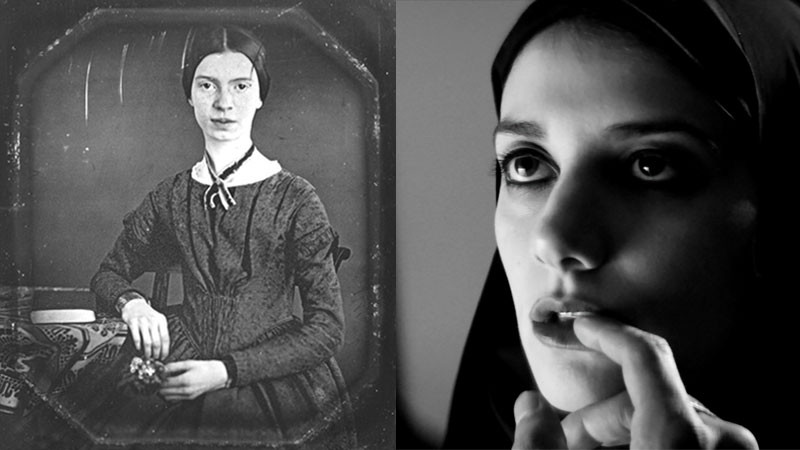

Much has been made of the recent vampire film, A Girl Walks Home Alone At Night, and deservedly so. Nothing in recent memory has illustrated the heart's desires with such style, or with such a killer soundtrack. This is the love story of a feminist skateboarding vampire known as The Girl, and a sweet James Dean-esque boy named Arash, who dresses up like Dracula, but is not a vampire himself.

"Don't worry, I won't hurt you," he says when they bump into each other at night on the street, and the audience I was watching with all chuckled nervously at his obliviousness. When discussing the fact that they don't know each other at all yet, Arash asks The Girl to name the last song she listened to. And who among us has not determined our one true love based on their record collection? The strength of the movie is that each moment offers layers of what it means to connect with one another. The silence, the danger, the intimate spaces are all keenly felt. The Girl and Arash must weigh the risks, the consequences, both of being themselves and of choosing each other.

There is something of a shared sensibility between A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night and Buffalo '66, Vincent Gallo's 1998 film about an ex-con and a ballerina falling love. Both movies have urban landscapes, which serve as desolate backdrops for the flawed lovers who exist there. Prolonged vignettes, often of dancing or singing or silence or staring, create evocative spaces. And it's in these quiet spaces where we can concentrate on what it means to fall in love and why we even do. We are allowed to fully feel the mystery for awhile, if not to be granted any sort of lasting clarity.

A recent Modern Love column detailed the psychological study by Dr. Aron, which examined whether or not intimacy can be "accelerated" by people asking each other a series of 36 questions. These questions culminate in four minutes of looking into each other's eyes, something that happens a lot in A Girl Walks Home Alone At Night. Falling in love has long been considered to be part soul mate destiny, part statistical happenstance. In Dr. Aron's questions and their seemingly magical ability to draw two people together, both fate and pragmatism co-mingle. Partly we want to know each other's fears, and partly we want to sit and watch them flit across each other's faces. Love might be simply creating the space in which to truly see the other person. So much of A Girl... is about this act of looking, what is hidden and revealed within it.

Our vampire girl and non-vampire boy discuss what they do and don't know about each other late at night beside an oil refinery, where he later gifts her a pair of stolen earrings and pierces her ears so she can wear them. They've both done bad things, they admit. But perhaps love is possible, anyway. Dr. Aron's study suggests that a shared sense of vulnerability plays a role in creating intimacy. Arash's vulnerability is of course that he might be eaten alive at any moment, but The Girl's is that she might be discovered for who she really is. These concerns are relatable.