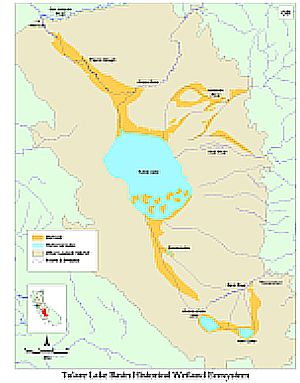

Link to Tulare Lake Map for larger imageOnce upon a time, the San Francisco Bay watershed contained the largest freshwater lake west of the Mississippi. The lake is no more, but sometimes, in wet years, its spirit still haunts the cotton fields that have taken its place. Up until the last century, Tulare Lake was a broad, shallow body of water at the southern end of the San Joaquin Valley. At high water, it was estimated to encompass 790 square miles. Fed by the Kings, Kaweah, Tule, and Kern Rivers from the Sierra Nevada, it was a terminal lake with no natural outlet in dry years. In wetter years, its waters overtopped the basin into the San Joaquin River, from where they flowed northwest to the Delta and into San Francisco Bay.

Link to Tulare Lake Map for larger imageOnce upon a time, the San Francisco Bay watershed contained the largest freshwater lake west of the Mississippi. The lake is no more, but sometimes, in wet years, its spirit still haunts the cotton fields that have taken its place. Up until the last century, Tulare Lake was a broad, shallow body of water at the southern end of the San Joaquin Valley. At high water, it was estimated to encompass 790 square miles. Fed by the Kings, Kaweah, Tule, and Kern Rivers from the Sierra Nevada, it was a terminal lake with no natural outlet in dry years. In wetter years, its waters overtopped the basin into the San Joaquin River, from where they flowed northwest to the Delta and into San Francisco Bay.

The lake was so shallow its annual fluctuations could expose or submerge 100 square miles of land. Even a stiff breeze was said to shift the shoreline several miles. The lake and surrounding marshes (thick with the tules from which the lake drew its name) were rich habitat and a key stop for migrating waterfowl on the Pacific Flyway. Settlers pulled an abundance of fish from the waters (so much that they used it as pigfeed), and the lake's Pacific pond turtles were in demand in San Francisco for terrapin soup. In the wake of the Swamp and Overflowed Lands Act of 1852, change came quickly. By the 1860s, settlers had begun to divert the Kings River for irrigation. The last natural outflow from Tulare Lake seems to have been in 1877. By 1900, the lake had been dried up and its bed claimed for agriculture.

Incredibly, the death of the West's largest freshwater lake was not an anomaly. Similar things took place up and down the Sacramento, San Joaquin, and Tulare basins. Before European settlement, the Central Valley's river floodplain system nourished some 1.4 million acres of tule marshes and wooded wetlands. The draining of vast sweeps of wetlands and the diversion of entire rivers (for agriculture and later, also, for urbanization) has altered the landscape in a manner and at a scale that is, quite literally, unprecedented. Our staff hydrologist has called California's Central Valley and Delta "one of the most transformed landscapes in the world."

And yet, more than a century after its demise, a spectral Tulare Lake still arises during wet periods-- as one writer put it, "like a wet phoenix"--with its most recent reincarnation in 1997. Though there are no plans to restore the lake, there is discussion of restoring some of the benefits it once provided. Already some leveed compartments exist to limit flooding of cropland in high runoff years. Additional wetland areas could further absorb and store floodwaters, while also providing critical habitat and giving some vanishing wetland species at least a ghost of a chance.

![]() Ann Dickinson is Communications Manager for The Bay Institute (www.bay.org), a nonprofit research, education, and advocacy organization dedicated to protecting and restoring San Francisco Bay and its watershed, "from the Sierra to the sea."

Ann Dickinson is Communications Manager for The Bay Institute (www.bay.org), a nonprofit research, education, and advocacy organization dedicated to protecting and restoring San Francisco Bay and its watershed, "from the Sierra to the sea."