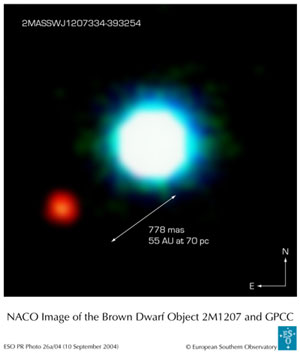

False-colored infrared picture of the first ever

False-colored infrared picture of the first ever

directly imaged exoplanet (fainter) and its parent star

(a brown dwarf—brighter). Credit: European Southern Observatory.

Exo-planet: it sounds like something the starship Enterprise should be visiting-- and though they have been taken for granted in science fiction for a long time, prior to about fifteen years ago the existence of exoplanet-- short for extra-solar planets, or planets orbiting stars other than our Sun-- was only theoretical.

Today, not only are these far-flung worlds a known fact, they’re being turned out in large numbers by astronomers. In 2006, the same year the number of planets in our Solar System went from 9 to 8, the count of planets orbiting stars other than our Sun exceeded 200, and is climbing at a rate of about one per month.

This is exciting stuff, whether you’re mesmerized by the potential of finding life beyond the Earth or simply intrigued by the possibilities of what may be out there in space, given the sheer number of exoplanets in the galaxy implied by observation-- quite probably in the trillions.

The means by which astronomers detect these distant worlds have been mostly through indirect observation-- observation of the effects a planet has on its parent star, whether by the slight "wobble" in a star or the subtle eclipsing of its light caused by the orbiting planet.