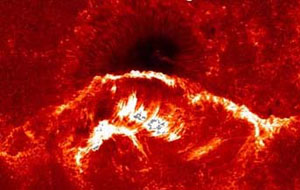

Sunspot 930 (dark area) and associated

Sunspot 930 (dark area) and associated

X-class solar flare of 12/13/06 (bright).

Image Credit: Hinode, Japan Aerospace Exploration

Agency (JAXA).The Sun doesn't usually make the headlines--not even something like, "Flash! Nuclear explosion as powerful as a billion H-bombs sighted only 93 million miles from Earth!"

Let's face it, things like that just don’t seem relevant to our everyday lives. The Sun may be the nearest star, but it still lies at a distance that would take you well over 3000 years to walk, if you could. What happens on the Sun, stays on the Sun, right?

Wrong.

Take Sunspot 930 as an example. Last December, this prominent spot came into view and moved across the Sun's face, carried by the Sun's rotation and marking the location of intense magnetic activity, of which sunspots are a side-effect.

The sunspot itself was equivalent in size to two or three Earths--which is not unusual; the Sun is a big object, and just about everything that goes on there is done in big fashion.

As the magnetic fields twisted and turned, energy built up in them, similar to how tension builds up in a rubber band when you twist it tighter and tighter.