco, CA.

Robin Marks is a journalist and science writer who current serves as a Multimedia Projects Developer for the Exploratorium in San Francisco, CA.

latitude: 39.1067, longitude: -77.1623

Companies like GenoCAD allow users to piece together

Companies like GenoCAD allow users to piece together